It was Patti-mania this past weekend in Toronto. Legendary musician, author and artist Patti Smith was in town to celebrate her “Camera Solo” exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario, with a packed schedule of talks, signings and, of course, concerts: two at the gallery’s intimate Walker Court space as part of their “1st Thursdays” program, and one at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre on Saturday.

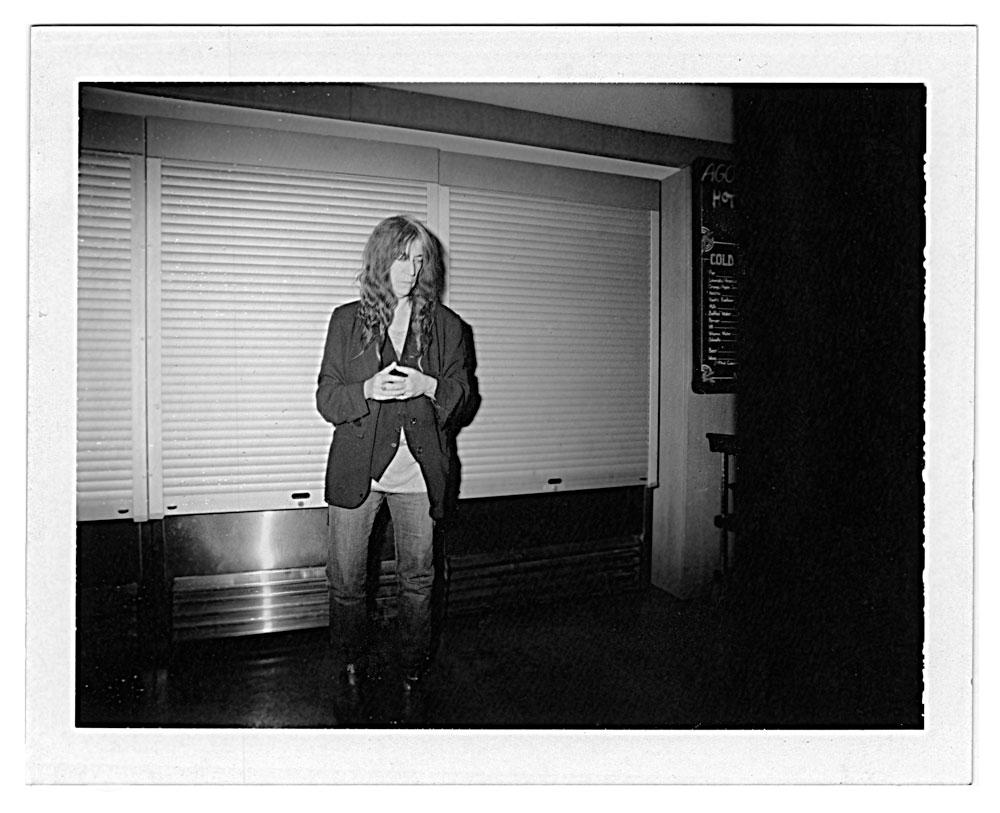

Canadian Art had the privilege to speak with Smith under unique circumstances. Photographer and filmmaker Steven Sebring was in town on Friday to help her introduce the AGO’s screening of Dream of Life, the 2008 documentary about Smith that was ten years in the making. Unsurprisingly, Smith and Sebring are longstanding friends, and she urged us to sit down with the two of them. What resulted was a casual chat about photography, the life of objects, the contemporary cult of celebrity and more. Afterward, writer, artist and Canadian Art editorial intern Sam Cotter was on hand to take black-and-white Polaroid photographs of Smith and Sebring. Please click on the “photos” icon above to view them.

David Balzer: You guys are both photographers. Do you discuss photography together?

Steven Sebring: I’ve always supported her.

Patti Smith: We look at each other’s pictures and tell each other what geniuses we are! [laughs]

SS: She gets all those cameras from me. I take total credit for that. I supply her with those things.

PS: I do go through Polaroid cameras, because they’re not meant to travel the world and to be dragged across the desert and to be near the ocean and be in extreme hot and cold, so he has to supply me with a bunch of old vintage cameras. But where’s the film to put in it?

