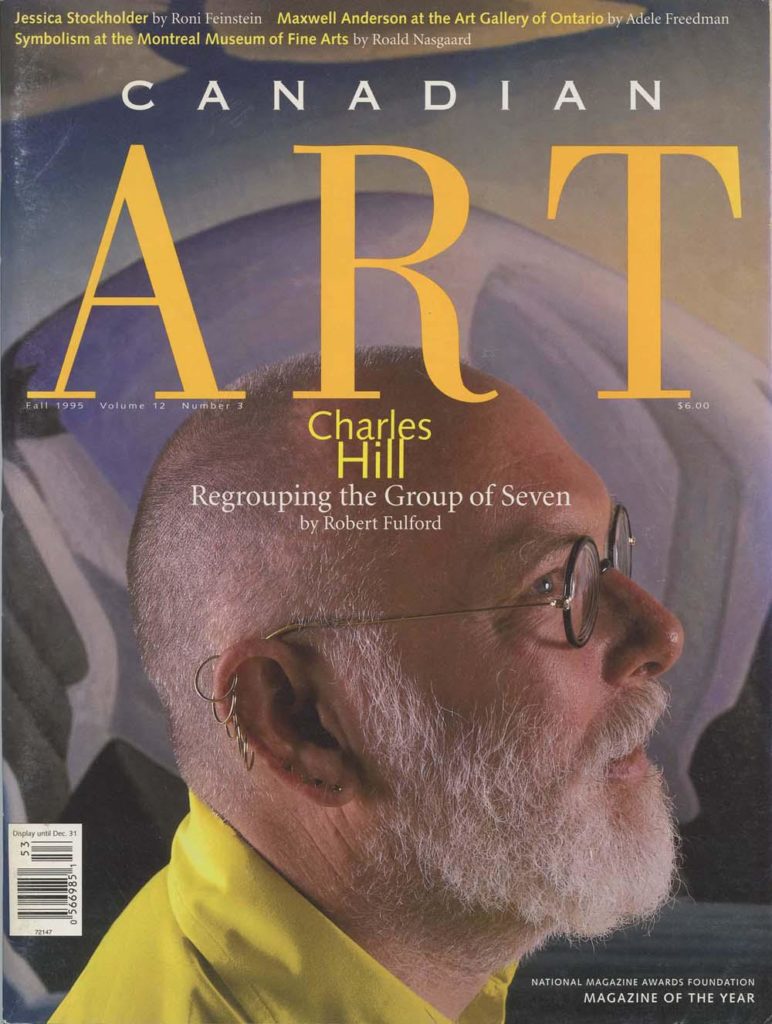

It would be evasive to start with anything but Charles Hill’s earrings. They are, after all, what everyone notices first about him, and beyond question they signify a great deal. They make a statement, these ornaments: they are not ordinary earrings. They are specifically the earrings of a scholar who draws fine distinctions, a curator whose working life is dedicated to imposing order on chaotic reality, the sort of earrings Carolus Linnaeus might have worn if, in eighteenth-century Sweden, the father of scientific classification had thought to wear earrings.

As disciplined as elite troops, they march down the right side of Charles Hill’s head, beginning just below his carefully cropped white hair. First come the earrings proper, five of them, handsome gold loops, swinging outward from the ear’s helix in graceful arcs. Just beneath them, in a straight descending line, are three small, precise, triangular studs. Finally, toward the bottom of the lobe, as punctuation, there is a single ruby stud, a circle, the period that ends a highly expressive sentence. In all there are nine objects on the right ear, but the left holds slightly fewer, as if to suggest that their owner, no slave to convention, eschews formalist symmetry. Then, of course, there are the tattoos—careful tattoos on his arms, nothing flagrant, nothing excessive. The right arm displays plain bands in varying widths, suggesting a painting Kenneth Noland might have made if had decided to have a black-and-white period around 1970. Sleeves rolled up, ready for work, the fifty-year-old curator of Canadian art places his tattoo firmly on his desk at the National Gallery in Ottawa as he explains the rescue of history.

So begins our Fall 1995 cover story. To keep reading, view a PDF of the entire article.