Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore is one of Canada’s most widely respected creators—and for good reason. For one of her most recent installations, unveiled in Athens in April and widely admired by the international press, she sculpted a small refugee tent out of marble and placed it on a hill facing the Parthenon.

Closer to home in 2014, Belmore dug up mud and clay from Manitoba’s Red River Valley and worked with people in Winnipeg’s Indigenous communities to shape that clay into a large, beaded blanket for the opening of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. And in 2002—well before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission or Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women—Belmore performed Vigil on a street corner in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, yelling out the names of missing women one by one and paying homage to their lives through visceral, powerful gestures.

But for all her renown, and vast range of work, Belmore is perhaps most widely known for a piece she launched in Banff in 1991, and then toured through Canada—Ayum-ee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to Their Mother. For it, Belmore built a huge wooden “megaphone” and invited members of the public to speak into it, amplifying their wishes to the land. In Belmore’s words, “asking people to address the land directly was an attempt to hear political protest as poetic action.”

Now, in Belmore’s newest body of work titled Wave Sound—to be unveiled in three locations across Canada this month as part of LandMarks/Repères2017—the artist seems to invert the strategy she made iconic in Speaking to Their Mother. That is, instead of gesturing towards the power and politics of speaking to the land, Wave Sound invites members of the public to actively listen to the land through objects specially designed by the artist.

Here, Rebecca Belmore speaks with Canadian Art’s Indigenous editor-at-large Lindsay Nixon about Speaking to Their Mother, Wave Sound, and the need for all of us to get just as good at listening as we might be at speaking.

Lindsay Nixon: I wanted to talk first about how your work for LandMarks 2017 is sort of the inverse to Speaking to Their Mother. So, instead of speaking to the land, we’re listening to the land this time. I was wondering why this was so important to you to return to now, 26 years later.

Rebecca Belmore: Well, it started with the conversations that I had with curator Kathleen Ritter. I know that she was interested in working with me because of my earlier work, and how she felt it connected to the LandMarks theme and the ideas behind each undertaking.

So I thought about it, and we talked about Banff being perhaps one of the sites that we would select, one of the parks we’d select. Of course, that made me think about the megaphone, or Speaking to Their Mother.

I didn’t really want to remake that work—we could have even taken it again, right? So, I thought, “What am I going to do?” I went back to the ’90s—thinking about that time and then fast-forwarding to today. I thought that maybe listening, making listening devices using a similar cone shape, made sense.

Because when I think back to the early ’90s, I wanted people to speak directly to the land. The way that work functioned, when it functioned well, was when it would find an echo, so your voice would echo back. You’d kind of be confronted with your own self in relation to the land, you know? It’s this relationship between the land and yourself.

This new work is similar. They are very connected, but are told from a different vantage point.

LN: The Oka crisis was happening around the time of the first install. Were there any such events that inspired you to make this piece during this time?

RB: Absolutely. I wouldn’t say it was a direct kind of knowing, but I think when I was taking the megaphone across Canada in 1992, which was 500 years since Columbus, is that what we were celebrating, or “de-celebrating” at the time.

Taking it to First Nations communities on reserves, rural as well as urban, was really interesting. When someone spoke through that megaphone, people would generally sit well in front, and face away from the object, which I thought was really quite beautiful. The art object itself was simply a tool, and people weren’t actually looking at it; they were looking out to the land, and the urban landscape.

In a sense, this current project is similar in that the objects will function as listening devices. It’s more about nature and the human body, and the art object is just the means to have a physical experience.

LN: You’re returning to Banff again with Wave Sound. Was this intentional? Did you want to facilitate a reciprocal dialogue?

RB: Absolutely. It made sense to revisit that place, because I’m rethinking or relating the work on some level. I’m excited about seeing what the difference might be. I’m hoping that people will engage and use the piece while it’s out in the park.

LN: How do you see kinship teachings and relationships to the land as flowing through and informing this work?

RB: Well, based on my own experience as Anishinaabe, I would say that for me, growing up in Northwestern Ontario and spending every summer until I was 16 with my mother’s parents, my grandparents. Just spending summers watching my grandmother basically harvest the land for our food, and doing it quietly, just as an everyday kind of beautiful thing.

