Palestinian-Canadian artist Rehab Nazzal’s exhibition “Invisible” closed on June 22 at the end of a one-and-a-half-month run at the Karsh-Masson Gallery, located in Ottawa’s City Hall. The show sparked attacks from conservative politicians in the Senate and the House of Commons after Israeli ambassador Rafael Barak complained about it to Ottawa Mayor Jim Watson, and the Jewish Federation of Ottawa issued a statement condemning the exhibition and calling for its removal.

To its credit, the city (which operates the gallery at arm’s length as part of its public art program) resisted pressure to shut the show down early. However, according to a CBC report, Mayor Watson ordered a review of the exhibition selection process. At present, an independent, three-member jury chooses exhibitions. It is too early to know what the results of the review will be.

It was at this point where people began to respond publicly that “Invisible” began to realize its full political potentiality, until then latent in the work Nazzal had created. Entering the public realm as it did, it became what art historian Reesa Greenberg has termed a “discursive event.” It is this aspect of the exhibition that I intend to address here in addition to discussing the works themselves. As Greenberg observes, “When an exhibition is framed as a discursive event, its success is not as dependent on traditional aesthetic criteria. Judgments of the good, the bad, and the ugly are less applicable. What matters more is how much discussion is generated, for how long, in which sectors of society and, most importantly, to what effect. The emphases become ethics rather than aesthetics, practice rather than theory, audience rather than artist.”

One work in particular acted as a catalyst for the exhibition’s opponents: a four-minute video entitled Target (2012). I will return to it later in more detail. For now what is important to observe is the way in which it was isolated and used to condemn the exhibition as a whole. Target was one of four short videos that—along with a large, composite photographic work comprised of some 1,700 stills—made up the exhibition. The artist chose not to provide background information or interpretive explanations with the works exhibited. Individually, the works formed the strands of a larger narrative by virtue of their inconclusive, fragmentary character. While Nazzal’s exhibition title offered an overarching metaphor, drawing attention to what remains invisible behind the rhetoric of the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict, she deliberately left the strands to be united by the viewer.

The immersive darkness of the exhibition space, punctuated by the flickering video screens and the staccato sounds of cries and shouts from one work positioned at the back of the gallery, behind a wall that blocked it initially from sight, focussed the viewer’s attention on what is seen and what is unseen as well as on what is heard and unheard. Nazzal used sound in alternation with silence strategically.

The centrepiece of the Nazzal’s show consisted of two interconnected works.

The first of these works, Military Exercise in the Negev Prison (2013–2014), is a seven-minute video based on material recorded during a 2007 military exercise in the notorious detention facility, also widely known as the Ketziot (or Ktzi’ot) Prison. At this facility, Palestinian prisoners can be held in Israeli custody indefinitely in administrative detention. Nazzal’s video separates the sound and images of its documentary source—it is all sound, with the only image component being the translated transcript of the exchanges between the soldiers and the prisoners running across a black screen.

For the second of these works, Frames from the Negev Prison (2013–2014), Nazzal isolated images from the video footage of the military exercise, which was a surprise search of the prison that took place in the middle of the night and resulted in one prisoner dead and dozens injured. These photographs she fashioned into a mosaic of images punctuated by black squares.

It is important to note, as part of the context of these works, that the original Negev Prison video, kept secret by the military, was finally released in redacted form in 2011 and aired as part of an Israeli television documentary examining human rights abuses at the prison. The history of this episode demonstrates that much of what goes on in such prisons is invisible to the outside world. According to Wikipedia, members of Human Rights Watch visited the prison in 1990 and reported numerous abuses; the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem confirmed their findings after visits in 1991 and 1992. No visits by the group have been allowed since. The black squares interrupting the images in Nazzal’s photo piece act as a metaphor for this protective secrecy.

