During the long and successful career that ended with her death in December, the Canadian-born artist Agnes Martin was variously called “the ascetic high priestess of Minimalist painting,” a “mystic,” a creator of “visual epiphanies.” Her paintings were likened to prayers.

Extravagant, religiose language of this kind always comes dangerously close to bad taste, and illuminates neither the art nor the artist who makes it. But such straining for apt words reflects the real difficulty that critics felt—I count myself among them—when called upon to account for what, exactly, made us admire and even love Martin’s paintings.

What she did was famously spare, open-handed and uncomplicated in its facture, and that made it easy to talk about. Her official place in the art-history books, among the Minimalists—though she always identified more strongly with the Abstract Expressionists—was quickly and firmly established. For those who tracked the trends, her painting’s simple, regular forms epitomized the plain dealing, and the renunciation of Abstract Expressionism’s turbulence and incident, of the mid-1960s Minimalist moment in New York painting.

But if it was clear what her art was, it was always harder to say what it was about—because we did not really believe her when she said it was about perfection. It had to be more complicated than that.

It was not.

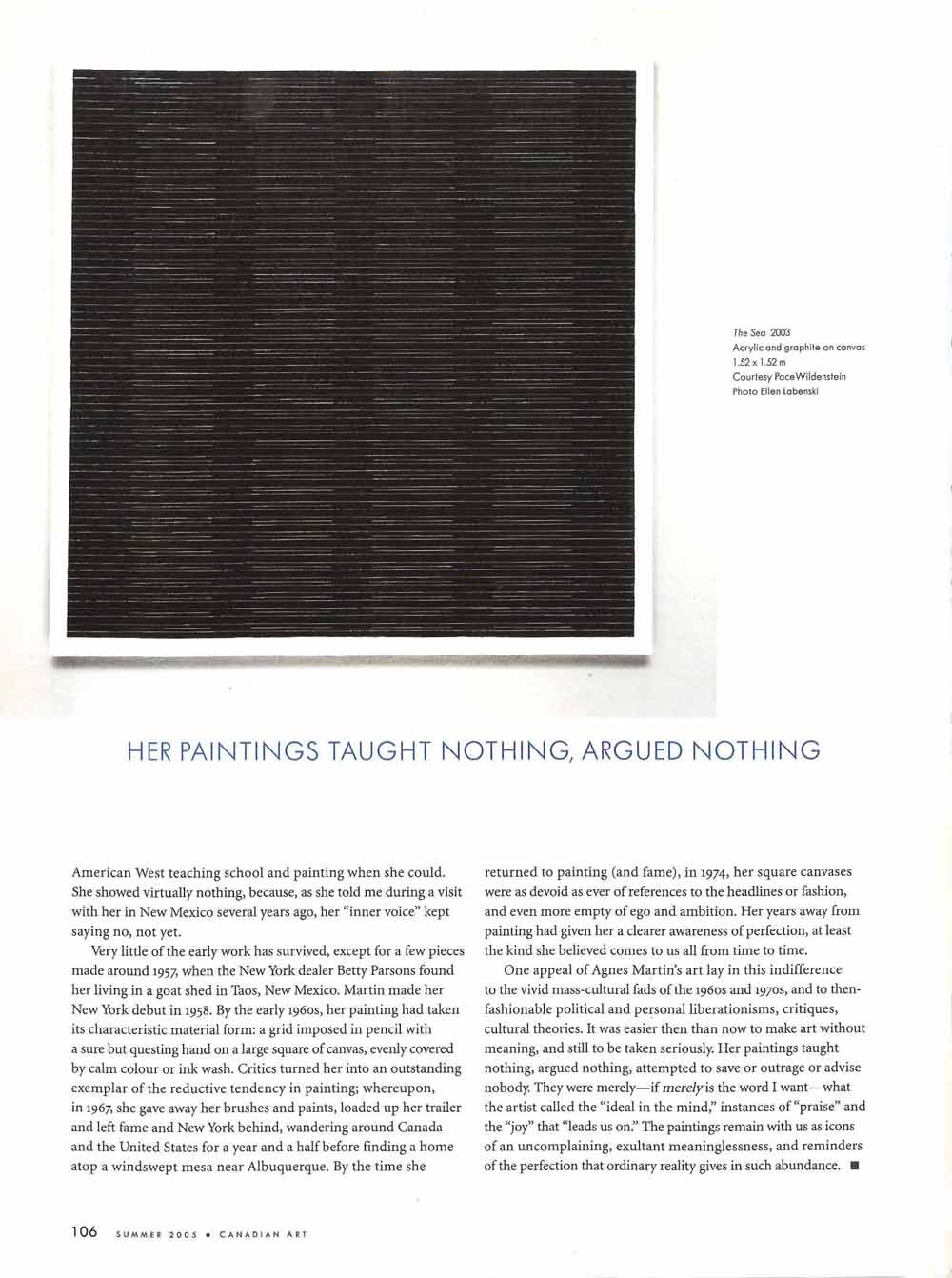

With the passions of a folk painter—resignation, a fondness for repose, recollection and the simple life, patience, a dedication to minding one’s own business—she sought to give visual presence to the sense of perfection, or completeness, we all experience at one time or another. When asked what her painting was about, she liked to say it was the perfect peace of being on a beach, looking at the ocean. There is nothing mystical or transcendental about it, as there was nothing mystical about her.

Agnes Martin had a kind of simplicity, a simple, steady grasp of what’s important in life that the hurried world needs very badly. “In my best moments,” she wrote, “I think Life has passed me by and I am content.” At some point, sooner or later, we must all come to such a good moment—by the sea, or merely in the quietness of our room—or remain forever nagged and made unhappy by the hungry ghosts of desire.

