On the fifth floor of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the museum’s canonical installation-narrative of the history of Modernism begins with a painting by Paul Gauguin. The Moon and the Earth (1893) depicts the naked female moon goddess Hina imploring the male Earth god Fatou to give humans the gift of everlasting life. There, as the curtain rises on the 20th century, is an image of Polynesian myth, as understood through the eyes of an itinerant Parisian.

A few paces deeper into that gallery, the curators have installed Henri Rousseau’s famous jungle odalisque The Dream (1910), a purely imaginative confection complete with exotic foliage, a snake charmer and crouching lions. (Rousseau, in fact, never left France.) Finally, turning left, you meet the knockout punch of Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the notorious brothel scene from 1907. Picasso’s women seem to erupt from within, their faces morphing into African masks like those the artist had encountered in the halls of the Palais du Trocadéro.

Surging with the wealth generated by its colonial expansion around the globe, Europe was also experiencing cultural blowback. Worlds were colliding, Indigenous cultures were being violently effaced and, as a correlative to that barbarism, European artists were hungrily clutching at the material evidence of these (to them) exotic cultures, and the new ways of seeing and understanding they suggested. African masks, Japanese prints and, later, the tribal objects of the Inuit and the people of the Pacific Northwest Coast, which would be avidly sought by the French Surrealists: what would Modernism have looked like without colonialism and the cultural aftershocks to Eurocentrism it ultimately set in motion?

Peter Doig, now 54, was born in Edinburgh, the son of a Sri Lanka–born Scots accountant employed by an international shipping company. Thus, he entered life an inheritor of that colonial legacy. Yet the intervening half-century has afforded him the chance to witness the shift from colonialism to global capitalism, and the resulting accelerations of cultural convergence that have come with it.

From Doig’s earliest years, the family floated around the Commonwealth, borne by the tides of opportunity. Raised through his boyhood in Trinidad, Doig moved to Canada when he was seven, his family bringing with it memories of the tropics and a smattering of Trinidadian paintings his parents had collected, as well as his father’s own amateur paintings of tropical subjects, which hung on the walls of their home. They first settled in Baie d’Urfe, on Montreal’s West Island, then in the Eastern Townships, where Doig grew up skiing and playing ice hockey and pursuing other quintessential Canadian pastimes. When he was entering Grade 10, the family moved again, this time to Toronto, where he roamed the urban ravines with friends, immersed himself in the city’s punk and experimental-film scenes, and visited the vanguard artist-run centre A Space Gallery.

Finally, at 19, following a period out West working on the gas rigs in eastern Alberta and a year at an alternative high school in Toronto, he left for art school in London, England, where he started to turn those Canadian memories and influences into the paintings that would make his international reputation. For 12 years now, though, he has been resident back in Trinidad, with regular teaching stints in Düsseldorf. Asked where he feels most at home, he says London, but he does so tentatively, as if the whole idea of belonging somewhere is a kind of unattainable, elusive ideal.

When I arrive at his temporary Tribeca studio, a few hours after my visit to MoMA, it is clear that the complexity of his own trans-Atlantic cultural past remains a muse to his art. The studio table is littered with books and catalogues (Ferdinand Hodler, Henri Matisse, Le Corbusier), but he draws my attention first to a catalogue for a show he has just seen at the Morgan Library & Museum: a small and beautifully focused exhibition about Edgar Degas’s Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando (1879). Given what I have come here to discuss—the notion of painting as a document of our moment’s uneasy cultural compressions—I notice that the female aerialist in the painting is black. “Look at this,” he says, showing me the book, noting the dynamic placement of the figure against the vaulted ceiling above. “You don’t tend to hear much about Degas, but this is interesting.” Here at the circus, Miss La La, the mixed-race Prussian-born star of the travelling Troupe Kaira, hangs by her teeth above the crowd—an image suggesting extremity and sublimated violence. It’s a subject to keep post-colonial cultural theorists up for days. For Doig, it’s a bone to chew. Who knows where it will turn up in his art? If it will turn up? But today, here, it has his attention.