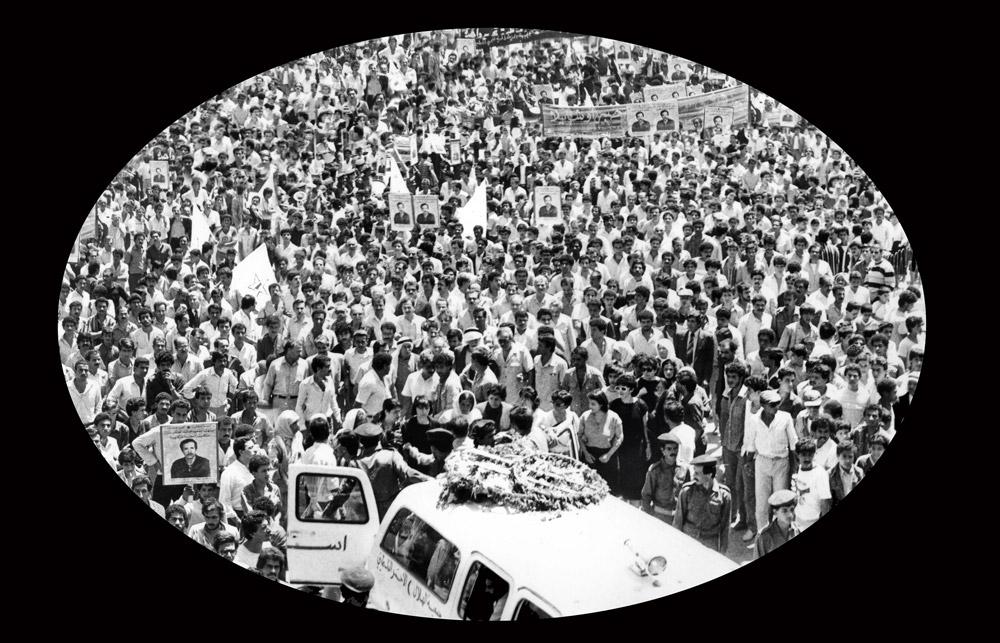

In contrast to the Negev Prison video, the first work the viewer encountered on entering the gallery was a soundless video entitled Mourning (2012), which portrays a massive crowd gathered for what I later learned was the funeral of Nazzal’s brother. The mourners weep and cry out before our eyes, but remain unheard. Nearby, Target, which records the faces, names and details of the deaths of Palestinians murdered in execution-style attacks, is also silent. In the last video, Bil’in (2010), filmed by the artist during one of the weekly protests in this West Bank village, the sounds, up close and intimate, are intact but the images are obscured to suggest tear-gas blindness.

Nazzal is wary of the limitations of documentary modes of representation in a situation she and those close to her have lived from the inside. She uses a variety of formal strategies to restructure and transform her source material, which includes found footage, archival documents and her own films and photographs.

For instance, the most contested work in the show, Target, is composed of images of posters she has recorded in Palestinian streets and of found portraits of Palestinian leaders, intellectuals, and activists murdered by Israeli forces both inside Palestine and in other parts of the world. The images, isolated as if framed through a rifle sight, emerge and fade into the background too quickly to be easily deciphered. They fall in an obscure pile, as if to emphasize the number of summary executions carried out over the course of the long conflict, rather than the individual identities of the fallen.

Though Target seems to suggest a sense of mass and an obscuring of individual identity, it is precisely the individual identities in it that have mattered most to its harshest critics. Such voices accuse Nazzal, through her depictions in this video work, of “celebrating terrorism.” In her Senate speech decrying the mayor and city councillors of Ottawa as “enablers of hate,” Linda Frum listed some of the people in the video—including Nazzal’s brother, who was killed on the streets of Athens—and then offered a counter-list of Israeli victims.

Yet victims on both sides, mourned by their families, are the tragic fruit of war. As Michelle Weinroth writes in a Rabble article defending Nazzal’s work and her right to exhibit it, “How we define and judge the agents of war largely depends on our point of view. Resistance fighters are deemed martyr heroes on one side, but terrorists on the other.”

But Frum didn’t just want to draw Israeli victims to our attention. She told her listeners, “I know I speak on behalf of all decent and peace-loving Canadians who abhor terror as a means to obtain political ends. For the citizens of Ottawa, this exhibit is a particular travesty since their tax dollars are being used to glorify the murder of innocent civilians.” Frum finished by stating that the exhibition did not represent “the real Canada.” Shifting attention from the conflict in Palestine, which has its historical roots in the expulsion of 800,000 Palestinians from the new state of Israel in 1948, to Canada, Frum mounts an attack on our right even to view an exhibition that is critical of Israel. Yet the Negev Prison events, which she ignores, were condemned on Israeli television in a program addressed to Hebrew-speaking Israeli viewers.

Nazzal’s critics do not simply oppose the viewpoint depicted in her work; they oppose its right to be seen. In her reply to the the attacks on her exhibition, published in the Ottawa Citizen, Rehab Nazzal responds: “My art, including this exhibition, is informed by my own experience and life under the Israeli occupation. The questions raised by the works in Invisible are challenging, but they are part of the tradition of critical art. It is through challenging interventions that suppressed subjects can be brought to light. The extra-judicial assassination of Palestinians, the attacks on peaceful Palestinian demonstrations, and the brutal treatment of Palestinian prisoners, these are the central issues raised by the various works in the exhibit.”