SS: I’ll get you the film. It’s got to be Fuji now, though.

PS: We look at the photographs of others. Just like this Josef Sudek show [currently at the Art Gallery of Ontario]. We’re both completely overwhelmed by it. Such a beautiful show. We’ve talked about the printing process. Steven is a real photographer. I mean, I take photographs and…

SS: What does that mean?

PS: It means that in every way, you are involved in the technology, the paper, the light. You do it professionally. You study. You work with different kinds of paper and you’re experimental; you work with albumen. I take my pictures and I’m not technical at all. I know what I want, I take the picture I want, I have a silver print made of it. And the only difference between the photograph that I take and the print is that the silver print is on matte paper, which is my choice. I don’t Photoshop; I don’t do anything. Steven has a whole range of knowledge that’s completely overwhelming. So I wouldn’t compare us at all.

SS: Well the thing we can compare each other on is that we love our mistakes. And I actually strive for the mistakes. Even if it’s new technology, I just want to fuck it up. I want to use it as if it were a Polaroid camera. That’s my challenge. And that’s the way the film is, too. It’s very real. And if I’m shooting digital cameras now, like the biggest cameras you can get, it’s going to look like that.

PS: In other words, both of us can fuck anything up.

SS: We like to fuck it up.

DB: You did a show together as well at Robert Miller Gallery in New York in 2010.

SS: It was called “Objects of Life.”

PS: We’ve actually collaborated a lot.

DB: What was the connection between the documentary and the exhibition?

SS: For me, as an artist and photographer, I felt compelled to photograph her things that were in the movie. It’s sort of another experience for me. So I photographed her childhood dress, or Robert [Mapplethorpe]’s urn, or her cameras, or her boots. Emotionally, it was something else for me, because I’m a photographer as well. We had these really incredible photographs. And then we had great imagery from the film. So I just felt compelled to do a show with her and show all these things and call it “Objects of Life.”

PS: The interesting thing is that we both have a relic sense of the importance of objects. We each have our own vocabulary in terms of that, but different technique. What I really liked about doing a show together was, I take photographs of things and often the photograph has more of the atmosphere of an object, the feeling of the object. And Steven, because of the way he works technically, even with large Polaroid format or something, was able to do these beautiful, pristine pictures of these objects. So he made huge pictures of, like, the neck of my ’30s Gibson guitar, or the Persian necklace that Robert gave me, or my old ’70s road case. And I can’t take pictures like that. His are colour. They’re strong; they’re bold; they’re simple and big.

[The exhibition] was different types of portraits often of the same thing. Where in my work you feel the atmosphere or innocence of my little childhood dress, with Steven you see every fold, and the stitches. It was a nice melding. But also, he makes large-format pictures and sometimes I’ll write on them. I like to do a lot of handwriting. I had a plaster cast of William Blake’s head, and I think there was a photograph of it in the show. And he did a massive photograph of it, and then I covered the head with Blake’s poetry in a very calligraphic style. So, we had some installations. We like working together. I mean, he gets into areas that are so far out technologically that I don’t even want to look at them; it’s just frightening. We have our own lives and everything, but when they intersect, it’s a nice brotherhood.

DB: Your photographic work is so object-based, and there is a lot of photographic theory about photographers as desirous and desiring people: I can’t have that thing so I will photograph it. Patti, you obviously work within a very improvisational mode but I do wonder what goes through your mind when you finally decide that an object needs to be photographed.

PS: You said something very interesting: that idea, not of appropriating, but having something of it. It’s like why Indians… they would say that an Indian didn’t want his picture taken because he felt that something of himself was taken away by the photographer, or drained from him, and put on the photographic paper. In a way, I mean I never thought about that really, but I am guilty of that. You know… there’s a picture in the show of a close-up of an Ingres painting of Christ. It’s in black-and-white. But I was in the Louvre and I saw this painting; it was on loan to the Louvre. This exquisite Ingres of Christ—huge, huge painting with bold, beautiful colours. And I just wanted… I looked in my camera and there was just his head and his hand. It was like having a document, a photograph of Christ. I wanted to have that. So I took the shot.

