In the lead-up to the Venice Biennale, which opens June 1, we have been digging through our archives to trace Canada’s history at the event. In this instalment, we offer a feature from our Summer 1997 issue in which Peggy Gale looks at Rodney Graham’s presentation at the Canada Pavilion that year.

On the face of it, Rodney Graham’s elegant complex works can be difficult. Each piece relates to others, trails appendages, histories, explanations and references. Every figure of speech has a preliminary story, and so every opening first wants a preamble. This time, we begin in Italy.

There we find the Canadian pavilion for the Venice Bienniale. It is small and irregular, with a large tree growing in a glassed central courtyard. The building nestles among the trees in the Giardini grounds, as if in the shadows or under the protection of its much grander neighbours, the pavilions of France and Great Britain. For years now, Canadian artists have struggled to accommodate their work to the building. Some have even sough alternative sites for their installations.

This year, Rodney Graham represents Canada at the Bienniale. Graham, selected by Loretta Yarlow, Director/Curator of the Art Gallery of York University, chose to work with the pavilion site. His initial plans called for large photographs of Canadian trees to be installed throughout its interior. The photos would be shown upside down, like the images made by a camera obscura, a device in which light passes through a pinhole to project an inverted “live” images into a darkened room. The camera obscura was invented in Italy and is recognized as a precursor of the modern camera. Eighteen years ago, in Abbotsford, B.C., near Vancouver. Graham built one of his own, which he used to generate an image of an inverted tree for an exhibition. The new Biennale project would be a return to that early work. It would connect Vancouver and Venice, Canada and Italy; put our trees amidst their trees.

Those were Graham’s first plans. However, soon after the selection of Graham and Yarlow, Biennale officials considered postponing the exhibition for a year. As a consequence, Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade delayed a formal commitment of funding until the exhibition got the go ahead. It was January before press releases finally appeared, naming Yarlow and Graham as Canada’s official representatives—too late for Graham to travel across Canada to take pictures of anything but bare trees. It was not a good start. Another project had to be conceived.

Graham went to Vanice to have a look. It was still winter and he found the Canadian pavilion boarded up with rough cedar planks, protection against the elements. It gave him an idea.

He asked Biennale officials to leave the hoardings in place. For his new project, the pavilion would look like a rustic hut in a leafy setting. It would be a integral part of a film installation that Graham would construct inside. Like the refuge of a latter-day Robinson Crusoe, the building would become a site that worked both inside and out. And the pearl inside the oyster would be Vexation Island, a nine-minute 35mm film-loop transferred to video laser disc for continuous projection inside the pavilion.

The film was shot in late April in The British Virgin Islands in the West Indies. It opens with a long shot of a small island. We see a man (Graham himself) in eighteenth-century grab; black breeches, red waistcoat and white shirt. He is asleep beneath the tree, a purple bruise prominent on his temple. At the same time, we hear a parrot’s raucous voice insisting that the sleeper wake up. A receding camera shot reveals more and more of the island and then, abruptly, we see the sleeper awaken and stand and shake the palm tree. Absurdly, predictably, a coconut falls to strike the man on the head. When he crumples to the ground, unconscious, the camera once more shows the same small island against the brilliant sky. And so, the film loop begins again.

What fantasies or resolutions are behind this sleeper’s passive façade? Watching the film a second time, of course will be a different experience, because this time we know the ending, or rather, know that there is no ending; that we will return to where we came in; see the same action, rehear the parrot’s admonitions.