As a discursive event, “Invisible” offered an opportunity for observers to identify and engage with the issues it raised. And because it happened in public, we were prompted to examine what we mean when we talk about public space. In the aftermath of the Second World War, Hannah Arendt offered an exemplary definition of the public sphere in her book The Human Condition. There she writes, “The reality of the public realm relies on the simultaneous presence of innumerable perspectives and aspects in which the common world presents itself and for which no common measurement or denominator can ever be devised. . . . Being seen and being heard by others derive their significance from the fact that everyone sees and hears from a different position. This is the meaning of public life . . .”

Arendt’s words serve to remind us that the spaces we have in common—both physical space and the space of public discourse—are spaces marked by difference. When we acknowledge that each of us has a right to participate in this space within certain agreed-upon civic parameters, rather than seeking to exclude by invoking notions of privilege or ownership, we show an understanding of public space that makes it democratic space.

But the reception of Rehab Nazzal’s exhibition—a reaction which was markedly different from past presentations of Target and other works at IMA Gallery in Toronto and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, presentations which generated little controversy at all—was complicated by the nature of the space in which it was located. The architecture of Ottawa’s City Hall provides a shared public space in the form of an open concourse that stretches from one end to the other of the building. Opening onto this concourse are various spaces that do not pertain directly to city business and whose activities are not governed by its transactions. In addition to areas like that devoted to the skater Barbara Ann Scott, which are clearly meant to evoke shared civic pride, there are others, such as the Karsh-Masson Gallery, whose mandate is to “increase awareness of the visual arts and the heritage of Ottawa.” Its space is regularly turned over to contemporary artists to express their individual concerns, without any prescriptive criteria other than the pertinence and quality of their work.

The open-ended indeterminacy of the Karsh-Masson’s process, characteristic of public space, combined with the gallery’s proximity to civic governmental functions, creates an ambiguity that certainly contributed to the polarized reaction to Nazzal’s exhibition. Had the exhibition been held at nearby SAW Gallery, an artist-run centre, it is unlikely to have provoked the same controversy. As it is, the exhibition has become an event that tests our democratic understanding of public space and of art’s public role.

The question has been visited before and is worth reviewing here. The 1982 Applebaum-Hébert Report, for instance, offered this view of the distinction between the role of government and the role of art: “Government serves the social need for order, predictability and control—seeking consensus, establishing norms, and offering uniformity of treatment. Cultural activity, by contrast, thrives on spontaneity and accepts diversity, discord and dissent as natural conditions—and withers if it is legislated or directed…. The cultural sphere, embracing as it does artistic and intellectual activity, has as one of its central functions the critical scrutiny of all other spheres including the political. On this score it cannot be subordinated to the others.”

Nazzal is right to insist on the place of her work within the tradition of critical art. But her critics demonstrate by their attacks that they make no distinction between art and other forms of public speech. Although her work does not advocate violence, it is portrayed as hate speech. Michelle Weinroth, cited above, describes the true function of engaged art with feeling and accuracy: “War binds the defeated to the recollection of unspeakable tragedy, so unspeakable that it is often silenced by public discourse. Still, in spite of such suppression, collective memory resurfaces in the interstices of aesthetic culture. In art and music, in theatre and dance, the story of war’s victims is revived.”

The headline of Weinroth’s Rabble article describes Nazzal’s exhibition as “under siege.” Yet alongside the political attacks, the exhibition also generated much sympathetic commentary—frequently in the form of online posts that took issue with the simplistic character of the arguments calling for its closure. Although the debate was less nuanced than it could have been, it offered a vivid demonstration of the diversity of opinion that characterizes the exhibition as discursive event.

“Invisible” and its responses were also a test at the civic level of the political will to withstand influential opposition, including attacks on an artist’s right of freedom of expression. Recently in conversation, Reesa Greenberg recalled to me an idea that curator Charles Esche brought forward in the symposium Questions to the Museum of the 21st Century, held at the Van Abbe Museum in Eindhoven in 2011—namely, that art is a minority culture and it is the function of a democracy to protect its minorities.

From this perspective, the mayor and the city managers responsible for the public art program behaved with exemplary integrity. In a letter to the Jewish Federation of Ottawa, Mayor Watson wrote that in more than 20 years of hosting independently juried exhibits, the city has never shut one down. The city should be encouraged to continue its protection of art’s place in the public realm.