I was in the Guggenheim Bilbao and saw this huge Twombly. And it just made me shudder. Alright, I could have bought the catalogue or something. But taking a picture of it myself, somehow… maybe it just gives me a little sliver of ownership, a shadow of ownership.

Sometimes it’s more of a sharing thing. I got to see Herman Hesse’s typewriter, the typewriter he wrote Glass Bead Game on. And sometimes I have a very unique position. I’ll do benefits or raise money for foundations that own precious objects, whether it’s Charlotte Brönte’s or Virginia Woolf’s. And in doing a benefit for them, they’re very nice to let me take something out of a glass case and photograph it. And this privileged position gives me a chance, one, of taking the photograph that I want, but also of letting other people see this object a little more naked than they would see it. First of all most people aren’t going to go up a mountain and see Herman Hesse’s typewriter, or go to Charleville and see Arthur Rimbaud’s utensils or geography book, and even if they did they’d be condemned to see it through glass. So I have this unique position to be able to photograph it and give it to the people, give it to the viewer. So it’s not all selfish!

DB: I really related to “Camera Solo” in that when I was in my early 20s and went to Europe for the first time, it was essentially a tour of graveyards, and I took so many photographs of gravestones, like Keats’ and Shelley’s in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome. I still have the photographs and don’t regret taking them but in a way, I don’t really know what they’re for.

SS: That’s the thing, you know, when I was filming Patti and learning about her, we’d always go to these graveyards.

PS: Well they’re just beautiful.

SS: They are. I used to hang out in graveyards when I lived in Milan. I’d go there on a stormy day and just sit there. So we had something in common and for me it was really refreshing to see her pilgrimage to a place where she wanted to be near that person or spirit. That was one of the things… I don’t know if we’ve ever talked about it, but it really bonded us. That spirituality, it’s wonderful.

PS: When you’re a young person, you’re in love with Keats, you read his poetry… I don’t know. For me, to go and visit someone’s resting place, you’re so close to them. They’re right under foot. You’re in proximity to someone, the same kind of feeling, you know, if your grandparents die; for me, it’s my mother, or going to see my brother. I don’t go to visit my husband’s grave to sit there and cry. I go because I saw him being buried and know he’s there. I know the spirit is elsewhere but certain aspects of him are there. And when I’m there I’m close to him. And that makes me happy. It just puts a sense of place. It helps people organize their emotions.

It’s like church. We don’t really need a church to pray; we can pray anywhere. But a mosque or a synagogue or a cathedral gives people a sense of place to organize their emotions, in order to commit the simple act of praying. A resting place does that for people. Suddenly you’re in a place and, you know, you can tell Jim Morrison, “Thank-you for your work, your music, your poetry.” You can meditate on, say, Susan Sontag or Yeats. Just like you can meditate on your brother. But sometimes when I’m in a cemetery, I might see a beautiful angel and then notice that a 15-year-old girl has died and they have placed that angel there. I just stop for a moment, and think of her.

Look at the times that we’re in. We’re in a real time of celebrity, this cult of celebrity. What’s it all about? Young people exploiting themselves online, on YouTube or whatever, seeking some kind of recognition. What is all of that? We didn’t have that. When I was younger, you wanted to be an artist because you wanted to do something great. Now, a lot of it has to do with the attention that you get. The fame and fortune. Sometimes, just the attention. What’s that all about? Simply, it’s that people feel invisible. They want to be recognized. If they can’t declare their own existence they want someone to help them declare it. They want affirmation that they’re here. And I think sociologists might be able to figure this out. Maybe it’s because parents work all the time and kids are always alone. I don’t know how our culture evolved this way.

DB: I appreciated what you said in your introduction to “Ghost Dance” at Thursday night’s performance, about the persistence of our ancestors, how they’re still with us. There’s a bit of cultural amnesia nowadays, where we don’t value history, or the passing of stories and information down.

