From 1963 to 1971 to 2017, and from Birmingham to Attica to Toronto, a new season of shows organized by the Ryerson Image Centre has set out to highlight images of police repression and black protest.

Just opened and running until April 9 are the shows “Attica USA 1971: Images and Sounds of a Rebellion,” “Birmingham, Alabama, 1963: Dawoud Bey/Black Star,” “Adam Pendleton: My Education, A Portrait of David Hillard” and “From the Collection: Sister(s) in the Struggle.” Then, opening February 2 and running until February 26 at the Gladstone Hotel is the related exhibition “No Justice, No Peace: From Ferguson to Toronto.”

The RIC is presenting all the exhibitions in partnership with Black Artist’s Network Dialogue, a Toronto organization dedicated to supporting, documenting and showcasing the artistic and cultural contributions of black artists and cultural workers in Canada and abroad.

“I think what these shows do is amplify the conversation,” says photographer Jalani Morgan, whose images of Black Lives Matter in Toronto are included in the “No Justice, No Peace” show. “It is already happening in the community, but exhibitions like this at Ryerson really allow for the conversations to amplify. And I’m very happy with the fact that that’s happening.”

Originally, says RIC director Paul Roth, he and his team thought of the shows as being themed on black protest, period.

“But looking at the images, we saw it was more about the use of police by the state to stamp down dissent and limit and define…how people exist in society,” Roth says.

The state’s stamping down of dissent clearly comes across in many of the photos on view.

In “Attica USA 1971,” some of the photos that served as evidence in Attica prisoners’ legal cases are numbered and labelled systematically. The evidence display ends with photographs showing bodies themselves labelled with the scrawled codes P-1, P-27 and P-28—bodies of dead prisoners, marked with the state’s inventory details.

In other photos from this legal archive, recaptured Attica prisoners assemble outdoors in regimented, snaking lines, all naked, hands folded on their heads, bodies vulnerable to the armed (and clothed) guards nearby.

And in “Birmingham, Alabama, 1963,” photos show black protesters being subjugated to powerful streams of water, their bodies literally pressed up against walls, trees and ground by the state’s authority.

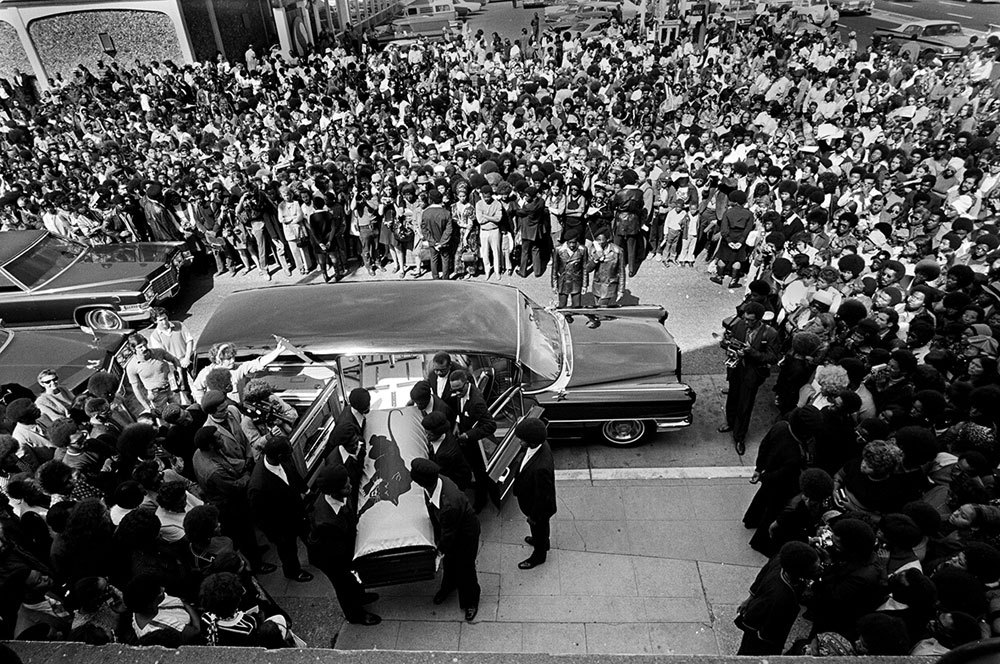

Stephen Shames, Black Panthers carry George Jackson’s coffin into St. Augustine’s Church for his funeral service as a huge crowd watches, Oakland, California, USA, August 28, 1971. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the Steven Kasher Gallery, New York.