Propped around us in the studio are the beginnings of a new group of paintings, some of which are destined for Edinburgh. The Scottish National Gallery is preparing a survey of his last decade of work: “No Foreign Lands: Peter Doig.” (The title is drawn from Robert Louis Stevenson: “There are no foreign lands. It is the traveller only who is foreign.”) In winter 2014, the show tours on to the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, to a city where Doig spent a few years as a young man between degrees (odd-jobbing as a colour mixer and painter for a theatrical scenic artist) before completing his art education in London. A major retrospective exhibition at the prestigious Fondation Beyeler near Basel, Switzerland, looms on the calendar right behind it. As Doig prepares for these hurdles in New York, he has settled into a somewhat monastic regime of morning ice hockey at Chelsea Piers (his strip is hanging to dry in the studio basement), painting and reading. A mattress on the floor in a corner is framed with pink-striped sheets, strung up like a makeshift fort. Ever the nomad, Doig is living the life of a continental drifter.

His new paintings’ themes are consistent with his work of the past decade or so, since his decision to return to Trinidad with his then-growing family. In an earlier meeting at the New York space of Michael Werner Gallery, we had laughed about the roster of those who could claim Doig as their own, particularly since 2007, when his painting White Canoe (1991) set the world record at $11.3 million for a living European artist at auction: Canada for his years growing up (his parents still live near Grafton, Ontario); England for his art-school sojourns at Wimbledon School of Art, Saint Martins School of Art and Chelsea School of Art; and Scotland for the fact that he was born there, and for his Scots parentage. I suggest that the Trinidadians may soon join the queue to lay claim, though Doig says: “Trinidad is for Trinidadians. I would never want to try to represent Trinidad. Trinidadians should do that.”

Still, in Trinidad, he is no tourist. His engagement with the cultural community there has been a vital part of his artistic development, and he speaks with respect of the island’s tortured history of colonization by the Spaniards and British. (The island would only gain independence from British rule in 1962, when Doig was three years old.) The Studio Film Club, which he started with Trinidadian painter Che Lovelace, was for eight years an important gathering place for the island’s artistic community. As well, he adds, this past decade in Trinidad has been “the only time I have ever painted what’s in front of me,” working more than is his custom directly from lived experience. Characteristically, his practice has been to paint Canada from the vantage point of London, or, as he was doing again in the crunch this spring, the Caribbean from the perspective of a Tribeca studio, in addition to lifting images from archives, films, postcards, tourist brochures and the tide of mass media. Displacement has been part of his mechanism of inspiration. “At a distance,” he says, “the image is allowed to develop on its own, outside of its original context.”

The paintings stand around us half-finished. In one, two empty hammocks are suspended on a veranda, the white shutters behind evoking Matisse’s renderings of the south of France and North Africa, reductive descriptions of the spaces of European indolence. Perhaps, Doig says, they will come to be inhabited.

On another wall, a large vertical canvas depicts a standing spearfisherman with goggles on, his face obscured in a way that one can read as menacing—like many of the masked figures who appear in Doig’s work. The spearfisherman is accompanied by a seated figure in a yellow raincoat. The painting recalls a pair of fishermen Doig and his friend chanced upon on one of their habitual kayaking trips on Trinidad’s wild North Coast. As is Doig’s custom, these subjects are hard to interpret precisely. Is this raincoated figure friend or foe? What is happening here? The racial identity of the subject is ambiguous.

As with the subjects of some of his earlier series—like his roller-skating girl (whom he glimpsed in Central Park), or his beach walker holding a dead pelican (another chance encounter in Trinidad), or his boatload of young men at sea (taken from an Indian postcard and transposed to a Trinidadian locale)—Doig will flip the racial identities of these figures back and forth from black to white as he moves between painterly iterations, leaving the matter of race precisely ambivalent.

Another large half-finished painting, propped against the wall, depicts a man on horseback pictured against a tropical backdrop of shore and sea. “I was remembering here Goya’s painting of the Duke of Wellington,” says Doig, referring to the famous 1812 equestrian portrait now in Apsley House, London, whose pose he has borrowed here, “but I was also thinking about the arrival of the Spaniards in Trinidad—of how they came by sea,” starting with Christopher Columbus’s third voyage in 1498. The painting suggests an uneasy fusion of realities, and that disjuncture is where its energy lies. “The painting also comes out of something quite personal,” he adds. “A memory I have of riding on the back of a swimming horse, something I experienced in my childhood in Quebec.” Seeing is refracted through multiple cultural lenses; Doig belongs wholly to none of them.