PS: I think this disconnect happened in the 21st century. I don’t know if it was pre– or post–September 11, or if it happened with new technology, but this sense of the oral tradition, of knowing. When I was growing up I knew not only the movie stars that I liked, but all my mother’s movie stars, every movie that she liked. I could tell you about every Bette Davis film, or even before that, about Beverly Bayne, the silent film stars. And the same with rock ‘n’ roll. You know what influenced it, the entwined history, not just what’s happening in the present.

We’re very present-based right now. But we carry that knowledge. To me, it’s a beautiful thing. It doesn’t preclude revolution. Yeah, you want to, as Jim would say, break on through to the other side. You do want to tear down walls. You do want to discover something no one has discovered before. But doing that and also keeping hold of the thread attached to the kite of learning—that’s also a beautiful thing. It magnifies your efforts. Because, what is revolution without a past? What does it mean? Everything means something in relationship to everything else that is going to happen and that ever has happened. We shouldn’t lose that sense.

DB: I feel like you’ve just explained in a nutshell why you’re so enamoured of French culture—because France holds on to its history and also respects the place of revolution in that history.

PS: Yes, but also, think about the French declaration of independence. Who’d they get to help write it? Thomas Paine. An American! Of course, he was an American from England. [laughs]

I worry that I’ve done all the talking. Steven is a real artist; he is so visual. Robert [Mapplethorpe] was like that. If Robert and I would have to do an interview together, Robert would just sit back and he would look so impeccable; he’d put his hand here [gestures to her hip]; he’d have scarves here or a big thing of keys. He’d look so beautiful. And I’d just be yappin’ away. Robert was intensely visual. I’m very visual myself and relate to the visual world but it’s not my apex.

SS: Mine is visual. It’s true. We’ve talked about that before, that I’m so visual and Robert was too.

DB: Your final concert in Toronto is dedicated to Robert Mapplethorpe and marks the day of his passing. You’re clearly very ritualistic; is there something that you typically do on this day?

PS: March 9th? Well it’s a very interesting day for me. It’s a twofold day, which I will acknowledge tomorrow. March 9th was the day I met my husband. I met Fred [“Sonic” Smith] on March 9th, 1976. And Robert died on March 9th, 1989, which upset my husband for obvious reasons—that Robert would die on our special anniversary. But then Fred, in 1994, died on November 4th, which is Robert’s birthday.

DB: Weird.

SS: That happens a lot with this one.

PS: So November 4th is Fred’s passing day and Robert’s birthday, and I often do something on that day, and March 9th of course is one of the happiest days of my life—I met Fred—but it’s one of the saddest days of my life, as Robert died. Sometimes I’m just travelling; I could be in an airport just thinking. It’s strange, because I’ll flip over. Some years I’ll be thinking more of Fred. But if I have the opportunity to do a little memorial concert, I’ll do it. I’ve done a lot of them through the years, for all kinds of people: Ezra Pound, Hermann Broch, and of course Blake, Rimbaud, Jim Morrison. It gives you a focal point.

Sometimes it seems so stupid to sing 20 songs for people and leave. What is that? They could get a DJ to do that. Sometimes it’s nice to give people a structure to contemplate. And it’s not a sad structure. Tomorrow’s not going to be a sad day; it’s going to be a happy day. I met my husband on that day and my son and daughter are going to be playing with me. And Robert died 23 years ago and he’s still very present. It’s an opportunity to express my love and remembrance to these two men and also share them with the people but also give the people a template for their own process of loss. It doesn’t mean they have to give a concert but there’s no reason to put your loved ones away in a drawer because they’re gone. I like having them hang around. Jesus Christ! I mean, actually, Jesus Christ: he died 2000 years ago and we still have him hangin’ around.

SS: Literally. [Laughs]

PS: We keep him present. We keep Caligula or whoever—King Lear, Shakespeare, Abraham Lincoln, they’re all present. What I’m saying is, it’s also nature, regeneration. We don’t mourn when all the corn withers and the trees dry up and the leaves fall and the cherry blossoms die. We don’t get paralyzed. We remember them and think of them. And they return.

This interview has been edited and condensed.