Like most other people, Agnes Martin enjoyed a few of these good moments, and endured many more ordinary ones, which leaves us without a very exciting story to tell about her life. She was born in 1912 in Maklin, Saskatchewan, to Scottish immigrant farmers, and never married. She left Canada early, to become an elementary-school teacher in Washington state. She came to art quietly, while studying in New York during the Second World War, and she spent several years back in the American West teaching school and painting when she could. She showed virtually nothing, because, as she told me during a visit with her in New Mexico several years ago, her “inner voice” kept saying no, not yet.

Very little of the early work has survived, except for a few pieces made around 1957, when the New York dealer Betty Parsons found her living in a goat shed in Taos, New Mexico. Martin made her New York debut in 1958. By the early 1960s, her painting had taken its characteristic material form: a grid imposed in pencil with a sure but questing hand on a large square of canvas, evenly covered by calm colour or ink wash. Critics turned her into an outstanding exemplar of the reductive tendency in painting; whereupon, in 1967, she gave away her brushes and paints, loaded up her trailer and left fame and New York behind, wandering around Canada and the United States for a year and a half before finding a home atop a windswept mesa near Albuquerque. By the time she returned to painting (and fame), in 1974, her square canvases were as devoid as ever of references to the headlines or fashion, and even more empty of ego and ambition. Her years away from painting had given her a clearer awareness of perfection, at least the kind she believed comes to us all from time to time.

One appeal of Agnes Martin’s art lay in this indifference to the vivid mass-cultural fads of the 1960s and 1970s, and to then-fashionable political and personal liberationisms, critiques, cultural theories. It was easier then than now to make art without meaning, and still to be taken seriously. Her paintings taught nothing, argued nothing, attempted to save or outrage or advise nobody. They were merely—if merely is the word I want—what the artist called the “ideal in the mind,” instances of “praise” and the “joy” that “leads us on.” The paintings remain with us as icons of an uncomplaining, exultant meaninglessness, and reminders of the perfection that ordinary reality gives in such abundance.

This is a feature from the Summer 2005 issue of Canadian Art.