Note to the reader: Earlier this year, a group of artists, curators and critics from all over the world gathered at the Banff Centre for a summit on Indigenous art. The summit took place during one of the Banff Centre’s Indigenous Visual and Digital Arts Residencies, which welcome creators from all nations to meet with local elders, tap into peer support, and engage in artistic exploration. Here, some of the participants in the summit and residency discuss questions that came up for them during their time at the centre.

Now that we are making a noise, who is listening?

By Candice Hopkins (Carcross/Tagish First Nation, Yukon; Albuquerque, New Mexico

2003 was an important year for Aboriginal art in Canada. Artists, curators, administrators and scholars from across the country, the United States, Australia and Aotearoa-New Zealand gathered at the Banff Centre for Making a Noise!, a symposium on art, art history, community and curatorial practice.

Coinciding with the residency Communion and Other Conversations, the result of a collaboration between curators Lee-Ann Martin, Brenda Croft, Margaret Archuleta and Megan Tamati-Quennell, for many of us this was the first time that the conversations we were having locally—or nationally—were expanded to include the voices of people from other colonial nations. While it was an opportunity to consider shared experiences and histories, what resonated most deeply were the differences, the irreconcilable legacies of the colonial project.

Given the recent rise of international exhibitions of Indigenous art, now is an apt moment “to remember the future,” in the words of my colleague David Garneau. In late January, Garneau and I led a two-day summit in Banff that returned to conversations first raised in Making a Noise!, and posed new questions on what has changed, and what has not, in the more than 10 years since.

Organized to introduce a new and increasingly global network of artists and thinkers to an important history, the 2016 summit brought together invited guests—scholar Jolene Rickard, art historian Richard Hill, artist Raymond Boisjoly, knowledge keeper Tom Crane Bear, professor Ashok Mathur and art historian Dylan Robinson—and international artists from the concurrent Indigenous Visual and Digital Arts residency. It also served as a reorientation for the Banff Centre itself. We often think that institutional memories are long—but they are really only as long as the recollections of people working from within them.

The summit began with a case study by Richard Hill on “Meeting Ground,” his radical reinstallation of the permanent Canadian art collection—and subsequent retelling of the status quo Canadian art narrative—at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2003. “Meeting Ground” did not simply include Indigenous artworks; it ensured that Indigenous histories, artists and ideologies were essential to the exhibition’s design and reception.

New ways to frame these conversations on repatriation were at the heart of the second session: “Our things are not your things, especially if you stole them.” Setting aside the gloss of nostalgia, Rickard sought to expand the discussion of repatriation to include not just museum objects—considered belongings to many Indigenous peoples—but also minds, bodies and territories. Robinson introduced the concept of “hungry listening,” an attempt to recover non-colonial ways of listening, or to listen without intent. Léuli Eshraghi framed the arts institution as a site to repatriate in part due to the little true inclusion of Indigenous curators and museum professionals within galleries and museums in Australia and Aotearoa-New Zealand.

“Will We Ever Be Global?” began with a distinctly Canadian moment in history—the push for greater racial diversity in artist-run centres and the creation and dissolution in the early 1990s of the collective Minquon Panchayat. The collective challenged the white hegemony of artist-run centres resulting in something of an identity crisis in the centres themselves.

Mathur ended with another critical reflection on the present, with a lucid observation on how the Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommendations are in turn producing a reconciliation industry.