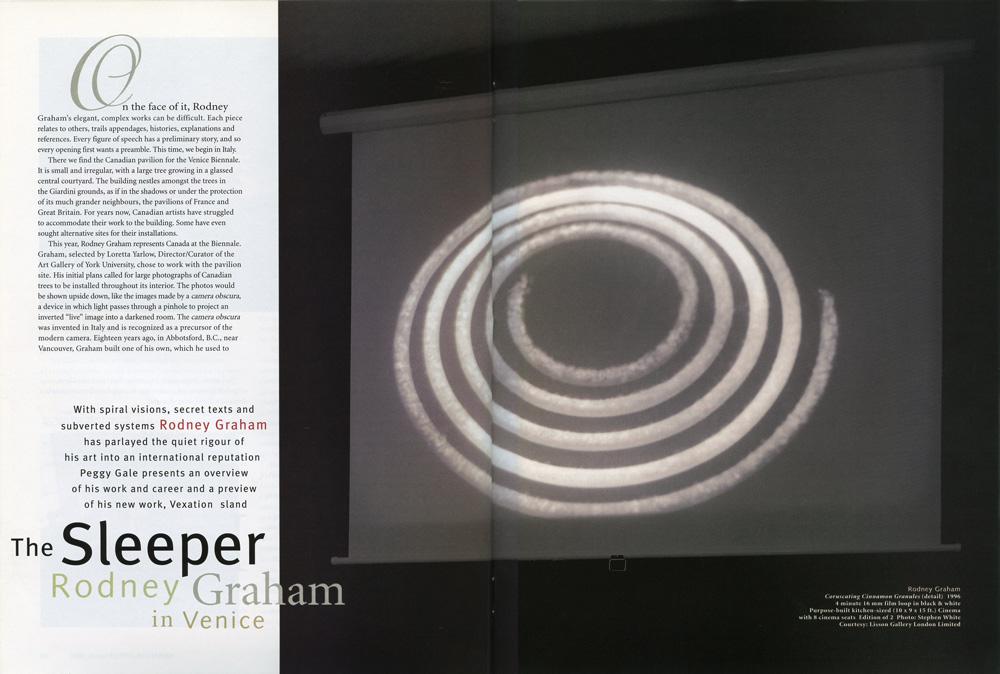

Graham has used film before in his career, and also humour and allusion. In Halcion Sleep, from 1994, Graham recorded himself lying unconcscious in the back of a van, travelling from a motel outside Vancouver to his home in the centre of the city. What could have been the scenario for a kidnapping, or a result of embarrassing excess, was actually a planned performance where Graham first took a strong dose of the sedative Halcion. Viewers only see the artist’s silent, inert form as images of a rain-swept city rush away in the rear window, looking like dream bubbles suspended over Graham’s pyjama–clad body. Coruscating Cinnamon Granules, also 1996, shows and electric stove element sprinkled with cinnamon. As the element is heated to a brilliant glow, the burning cinnamon sparkles like brilliant points of light scattered across a tiny spiral galaxy: a magical image of infinity suggested y the modest means. Graham is a master of this kind of minimal evocative gesture. The unconscious, the dream, the imaginary universe are fertile territory for him, and while his recent films seems but slight things in outline, procedures of distillation and repetition concentrate their effects. Graham’s use of the loop format, for instance, suggests a constant unfolding present rather than a recession into a completed past.

One suspects that for Graham, the past is far from finished. Installations like Parsifal 1882—38,969,364,735 (1991) and School of Velocity (1993) apply calculations and extensions to music by Richard Wagner, Engelbert Humperdinck and Carol Czerny. Interpolations of a different sort have figured in Graham’s text-related projects. In numerous works based on books by Sigmund Freud, Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe and others, Graham has seamlessly inserted new writings into original texts.

The most remarkable example is The System of Landor’s Cottage: A Pendant to Poe’s Last Story (1987), in which Graham added 300 pages of his own invention, and paragraphs from Vathek, penned by eighteenth century writer William Beckford, to Poe’s original short story, turning it into a novel containing an intricate and elaborate sequence of stories within stories. The resulting volume was an opulent construction of vast detail and shimmering splendour. Elegantly designed and printed on 115 gram bouffant paper, the hundreds of uncut pages in the final book offered an invitation to the readers to enter and despoil.

In Dr. No* (1991), Graham, quite differently, inserted a single card, following page fifty-six, in the Ian Fleming paperback. The writing on the card detoured the story into a brief hallucinatory encounter between James Bond and a poisonous centipede, before casually returning to Fleming’s continuing story. Graham’s chameleon eloquence is a marvel. It alters with apparent ease to fit each new circumstance, each verbal and visual style he adopts.