Stephen Shames, Black Panthers carry George Jackson’s coffin into St. Augustine’s Church for his funeral service as a huge crowd watches, Oakland, California, USA, August 28, 1971. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the Steven Kasher Gallery, New York.

Protest in Attica and Birmingham remains “a key story for us to think about today given [current] protests against systemic oppression,” Roth says.

Hence the title the RIC has applied to this entire season of shows: “Power to the People: Photography and Video of Repression and Black Protest.”

Julie Crooks, a BAND curator and a University of Toronto sessional lecturer, focused on archival images of activists Angela Davis and Kathleen Cleaver when creating the show “Sister(s) in the Struggle.”

“I think now because of our changing political tide, especially in the US—but we cannot be smug in Canada, because those same sentiments are here—I think to grab on to the kind of history that is embedded in the work that these women did” is vital, Crooks says, as is approaching their activism with a “renewed eye.”

Crooks hopes that the images of Davis and Cleaver provoke thoughts in viewers about lesser-known women activists, too.

“I think what I was trying to do as well was to pay homage to the unnamed black women who were part of that struggle, and continue to be part of that struggle,” Crooks says. “I mean, there are thousands of women in the trenches doing what they have to do. So the show is about the named and the famous and the celebratory, but it’s also about those many unknown and unnamed.”

Today @blklivesmatter TO checked John Tory today to demand an end to carding. #blacklivesmatter

A photo posted by Jalani Morgan (@jalanimorgan) on Feb 23, 2016 at 4:12pm PST

In terms of documenting some of today’s black activists in Toronto, Morgan—who used to shoot fashion photography with an agency before heading back to school to study anthropology and African studies—says he was motivated in part by a schism he saw in other photos of black protest.

“Oftentimes I would see images of protests of racialized black people, and it wasn’t created by us, you know what I mean? It has this separation. Great photography, lovely composition, lovely light”—but there was something that didn’t feel quite right to Morgan.

“So I was like, I’ve been taking pictures for a long time.” Morgan says. “I think I can relate to this—on the photography level, but also on the oppression level.”

In a way, Morgan says, he wishes that he didn’t have to make photographs like the ones in the Gladstone show—many of which first appeared on his social-media feeds when he couldn’t find conventional media outlets that would take them.

But as black protest remains necessary, and repression of it ensues, Morgan says, so must photography of such protest.

“As long as there’s oppressive behaviours by the police, by the institutions, there’s going to be, unfortunately, something that has to reflect that,” Morgan explains. “I don’t want to make these photos. But if not me, then who?”

