Spring always brings a fresh blossoming of art books to our shelves. Here are some top picks for the season.

Marcel Dzama: Sower of Discord, by Bradley Bailey, Dave Eggers, et al. Harry N. Abrams, 288 pp, $75.

Those who doubt either the variety or steady progression of Winnipeg-born, Brooklyn-based Marcel Dzama’s body of work need look no further than this survey catalogue, which tracks the artist’s career from its beginnings to the present. As Raymond Pettibon notes in his foreword, the title of the book is taken from Dante’s Inferno, referring to the damned who inhabit the eighth circle of hell due to the chaos they inflict in life, and who, in the afterlife, are punished by an endless cycle of demonic rending and reconstitution. Here, the “sower” might be one of the many characters frequently inflicting violence in Dzama’s drawings, sculptures and films, but it might also describe the artist himself, whose referencing of art-historical figures like Goya, Blake, Ensor and (notably and prolifically) Duchamp consists of a perpetual breaking down and building up. In addition to beautiful, accurate reproductions—the artist’s relationship with red is an epic romance—there are short stories by Dave Eggers, an intriguing two-part piece by Bradley Bailey (a biography and a taxonomy) and an interview with director Spike Jonze in which Dzama recalls, “One of my proudest moments in elementary school was when a teacher took away a drawing I made. I was drawing in class, got caught, and I had my drawing taken away. But the next day my teacher had laminated it and hung it on the side of his desk.”

On Architecture: Melvin Charney, a Critical Anthology, edited by Louis Martin. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 496 pp, $49.95.

The late Melvin Charney was a poet of facades. His major public artworks, from his intervention along Sherbrooke Street for the Montreal Olympics to his escarpment garden for the Centre for Canadian Architecture overlooking lower Montreal and the St. Lawrence River, all featured dislocated facades that served as prompts for urban memory. This homage to Charney assembles critical appreciations of his work, documentation of his projects and examples of Charney’s own theoretical writings on architecture. Together, they present a testament to one of Canada’s deep thinkers on the uses and abuses of architecture who turned his knowledge into one of this country’s first postmodern art practices.

The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium, by Eleanor Heartney, Helaine Posner, Nancy Princenthal, Sue Scott. Prestel, 256 pp, $43.95

Profiling 24 torch-carrying, prominent international artists (all women who came of age in the wake of second-wave feminism), this follow-up to the authors’ prizewinning After the Revolution is divided into four thematic sections, each of which contains six short, accessible, sumptuously illustrated essays alongside graphs that reveal the art industry’s persisting gender inequalities. As a rather male-dominated art season draws to a close, consider this a refresher course on the women leading the charge into battles still being waged today.

David Altmejd, by Trinie Dalton, Christopher Glazek, Robert Hobbs, Kevin McGarry. Damiani, 384 pp, $65.

Publishing a successful monograph on a sculptor—for whom three-dimensionality is key—is no easy task, especially one whose works are as faceted as David Altmejd’s. This new, long-awaited book from Damiani, however, is exacting in scope and luscious in form. Sensitive photographic views of Altmejd’s works are placed next to percipient texts by Trinie Dalton, Kevin McGarry and other contributors. A comprehensive appendix brings the book to almost 400 pages, making it nearly as indomitable and hulking as an original Altmejd creation.

Words for Art: Criticism, History, Theory, Practice, by Barry Schwabsky. Sternberg Press, 243 pp, $28.

The role of the critic in today’s art world has been a much-debated issue of late, but this volume of book reviews, written over the past two decades by Schwabsky (art critic for The Nation), should put naysayers to rest. Subjects range from Walter Benjamin, Clement Greenberg and the October circle to Peter Schjeldahl, Boris Groys and Sarah Thornton. Schwabsky takes each as an opportunity to parse the static fog of critical judgement, offering instead a series of thoughtfully grounded prompts that pivot and shift on the ever-evolving interplay of idea and perspective.

Your Everyday Art World, by Lane Relyea. MIT Press, 264 pp, $27.