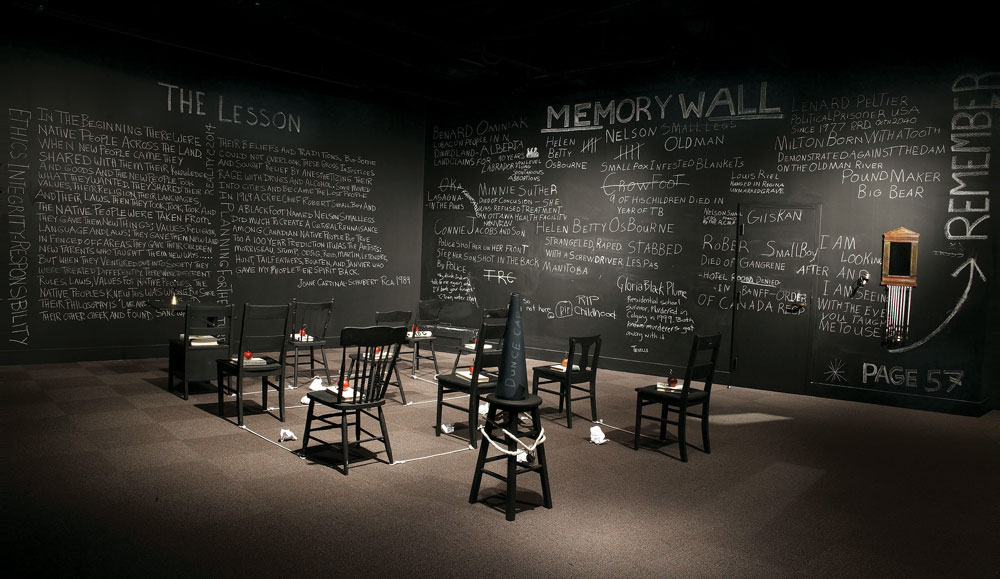

Garneau also began close to home with the practice of the late Joane Cardinal-Schubert. Cardinal-Schubert’s words, which opened Making a Noise!, provide an image of the future of Aboriginal art, whereby artists, curators and art historians are seated (based on “class,” with the artists in business) on a plane piloted by political revolutionary Louis Riel. The destination is unknown, but what is clear is that she intended each of us to author our own futures.

Boisjoly and Kathleen Ash-Milby provided closing thoughts as a way of charting where these conversations are going. For Boisjoly, this includes an interest in how to productively counter miscategorizations of objects that are distanced from their source, how we can make sense of the circulation of Indigenous media and objects. He asked how we can purposefully not satisfy the demand for authority and resist practices (like anthropology) that aim to render us legible. Ash-Milby took the opportunity to present an overview of exhibitions at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, showing how far an institution that initially did not want to show contemporary Native American art has come.

At the end of these two intense days of “remembering” and reckoning, it remained clear that the conversations that began with Making a Noise! are as prescient as ever. In a bid to push that critical momentum forward, to continue to move these conversations into the future, Garneau and I invited a group of summit participants to offer their reflections on the issues raised. The results are not so much statements or declarations as they are reminders, even provocations, to launch further discussion of the unresolved ground ahead of us. They revolve around two key thoughts: how we can think more critically about the economies in which we are working to understand our complicities and, now that we are making a noise, who is listening?

Nicotye Samayualie (right) in her studio during the Indigenous Visual and Digital Arts Residency at the Banff Centre, February 2016. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

Nicotye Samayualie (right) in her studio during the Indigenous Visual and Digital Arts Residency at the Banff Centre, February 2016. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

Who are we really serving?

By Bridget Reweti (Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāi Te Rangi: Te Whanganui ā Tara Wellington, Aotearoa-New Zealand) and Léuli Eshraghi (Sāmoan, Persian; Narrm Melbourne, Australia)

At the opening of the Banff summit, curator and writer Richard Hill discussed his time at the Art Gallery of Ontario in the early 2000s, in particular the institutional opposition toward his 2003 exhibition “Meeting Ground,” which introduced Anishinaabe cultural histories and material practices set among colonial Euro-Canadian landscape works.

Hill’s subsequent resignation from the AGO echoed similar tensions within our own regions. Indigenous art is often seen as expendable when funds are short or will is lacking.

In recent years, the City Gallery Wellington in Aotearoa-New Zealand has chosen not to refill the Māori and Pacific curator position or retain the dedicated exhibition space. Instead the gallery has opted to embed Māori and Pacific artists within a wider curatorial framework.

Similarly, at the National Gallery of Victoria, Australia’s largest public art museum, it has been more than five years since Aboriginal curators were employed. Though a respected Hakö Papua New Guinean curator, Sana Balai, has persevered there for a decade, there are currently no Aboriginal Australian curators in any department. In April 2015, the gallery moved the dedicated Indigenous art galleries from the ground floor to the less visible third floor—without formal consultation or involvement of Indigenous stakeholders—to make way for big-ticket blockbuster exhibitions.

There needs to be a concrete commitment to Indigenous employment and participation for holistic structural change, multiple art histories and diverse cultural practices to be at home in the same public gallery spaces dominated by settler colonial peoples. Representation with one or two Indigenous curators, public programmers or collection managers is not enough. Without support, the obligatory burden of cultural knowledge often leads to “brown” (or whatever other relevant colour) burnout.

Yet there is an ease with which many Indigenous artists and curators establish strong networks and communities, perhaps formed through mutual experiences in sharing the weight of histories. Hill touched on this notion when he encouraged the summit attendees to know our own contradictions. This very understanding of one’s own “cultural capital” brings into light the key question—who are we really serving? And as such, do we really want to be in these existing spaces?

The surrounding dialogue to such answers is complicated but, as Matariki Williams writes, “brown people like art too, and we want to be brown in your gallery.”

Salote Tawale in her studio during the Indigenous Visual and Digital Arts Residency at the Banff Centre, February 2016. Photo: Rita Taylor.

Salote Tawale in her studio during the Indigenous Visual and Digital Arts Residency at the Banff Centre, February 2016. Photo: Rita Taylor.

Can we create sovereign spaces?

