“…psychopathy has become endemic among artists and writers, in whose company the moral idiot is tolerated as perhaps nowhere else in society.” –Clement Greenberg, 1949

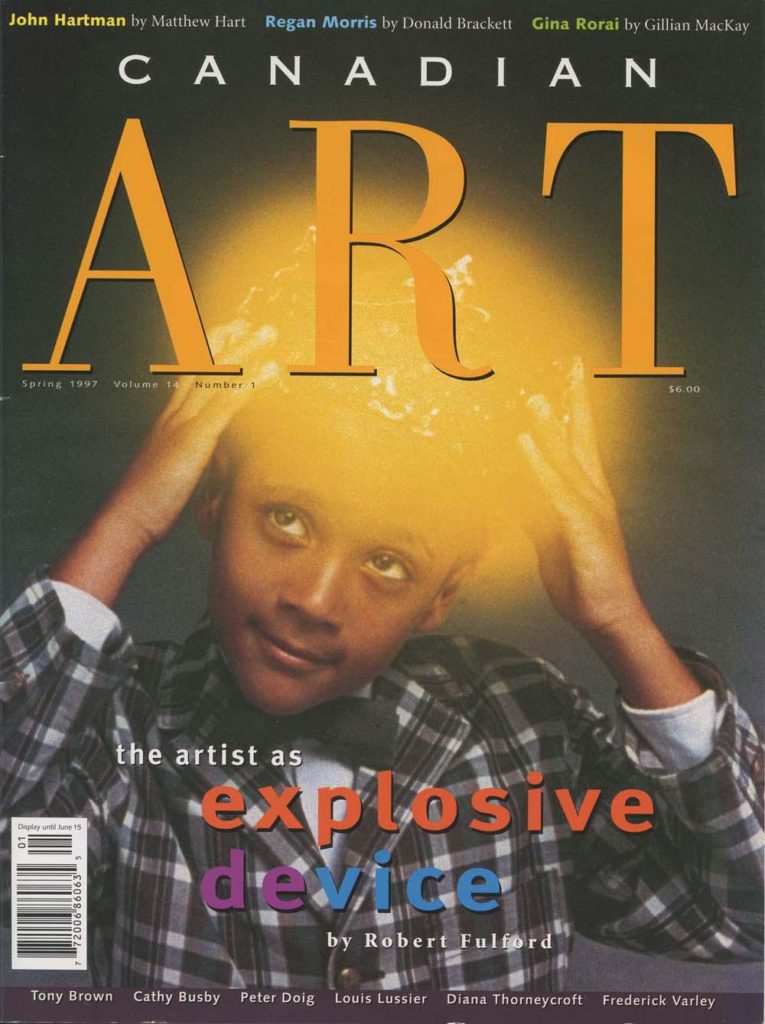

A famous painter lives in public fantasy as a bomb that may go off at any moment, scattering the shrapnel of genius in all directions while endangering everyone in the vicinity, not least himself. Certainly that’s how Pablo Picasso appears in Surviving Picasso, how Jean-Michel Basquiat emerges in Basquiat, and how Andy Warhol looks to the woman who tries to kill him in I Shot Andy Warhol. Artists live risky lives, and the risk is not theirs alone. They seem to stand outside the usual rules of conduct—they have, to adapt Greenberg’s remark, a licence to practice moral idiocy. The result, in each of these movies, is melodrama, the transformation of complex life into morality tales simple enough for afternoon TV.

Makers of feature films, true to the tastes of our historic moment, meet art only on the level of biography. We are a story-telling civilization (it’s our principal activity), and we expect life to present itself as orderly narration. We want an artist’s career to be a structured parable—and artists often co-operate, some unknowingly (van Gogh), others out of narcissism (Warhol), still others because they appear to be living out a script someone else wrote for them, lurching toward the disaster of an early grave (Basquiat).

So begins our Spring 1997 cover story. To keep reading, view a PDF of the entire article.