Last weekend, Toronto-raised photographer Petra Collins was dressed in glittery silver ankle boots and a grey hoodie, hugging friends at the opening of her first solo exhibition in Canada at Contact Gallery, a small space in a renovated warehouse on Spadina Avenue. Collins hasn’t returned to the city with much frequency since leaving for New York four years ago at the age of 20 with either one or two suitcases—the story varies in different interviews. In New York, she established herself as an in-demand hyphenated creative: artist-fashion photographer-muse-curator-model. She has published two art books, shot campaigns for Nordstrom, Adidas and Gucci, created a short film for Tate Modern, filmed a music video for pop star (and fellow Canadian) Carly Rae Jepsen, shown installations at the MoMA and amassed an Instagram following of more than half a million people. She posted a photograph from the exhibition on Instagram on April 27 announcing her talk at Contact Gallery, and 12, 474 people liked the post.

In the gallery, Collins leaned, arms crossed, against a large vinyl print of a photograph of her suburban childhood home to have her picture taken, while a well-dressed crowd, primarily consisting of young women, began to filter into the room, watching Collins at work. “I really prefer to be behind the camera,” Collins told the photographer.

The large images hung throughout the gallery were quintessential Collins, who has become synonymous with a particular depiction of teenage girlhood. There were hazy suburban scenes in cotton-candy pastels and sun-dappled portraits of young women and older family members in soft focus. “The show has so much to do with my childhood and so much to do with the thought of loss,” she told me. “The work comes from two different series that are both very personal to me—they’re of my family. I had never photographed them in this way before…the way that I feel about them is really how the images came out.”

The pictures look like something out of a fashion magazine—romantic, a little saccharine—which is unsurprising, given that many of them originated in an editorial project. One series was shot in Toronto, and the unreleased images from that body of work will be collected into a book published by Rizzoli this fall. Other photographs were created for the fashion publication A Magazine Curated By. Gucci designer Alessandro Michele made selections for the issue, asking artists including Collins, Catherine Opie and Nan Goldin for contributions. “We were just given one sentence, which was ‘blind for love,’ and then let do whatever we wanted,” said Collins. “My family is kind of divided, half of them are in Budapest, and half of them are here in Canada, so I decided to go back and shoot them in Budapest last summer after not having been there in eight years.”

The show marks a first for Collins, and also for the gallery. Beyond being her inaugural solo exhibition in Canada, the show includes a large photographic billboard, towering over Spadina Avenue, which offers Collins a foray into public art (though her commercial campaigns have graced plenty of public spaces). Linked to the Scotiabank Contact Photography Festival, the largest of its type in the world, Contact Gallery’s exhibition is one of the festival’s tent-pole events. Past exhibitors at the gallery have often been mid-career artists with plenty of international venues on their CVs: American Christian Patterson, Italian Lorenzo Vitturi, the duo Rob Hornstra and Arnold van Bruggen among them.

“This year, we decided to celebrate Canada. So we started with a big laundry list, and at the start it was big, senior names, like Michael Snow or Jeff Wall,” said Contact’s executive director, Darcy Killeen. “After some further thought and investigation we thought, let’s try and find a young artist…. I think the next day we just called Petra and she said yes right away.”

The timing coincides with Collins’s recent announcement that she wants to move away from the images of girlhood that made her famous. “I’ve been taking photos since I was 15 and all my photos have dealt with being a teenager, and as much as that is fascinating, I don’t think it’s my story to tell anymore—it’s a chapter I want to close,” she said. Next up: she likes the idea of feature films and more public-art commissions. “Putting work out to the masses, I think, is the most important for me,” said Collins. When you have a fanbase the size of hers, the masses are just a question of scale.

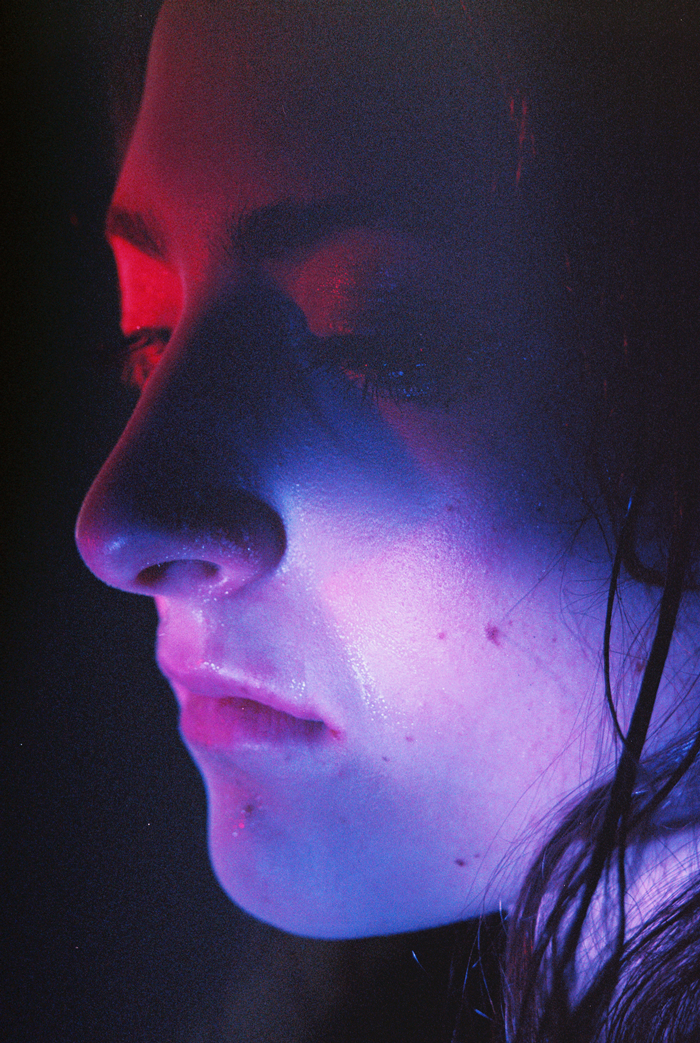

Well before Collins began her talk at 2 p.m., the gallery was filled with bodies and the crowd spilled into the hall. Over the course of the day, the gallery estimates that some 1,000 people dropped by to see Collins and her work. A woman in rose-gold Birkenstocks craned to see the purple and neon-lit portrait of Collins’s sister, Anna, depicted with tears streaming down her face. “This is stunning,” the woman said to her friend.

“She’s so cool,” sighed another attendee after catching sight of Collins.

The artist started discussing the sources of the work, how she loved the ghostly quality of the images, the importance of keeping a sense of intimacy on set. There was a scramble to ask questions and get photos with Collins, and the crowd started mingling, looking at the work and venturing into the gallery’s other room for drinks.

“I think this might be the first time at an opening where we have to check for IDs at the bar,” said an employee.

Caoimhe Morgan-Feir is the associate editor of Canadian Art. She is on Twitter @CMorganFeir.

Petra Collins, Anna (Tear), 2015.

Petra Collins, Anna (Tear), 2015.

Petra Collins, Anna and Kathleen (Rainbow), 2016.

Petra Collins, Anna and Kathleen (Rainbow), 2016.