The work is characterized by an obsessive attention to detail. Meticulously researched and exquisitely produced, its quiet authority impresses even before latent and implied meanings are discovered. To seek the generative sources for his art—whether books, sculptures, limited editions, architectural models, music based installations and annotations, even photographs—one enters a dizzying mise en abyme. Yet for all this, one finds a circumspect modesty; it is the work of an educated man.

A fundamental respect for, and dialogue with, both Nature and Culture is apparent in all of it. The former continues to be evoked by Graham’s recurring photographs of massive trees, standing isolated and majestic. For this native of Vancouver, Graham’s trees are particularly appropriate as talismans, serving as a metaphor for the individual in the environment. The seem even more so when one learns that one of Graham’s early years was spent in a lumber-camp in the British Columbia wilderness, and that there, in the evenings, his father projected films in the cookhouse.

As we see nature annotated, framed, imposed on by light, or encase in domestic space, cultural issues being to impinge. The single tree is most often seen inverted, both reflection on the optical process of human vision and acknowledgement of photographic recording devices. Photography provides, as Graham has pointed out, “intermittent illuminations of nature.” A literal example is his Illuminated Ravine, a noisome projection of 1979. In it, Graham lit a open-air setting with harsh commercial spotlights. His related four-minute film, Two Generators (1984), further distances nature from the natural, taking cures from its theatre-viewing context to include the opening and closing of curtains and lights, and through repetition, extending the running time to that of a commercial feature-length movie.

Intellectuality is a constant in Graham’s work, most conspicuously with his play on historical authors and texts. Graham’s considerable output in film, photography, installation, books and sculpture may all be seen as editions. And their variants are second thoughts, or tropes of some kind.

Originally an extra or interpolated passage in the Catholic Mass, the trope has come to indicate figurative language in general. It is a recurring thread for Graham. Everywhere in his work one finds the gloss, the graft, the supplement or appendix. They appear as the veranda, the piazza, the architectural addition or annex, the musical insertion or literary amplification. All are extension or explications. And for the matter, there is projection itself, the flash of illumination, the light of reason.

One should also consider the prominence of dreams in Graham’s work. Sigmund Freud—that coiner of the very term: “unconscious”—appears in his work in many guises. As early as 1986, Graham produced a long wall-mounted sculpture of steel, medite and red lacquer that recalled the reductive formal wall-works of American sculptor Donald Judd. But Graham’s work doubled as a wall-mounted bookshelf holding Freud’s Die Traumdeutung (The Interpretation of Dreams). The following year, for the outdoor sculpture exhibition in Münster, Germany, he placed twenty-four replica copies of Die Guttung Cyclamen (The Species Cyclamen) in downtown bookstores—essentially making a series of windows for the botanical monograph that triggered Freud’s now famous monograph on dreams. In another Judd-like sculpture, done in aluminium and green plexiglass in 1988, he framed the French edition of L’interpretation des rêves. And he has returned to other volumes by Freud for various other sculptural installations, from 1987 to 1993. Then, in 1996, he produced Schema: Complications of Payment, a videotape collection of posters and painting concerned with Freud’s discussion of his difficulties repaying a loan to his mentor, Josef Breuer. Circles and loops spiral ever closer to revelation.

We return to Venice. Vexation Island, with its isolated tree, its supine figure, its whiff of history, shows us the artist as unconscious dupe, caught in a never-ending loop from his own lack of caution or foresight. Innocence and perseverance: knocked out by improvident action. For those with the luxury of choice, sleeping in public is usually reserved for airplanes, or for emergencies. For Rodney Graham, the abandonment of intellect and relinquishing of conscious will offers mystery and promise. A door to the not-yet-known.

The cycle of repetition recalls the oroboros, the mythical snake that consumes its own tail. It is an image of the origin of the world. A figure of speech. Another trope. An opportunity.

Spread from the Summer 1997 issue of Canadian Art

Spread from the Summer 1997 issue of Canadian Art