His works from the early 1990s leaned heavily on the Symbolist precedents of Edvard Munch and Emil Nolde, but Doig’s frame of reference is always expanding, as he searches for images that will snag consciousness, becoming puzzles to be worried at in paint. Once he finds that image he is apt, like Munch, to return to it over a period of years, as he has the figure of the drifting canoeist from the 1990s (equal parts Tom Thomson, Duane Allman and Friday the 13th), or the archivally sourced image of a hooded Franklin Carmichael sketching in a northern Ontario landscape, which Doig reiterated in a dazzling series of works in that same decade. “There was a Munch show in Paris that I saw a few years ago,” he tells me. “You went into the first room and there were his greatest hits. And then you walked into the next gallery and there he was painting the same pictures 30 years later. The hair was just standing out on the back of my neck. Munch had so much commitment to the images that were vital to him.”

Some of Doig’s artistic points of reference are, of course, Canadian. In our earlier meeting, we had spoken about David Milne, and the historic artist’s atomization of the field of vision. (“There’s no hierarchy to what’s important,” Doig said, admiringly.) He has looked carefully at the Group of Seven, and in his student days used to sometimes visit the library at Canada House on Trafalgar Square to leaf through tourist brochures depicting the Canadian landscape, searching out the roots of his own belonging. But we had also talked about contemporary Vancouver photoconceptualist Jeff Wall, whom Doig respects for his ability to craft pregnant and timely images loaded with complex signification, and for his learned engagement with the history of art. Wall, too, explores the edgy interactions of race in a diasporic world, with people coming together in urban space in ways that seem combustible.

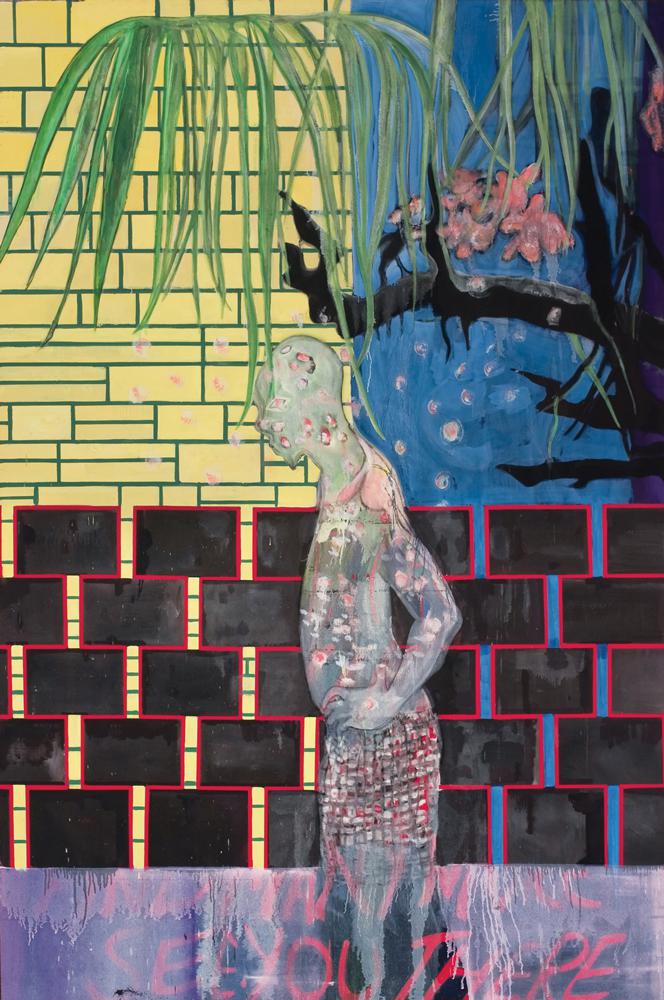

Also in his thoughts these days is Canadian Impressionist James Wilson Morrice, whom Doig describes as “the Scots Montrealer,” and who is clearly felt as a kindred spirit. “He made absolutely beautiful paintings of Trinidad,” Doig says. “I have often thought of doing a really big version of a Morrice sketch, because the openness is just incredible—the amount of atmosphere he is able to catch in a very limited amount of information.” Like Morrice, who often painted light and shadow playing across walls of mosques or souks (in, for example, Outside the Mosque, from 1913), Doig has made a study of walls—those impediments that obscure our view, and presumably, on a metaphorical level, our understanding, of what lies behind them.

