One afternoon, not long after his return from the battlefields of World War II, Paterson Ewen was sitting in the sunroom of his parents’ upper-storey duplex on Western Avenue in Montreal, reading a book. A tall, handsome 21-year-old, with the athletic physique of the football star he had once been at Montreal West High, Ewen had recently enrolled as a BA student at McGill University with the vague idea of becoming a geologist. The book was George Bernard Shaw’s play The Doctor’s Dilemma, in which a doctor is forced to make a God-like decision between saving the life of a young artistic genius who is also an immoral rascal, or in effect killing him by choosing to help a decent, older, quite ordinary man.

Ewen’s mother was out. His father was wandering around with a scotch in his hand, the usual sign of trouble ahead. When Bill Ewen drank too much he tended to get feisty, even violent—if he didn’t pass out first—which invariably reduced his wife to tears and increased his son’s chronic anxiety. Paterson was having trouble enough just being back under the family roof as a grown man and a war vet, and he was exhausted by his father’s habit of waking him in the middle of the night to brag drunkenly about his contributions to the mink industry in Canada.

Ewen put down the book and went to fetch the German pistol he kept as a war souvenir in his top drawer. Passing his father in the living room, he was suddenly overcome by a wave of panic—as if all the rules of life had been taken away, as if he were free to commit any act, as if he were the one to judge who should live or die—and he fainted to the floor. He woke up in a bed with a slight fever, unable to remember his own name.

He consulted a McGill psychiatrist—“one of the tough ones,” he recalls—who sent him with a note in hand to a younger colleague at the Allan Institute. En route Ewen peeked at the unsealed note and saw himself described as a schizophrenic. But the second doctor rejected that hasty diagnosis: the panic attack, he concluded, had been provoked by Ewen’s unconscious intention to murder his father.

Paterson Ewen has never made a secret of his psychological problems or his own long bouts with alcoholism. Every profile of the 71-year-old artist, who is being honoured this fall with his second major exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario, mentions one or both; most imply a connection between them and his art. Indeed, among those who know of Ewen’s astonishing shift from hard-edged minimal abstracts to large-scale plywood Phenomena Paintings, there is a distinct impression that his artistic breakthrough followed immediately and directly from his mental breakdown in 1968—as though rain storms, lightning bolts and full moons were descriptions of his psychological agitation, the volts of electricity that had been zapped through his brain, and a graver kind of lunacy.

That fits the popular and even scholarly axiom that there is a close link between madness and the muse. Socrates proclaimed it; the Renaissance and the Romantics embraced it; Vincent van Gogh and Jackson Pollock personified it; science confirmed it. “Recent research strongly suggests that, compared with the general population, writers and artists show a vastly disproportionate rate of manic-depressive or depressive illness,” Kay Redfield Jamison stated in Touched with Fire, her persuasive examination of the issue.