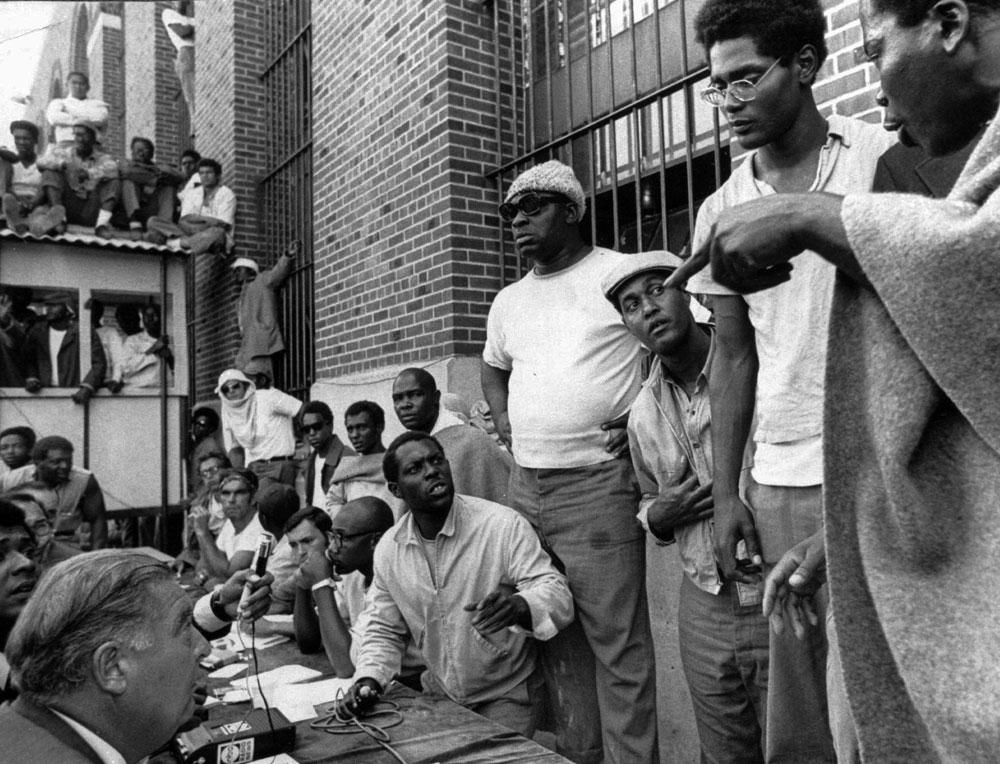

Stephen Shames, Inmates of Attica State Prison negotiate with state prisons Commissioner Russell Oswald at the facility in Attica, NY, USA, September 10, 1971. Courtesy the Associated Press.

Stephen Shames, Inmates of Attica State Prison negotiate with state prisons Commissioner Russell Oswald at the facility in Attica, NY, USA, September 10, 1971. Courtesy the Associated Press.

This article was corrected on January 20, 2017. The original referred to Julie Crooks as a University of Toronto professor, rather than as a sessional lecturer.

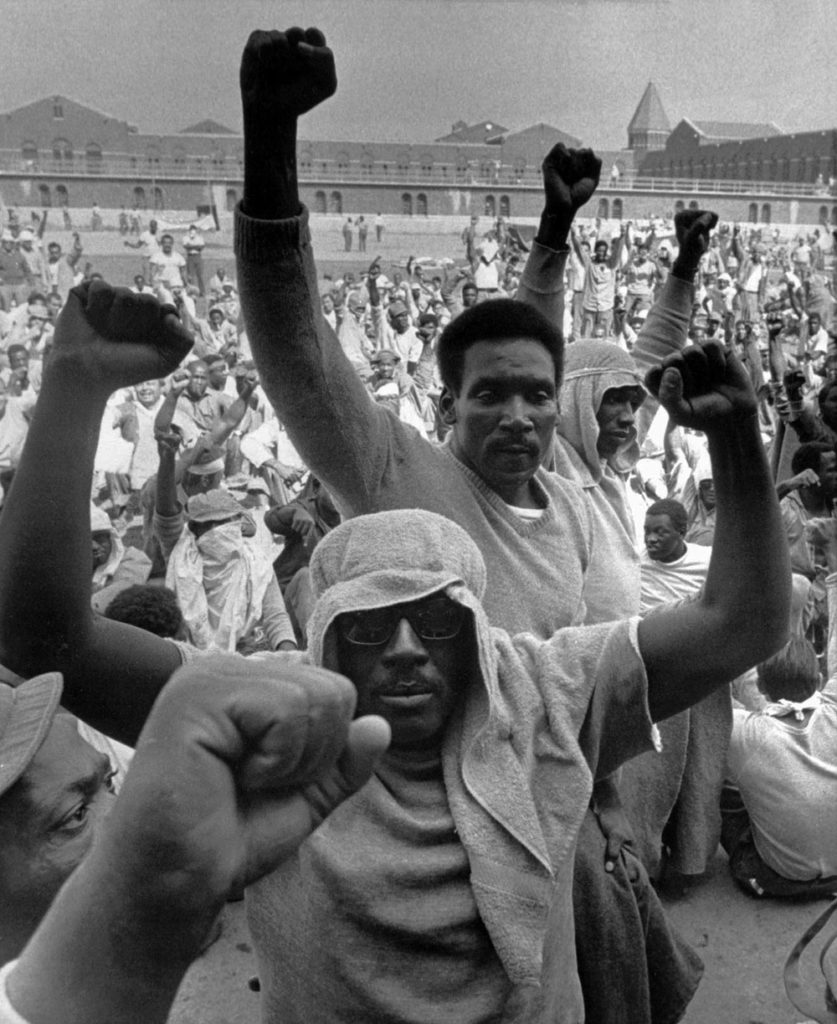

Bob Schutz, Clenched fists at Attica State Prison, Attica, NY, USA, September 10, 1971. Courtesy of the Associated Press.

Bob Schutz, Clenched fists at Attica State Prison, Attica, NY, USA, September 10, 1971. Courtesy of the Associated Press.