Exploring the oft-championed operations of DIY culture, collaboration and networked identities, this book represents a much-needed critical examination of the mechanisms of the art world in a digital age. Relyea, who once positioned himself as an advocate for de-centralized, anti-authoritarian slacker culture, offers this book as a “belated mea culpa.” Throughout the text, he explores major trends that contribute to a modular (albeit dangerously precarious) existence for the creative class, and presents a powerful counterpoint to the glorification of “prosumer” culture.

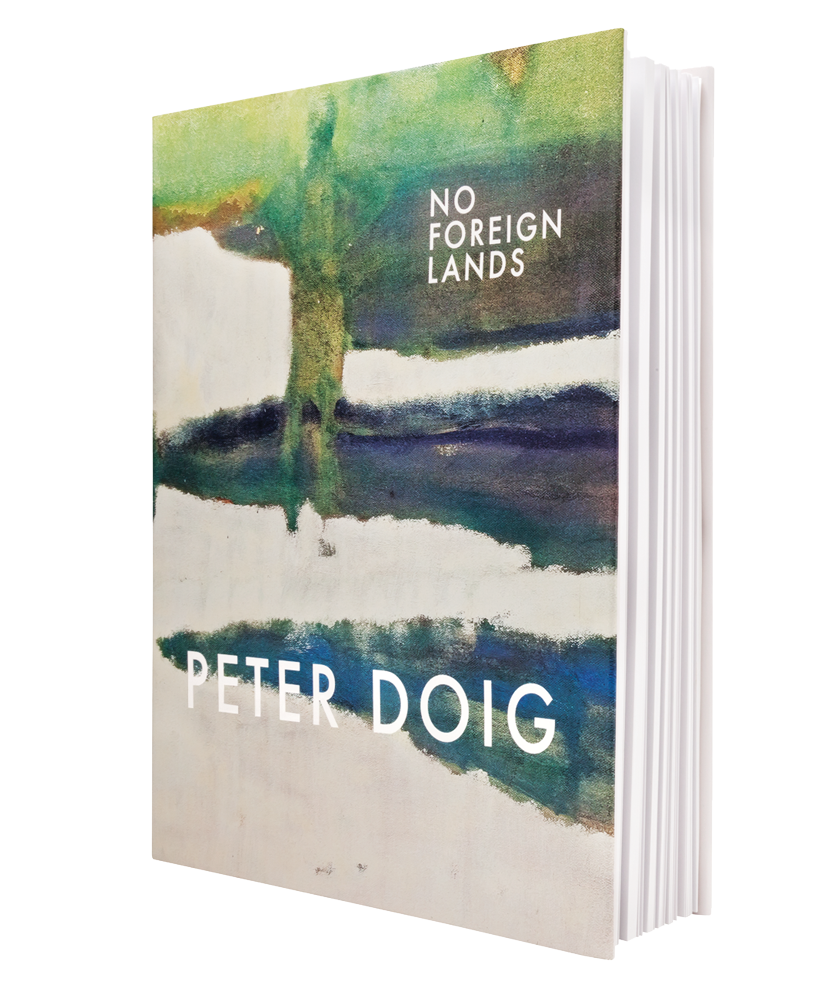

No Foreign Lands: Peter Doig. Hatje Cantz, 224 pp, $65.

Only Peter Doig can make paint look like curdled milk, and that slightly sour viscosity has proved a potent metaphor over the course of his career as a painter who has restored “dreamscape” to the working vocabulary of contemporary art. The spectacular reproductions in this survey catalogue make their own case for his importance, and the essays from Stéphane Aquin, Hilton Als and Keith Hartley are illuminating for their recapitulation of the links between his life and art. As Doig says in this book, “You have to own an image in your head, as well as own it on the canvas, as it were, before it becomes in any way believable…I never really understood what was so conceptual about Conceptual Art anyway—all painting, pretty much, is conceptual.”

The original form of this article appears in the Spring 2014 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, visit its table of contents. To read the entire issue, get a copy on newsstands or the App Store until June 14.