I don’t speak our language, and she didn’t speak English, so for us, it really was just about relating through trust, and being with her out on the land. I cherished those childhood summers. They were amazing.

In terms of kinship, this work will be based on a rock or on the land, so you have to crouch. You’ll put your ear to the object and hopefully you’ll hear something beautiful. I think it’s really about taking a moment to sit on the earth itself. That’s really what I’m after in terms of this idea that as human beings we are connected to the earth. It’s pretty simple, but I know it’s huge.

LN: You modelled the new objects after rock formations on the earth’s surface. What inspired you about those forms?

RB: I can’t really trace it to a moment; it just happened gradually. I was trying to think about LandMarks and these parks and what the intent of this big project is—trying to figure out how to deal with such a vast land. Starting in Banff made sense and then going home to Lake Superior on the north shore, then going way far out east.

I was thinking about the vastness of the land itself, and how to make a work that could be strewn across such a great distance. This led me to think about the rock on the earth, and it made sense to take an impression of that surface—of the land, of that ancient, ancient land—and try to in some way put it into the work, so that it would physically become part of the work

It does feel kind of obnoxious to make objects that will then be placed out in nature. I did struggle with it, to be honest. This is how I solved my problem: to insert an object, an artwork, into the landscape is pretty challenging and humbling, and I had to figure out how to do that in a respectful way.

LN: Since you brought it up, what does it feel like to bring this work back to your home territories?

RB: I went with Kathleen for a site visit early on and I returned later with my husband and my brother, and we had a beautiful time being there. I enjoyed being there because Lake Superior is such a phenomenal body of water.

I spent my teenage years and my early 20s in the city of Thunder Bay, so I’m familiar with Lake Superior and how amazingly powerful it is as a great lake. And I was excited about bringing the work to Pukaskwa Park to listen to Lake Superior. I haven’t lived in that area for a while, but I visit all the time and I have family there, so I’m happy about going back to an earlier time and taking something back home.

LN: That’s beautiful. When we’re talking about Indigenous relationships to land, in correlation to your work we have to talk about terra nullius and the association of land with Indigenous women’s bodies. Does this re-centering of listening to the land have anything to do with a reification of women’s knowledges and their connection to the land?

RB: Maybe not on an overt level to people who would encounter the work. I made it for the public, the average person who comes to the park. It really was about the idea of the individual, whatever their relationship is to this place, or whatever they think about their relationship to the earth itself, especially to the water.

For me, on a personal level, it goes back to being with my grandmother and us being children, and being outside and living outside during the summer and watching her, and knowing that she had a different way of being with the land. I carry those memories and that knowledge and that witnessing, from my own experience, and it does filter its way into my work—maybe without me being conscious of it. I am the way I am because of how I grew up in this world.

Of course, I do think about what has happened to us on our own land, but that’s a whole other huge story. Here, I think I’m just trying to sit people down: to ask people to sit on the rock and take a moment and just listen, to experience whatever they hear and to think about their own experience.

In some way, this work, even though it’s a public artwork, that’s placed in the amazing land, or landscape—it’s placed out on the most beautiful spots—I think that when one sits and listens, you cannot help but think about all kinds of things.

For me, as an Indigenous woman and as an Anishinaabe woman, I have my own experience of how I feel about how I relate to this land, and especially, for sure, Northwestern Ontario.

LN: One of my own writing idols, Leanne Simpson, integrates your artworks into her poetry. And she has described your work to me in a recent interview as something that is not seen; it is experienced and felt. And I was wondering, why is affect such an important part of your practice? Is this intentional? Or is it just something that comes naturally from your own practice?

RB: It comes naturally from my own practice and probably my own experience. I go back to being Anishinaabe and being a non-speaker of the language. I understand a little bit, but I didn’t grow up being taught, and there’s the whole story of how that came about. But I think for me, somehow, there’s the time that I’ve spent with my kokum, and it’s a weird thing, this whole thing of conveying this rupture of our languages. It’s much talked about, and it’s a big deal right now, but I don’t know if it’s still fully understood.

What I guess I’m trying to get at is: I have a strange relationship with language. I’m sure many people have the same experience—you develop a way of communicating without the spoken word, with the body.

