Lindsay Nixon: There is such a feminist matrilineal presence in your work. And obviously that comes through with your mother being in your work, and her being here with you at the Sobey Art Award ceremony. Can you reflect on that a bit?

Stephanie Comilang: Family has always been present in my work. It’s not really premeditated, but sort of happens afterward. I was looking for someone to voice the character of Paradise in my film Lumapit Sa Akin, Paraiso (Come to Me, Paradise). My mother lives in Toronto and at the time I was living in Berlin. We would Skype and she would help with translation, because a lot of my films include Tagalog. As she was reading the translation out, it kind of clicked that her voice was perfect. One, because the character of Paradise is female, feminine and more sympathetic and caring. But also because of the quality of the voice. My mom was talking to me through Skype and I would record her on my iPhone. So, there was this removed digital quality to the voice, which works well in my work because a lot of it has to do with technology and distance, and how we deal with them.

I identify as female. I’m a child of immigrant parents from the Philippines. Ideas around identity always come into play.

LN: What role do drones play in your films?

SC: I think about the drone in terms of how the camera can become a character. For me, the drone worked perfectly because it’s something that I could control myself, something that I could give human qualities to. In the same way, the drone can operate as a ghost or a spirit moving through space: the quality that you see with a drone is this ghostly way of looking at the world.

But then I realized that drones were initially used for war and surveillance. I wanted to subvert that and create something that was more feminine, something that was used for watching out rather than surveilling. To me, that equaled someone who was more femme.

LN: Your use of feminine drones brings up so much about intention and ambient technology. When I first saw your work, it was just these fun videos of femmes looking cool and dancing on subways. How does that all connect into your practice?

SC: I think you’re talking about a video that I made for a Taiwanese girl group in Berlin, “Killin’ the Breeze.” I was like, I’m going to do like a one-shot take: let’s shoot on the subway! The girls in the video were all dancers—pole dancers—and they were amazing. I was like, This goes together perfectly.

I identify as female. I’m a child of immigrant parents from the Philippines. Ideas around identity always come into play. I’ve talked about home as being kind of the base of my work, and something that is always circling around what I do. Yeah, and being, like, a brown femme, you know?

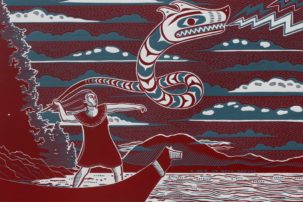

Stephanie Comilang, Yesterday, In The Years 1886 and 2017, 2017. 2-channel video installation, 9:49 min. Installation view at the Sobey Art Award Exhibition, Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton, 2019. © Stephanie Comilang Photo: Leroy Schulz

Stephanie Comilang, Yesterday, In The Years 1886 and 2017, 2017. 2-channel video installation, 9:49 min. Installation view at the Sobey Art Award Exhibition, Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton, 2019. © Stephanie Comilang Photo: Leroy Schulz

Stephanie Comilang, Lumapit Sa Akin, Paraiso (Come To Me, Paradise) (still), 2016. Video, 26 min. Installation view at the Art Gallery of Alberta. Photo Leroy Schultz

Stephanie Comilang, Lumapit Sa Akin, Paraiso (Come To Me, Paradise) (still), 2016. Video, 26 min. Installation view at the Art Gallery of Alberta. Photo Leroy Schultz

LN: You’re dealing with these themes of technology, networking and capitalism. But there’s such an incredible intimacy—it’s almost jarring.

SC: Again—it wasn’t something that was intentional. But the way that I wanted to create the characters and the way that I wanted to shoot was more intimate. I knew that I didn’t want the drone to be super high up. The drone used to film Lumapit Sa Akin, Paraiso (Come to Me, Paradise) flies closer to the ground to have more contact with the women who are in my film.

I also use a lot of cell phone footage [in the same] way that we use vlogs. The films have a diaristic sense to them. The way we are accustomed to having phones in front of us filming is a very personal way of recording ourselves.That factors a lot into the films that I make. Also, the writing is very personal. Paradise talks a lot about how she feels day to day, what’s going on, and how to find the other women. “I’m going through an existential rut,” her character says, and these are the things that she talks about.

LN: You brought up representation during your acceptance speech for the Sobey Art Award. Did you want to reiterate that here?

SC: Representation, for me, is everything. And growing up as a brown kid in Canada, I didn’t really see anyone who looked like me as a successful filmmaker or a successful artist. Having and receiving this award creates space for the younger version of me to see themselves, and that’s super important for me.

Stephanie Comilang, 2019 Sobey Art Award winner. Installation view of Lumapit Sa Akin, Paraiso (Come to Me, Paradise), Sobey Art Award Exhibition, Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton. 2019. Photo Leroy Schulz.

Stephanie Comilang, 2019 Sobey Art Award winner. Installation view of Lumapit Sa Akin, Paraiso (Come to Me, Paradise), Sobey Art Award Exhibition, Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton. 2019. Photo Leroy Schulz.