By Salote Tawale (Suva, Fiji Islands; Melbourne, Australia) and Suzanne Kite (Oglala Lakota; Los Angeles)

Embodied in each of us is a plurality of contemporary colonial and Indigenous cultures. We draw upon this knowledge as local and global diaspora to disrupt normalized views of our cultures through language, music and visual art. We create works that hold fast to these streams of knowledge that are embodied in our existence as Indigenous peoples, reclaiming and repurposing without the gloss of nostalgia. Our artworks have the ability to create sovereign spaces, places without colonial rule or structures. Not only are these spaces real and imagined, sovereign and unsovereign, but they can function as the “anti,” “de” and “post” of colonial thought in practice.

Focusing the discussion “Our things are not your things, especially if you stole them” on disrupting normalized ways of listening, Dylan Robinson stated that, “Songs are more than just an aesthetic form; they are functional, and do things in the world.” He emphasized non-teleological forms of listening, and introduced the concept of “hungry listening” to identify the differences between settler colonial and various Indigenous forms of listening. From this perspective, the audience is “called to witness” Indigenous art forms as we present them. This “call to witness” our actions disrupts the anthropological colonial gaze, a gaze that believes it should hear, see and acquire everything.

Jolene Rickard made a call for sovereignty, not just in contemporary art institutions, but also as Indigenous peoples reclaiming physical lands and waters. She spoke of the 1779 Sullivan Campaign, its assault and genocide of the Cayuga and Seneca Nations, their consequent dislocation and contemporary moves to return to their homeland. She asked how arts practice can lead us towards sovereignty of our lands and resources, not as romantic places, but as places of action in the present. Rickard’s project, which makes use of geotagging significant Indigenous landmarks, is a means to question our relationship to the ideas defining contemporary art, and how we locate our episteme of knowledge as Indigenous peoples in colonized territories.

Our efforts as contemporary artists, writers and curators are often a negotiation of where the boundaries between “settler logic” and “Indigenous logic” fall. The colonial gaze is hungry, yet establishing these sovereign spaces remains crucial to survival. “Our things are not your things” does not mean contemporary Indigenous art is inaccessible, but that it contains multiplicities of knowledge and holds the past, present and future quite firmly in its grasp.

Tamara Himmelspach (right; with Nicole Kelly Westman) in her studio during the Indigenous Visual and Digital Arts Residency at the Banff Centre, February 2016. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

Tamara Himmelspach (right; with Nicole Kelly Westman) in her studio during the Indigenous Visual and Digital Arts Residency at the Banff Centre, February 2016. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

Are we in or are we out?

By Jackson Polys (Tlingit, Ketchikan, Alaska/New York)

If conversations around the future of Indigeneity are to move beyond a constricting orbit, if they are to go anywhere, we must reckon with contradictions embedded in our aspirations. As Indigenous artists, we hold hopes that remain contested, often incomprehensible to others, even to ourselves. We want to refuse reliance on outside recognition, to have our own spaces, take them back, incubate inside them and continually create them anew. Yet we wish to be recognized: for our contributions to contemporary thought and revaluations of history. We aim to legitimize claims of relevance to those outside ourselves. We remain desirous, envious of inclusion into a mainstream art world and hopeful for influence upon it, while constantly recounting how few our numbers are. We perpetually shift between an exclusive and inclusive “we.”

Seemingly stretched between pursuits of independence and belonging, individuality and community, we face apprehension as to how to leverage strategies of artistic refusal. Raymond Boisjoly, at the summit, implored us to aim for the unknown, and asked how we might set up conditions for the unforeseen “while negotiating in circumstances not produced for our own success.” We must engage in a “necessary dialogue” with representations of ourselves “in order to integrate ourselves into discussion.”

From without and within, expectations persist that to integrate, to court the new, is to risk assimilation. We are up against inherited conceptions of time that impinge on our freedom. Indigeneity always seems to concern a predictable return, thus the difficulty in overcoming doubts about its relevance or currency. Although apparently tied to static, territory-bound concerns, Indigeneity is already at a remove. It implies a position that, according to David Garneau, endeavours toward internationalism and its overwhelming urge to de-territorialize. We might even fear that in identifying as Indigenous we could already be playing into the eliminatory logic of dispossession.

Progress is a notion that encroaches on the future of Indigeneity, as it explicitly and implicitly reproduces coarse divisions between the Indigenous and the contemporary. For Indigenous artists, contradictions inherent to ideas of progress limit the productive potential of a tension between ambitions: to harness the power of a refusal of recognition and to simultaneously increase visibility and relevance. This bleeds into uncertainties as to how to effectively create the new, unexpected or unknown.

And still, crucial questions remain: how can we articulate success through other terms, and, as Kathleen Ash-Milby put it, “what are we going to define as success for ourselves?”

This article is adapted from a feature in the Summer 2016 issue of Canadian Art. To get each issue of our magazine delivered to your door before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.