I think those things are really important to me, and I think that’s how, perhaps, I gravitated towards making works that are more performative, or where the body is implicated in the work itself. I think the megaphone piece of the early ’90s is a good example of that; it’s the body and the voice that activates the work.

And in this [newer] work, it’s the body and the ability to listen—to listen well, and experience not what we think is the “quiet,” but what is the world outside of our bodies. Moreover, it’s about listening to the water and the land and all the other beings that live out there, too.

I think it’s really important to me, in this time that we are living, to be aware and concerned about the future of our own people, and the future of others, as well. We have to somehow work together to have a future for the children that are running around right now. It’s such a huge conversation, and I think it’s difficult to listen.

So perhaps I’m just trying to get the individual who comes across the sculpture on the land to take a moment to listen. I have no idea what it’s going to sound like, but I can’t help but think it’s going to sound amazing. But I have no idea, so, we will see.

LN: This is such a weird question, but you must know that a never-ending chain of Indigenous women are so inspired by and motivated by your work. Have you ever thought about that chain of connection with those people who you inspire?

RB: Not really; I don’t. But that’s good, I think that’s how we function—you have people who are older than you and they are ahead of you and they’re going forward in a certain period of time, in a certain time and place, and as time trudges forward, other younger people are behind you, and their experience will be different.

The world will be a different place in 20 years, and I have no idea what that looks like. So I think that’s why we have to have conversations, that’s why you have to listen, that’s why we have to make art. I admire people who have worked before me. So there is a connection and a moving forward.

LN: You worked with your partner to make these new sculptures, and I was wondering, is creative collaboration and that kind of care part of your whole practice? Why was it important for you for this work?

RB: Well, my partner Osvaldo [Yero], he’s an artist himself, he’s in sculpture, and he is a part of my everyday, 24/7. I think he definitely was key to helping me with this project because his skills as a sculptor are much more sophisticated than mine. He’s a maker of things, and I truly appreciate his expertise and I trust his way of doing things. So I wish to acknowledge him on this project.

He was actually the one who, when we went out to the sites at the parks, was the one who had the knowledge and the skill to make a cast of the actual rock surface, which then became part of the piece. He’s a big part of this project, as he is with many, many things. I totally trust his point of view.

LN: Was there anything else you wanted us to know about the work, or that you wanted to share?

RB: Well, you know, you have an idea and then you proceed. Soon, these [Wave Sound] objects will be installed in the three parks. It’s always fascinating to try to imagine what it’s going to look like, and if it’s going to function.

That’s the beauty—and the scary part—of this process. Is it a good idea? Will it be respectful of the land? That’s the scary part for me: Is it a good thing that I’m doing?

I think those questions go back to when you take something from the land, and you make something, which is what we do as human beings—we mine the land, for its resources. So this we took the rock, in some manner, and put it into the object, which will be cast from aluminum—also a resource from the land.

I think the whole process, or the idea, the concept, is very basic—and maybe it’s ancient. But when it becomes an object and it’s fitting very close to the rock from which it came, will that be a good thing? I hope so.

LN: Thanks for sharing that vulnerability. I feel like people are not always so open about their insecurities in their work.

RB: Well, that’s a big part of it.

Rebecca Belmore’s Wave Sound will be installed June 27 to September 21 in Banff National Park, June 24 to September 21 in Pukaskwa National Park, and June 30 to September 21 in Gros Morne National Park, all as part of LandMarks/Repères2017.

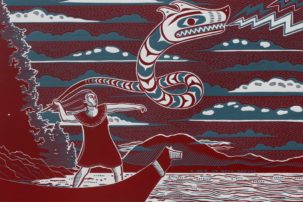

Artist Rebecca Belmore hopes her new work Wave Sound will encourage people to listen more closely to the land. Her process entailed site visits like this one on the shores of Lake Superior, at Pukaskwa National Park. Photo: Kathleen Ritter.

Artist Rebecca Belmore hopes her new work Wave Sound will encourage people to listen more closely to the land. Her process entailed site visits like this one on the shores of Lake Superior, at Pukaskwa National Park. Photo: Kathleen Ritter.