Doig tells me, “In downtown Port of Spain, there is a big prison—it was obviously built in colonial times—and it occupies a whole city block. It’s just a big yellow wall; it looks like it has been painted with Colman’s mustard powder. It’s very dry. I have often thought of painting it. I know people who have been in that prison and it’s very grim, but there is no tradition of investigative reporting there, so nobody really knows unless they have been on the inside. You just hear the stories.” He adds, “The thing is, it’s right in the middle of town, so the people inside can hear daily life going on all around them. The carnival passes right by it.”

His Painting for Wall Painters (Prosperity P.o.S.) (2010–12), which was shown last fall in Doig’s exhibition at Michael Werner Gallery in London, records another such wall, this one from a bar in Port of Spain. Its worn and pitted surface is decorated with the painted flags of a host of then–newly sovereign Caribbean and African nations, and one can just see the open ocean beyond it, framed by islands and palms. The rampant Lion of Judah, a symbol of the Rastafarian faith, dominates the left-hand side of the composition. In another, smaller painting from the same show, the crowned lion seems to disport itself on a beach, framed above and below by bands of green and red. Is this a painting of graffiti, or a kind of landscape? Does Doig’s painting let us into three-dimensional space or block us out?

Doig’s earlier Metropolitain (House of Pictures), from 2004, is similarly complex. The painting depicts a European man in a top hat (the figure is a quotation from Honoré Daumier’s famous mid-19th-century painting, The Print Collector) examining what is in effect a wall of paintings, including Doig’s beach scene Pelican, painted that same year. Yet the wall seems curiously diaphanous, and through it one can partially view a tropical landscape. The wall both obstructs and permits perception.

Doig pictures his collector/artist as a kind of clown, a dishevelled bohemian figure that he came back to several times in the paintings of this period. “For centuries in Trinidad there has been a carnival character based on Europeans,” Doig tells me, referring to the tradition of public masquerade and celebration that developed after the abolition of slavery in 1834. “He wears a top hat and has a red nose and a white face—because of the sunburned noses and powdered skin of the white visitors. Carnival was the only time of release. The Trinidadians could mock the Europeans, dressing up like lords and ladies.” The painting seems to express humility as Doig contemplates the limits of his own understanding. He allows that this is a self-portrait: the view at the top of the painting, he says, is the view from his studio in Port of Spain. He adds, “The painting is really asking the question: Why have I come here?”

“It is hard not to see it as exotic,” Doig says of his adopted island home, “because with European eyes, with North American eyes, you see things that are just so startling—everything down to the sheer fact of colour, or a dead pelican, or five dead dogs on the road on your way to the studio, or a dead man on the way to the studio, even. There are things there that you don’t see in European or North American society.” That shock and estrangement—and the difficult stretching of consciousness that arises from such abrupt revelations—registers in his art.

Which brings us back to Gauguin. Revisiting Gauguin, looking at the catalogue for Tate Modern’s 2010 retrospective, I have more questions about the French expatriate and the meaning of his art; I now detect a darker tinge to his record of Polynesia. Far from being a paradise, this is an Eden laced with threat, and inhabited by people who seem unknowable, obdurate. In many of the paintings there is a sense of malaise and a perspectival incoherence. In some, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s The Purao Tree (1897–98), space seems to break down into an inchoate composite of blues, and it becomes unclear if one is looking at the ribs of a decomposing carcass or the fronds of a leafy palm. “I think it’s much more questioning, really,” says Doig of Gauguin’s work, “as if he is amazed by it, overwhelmed by what he is seeing.” He wonders aloud if we are not now indebted to the artist for the freedom he took to explore the anxieties engendered by colonialism in that early modern moment. In this, I suggest, Gauguin is not unlike our own Emily Carr, whose discomfort with her colonial identity (and the assigned gender roles prevalent in Victorian culture) spurred her curiosity about Indigenous peoples—even as she indulged her period’s romanticizing notions about them. Awkwardly, searchingly, these artists broke trail.

“The thing with Gauguin is that the mood is very strange,” says Doig. “There is a feeling of being quite daunted by what he is seeing.” After a moment, he adds: “In the tropics, you see, there’s always this fact of the 12 hours of darkness. I think you can sense that in Gauguin, too. There is the area of light, where you are, but then there is the forest beyond.”

This is a feature article from the Fall 2013 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, visit its table of contents. Find additional works by Peter Doig at canadianart.ca/doig.