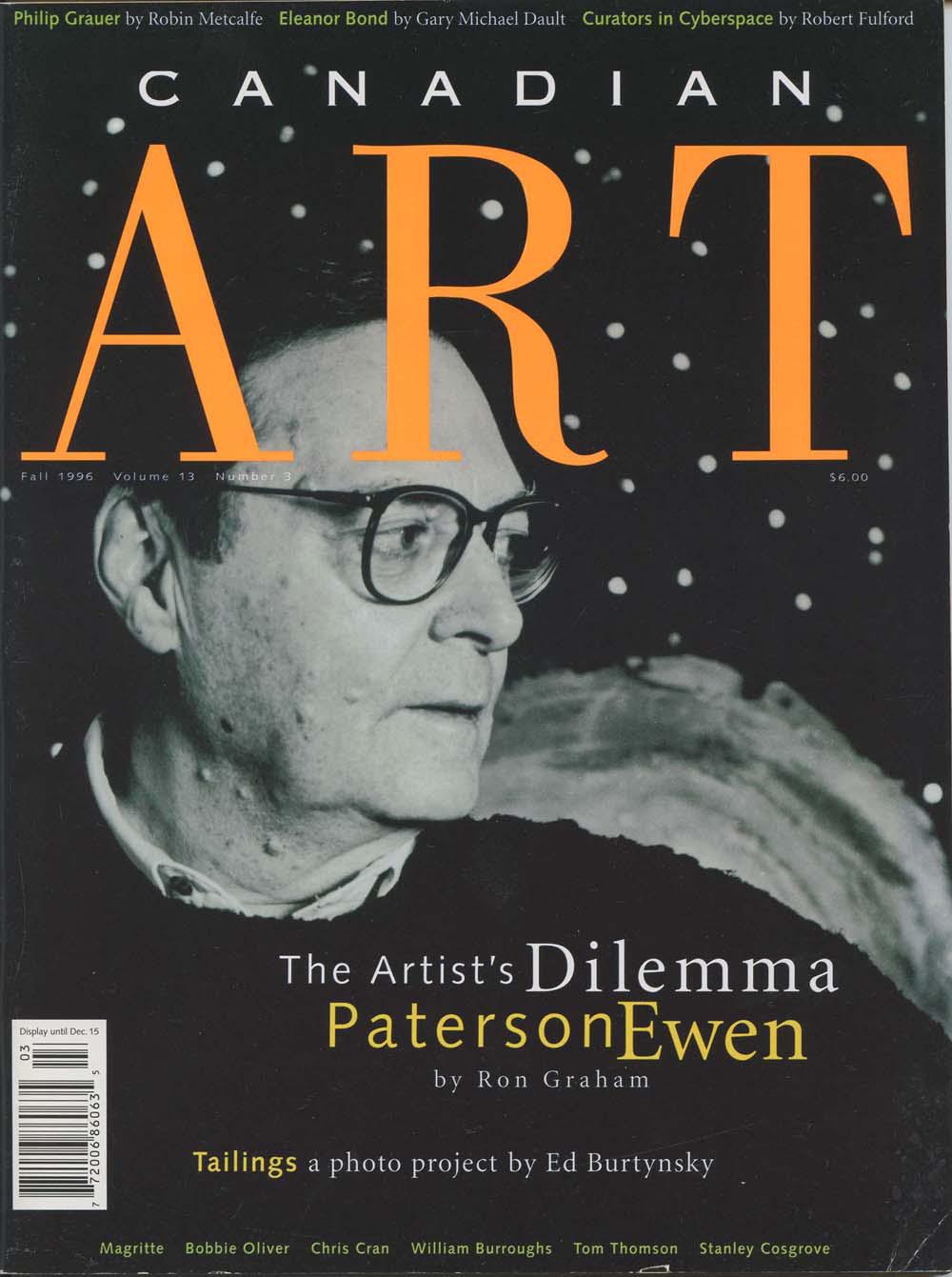

Paterson Ewen, now a heavy man of passive demeanour and subdued speech, whose eyeglasses and hearing aid add to his air of remoteness, appears to substantiate her thesis. But that only begs the more interesting question: what has been the actual effect—if any—of his illness on his art? Surprisingly, in this era of psychohistory, when thick biographies of William Blake and Mark Rothko probe the darkest recesses of their souls and the Museum of Modern Art’s 1996 blockbuster focused on Picasso’s feelings toward the women in his life, critics have shied away from investigating that question. “Who would presume to explain this man, or communicate his depths?” journalist Adele Freedman asked at the time of Ewen’s first AGO show in 1988. “Too many people play ‘What’s His Trauma?’”

Ewen himself seems ambivalent about the issue. During the dozens of hours I spent with him this past year in preparation for the biographical essay in Paterson Ewen (Douglas & McIntyre), he was remarkably forthcoming about his childhood afflictions, his love life and his hospital stays, as though he appreciated their relevance to his work. When discussing The Bandaged Man, for example, the disturbing portrait he did in 1973 from an etching in an old encyclopedia of a man almost completely swathed in bandages, he was quick to recognize its reference to his own wounds. At the same time, though he is an avid reader of biographies about artists and writers, he was dismissive of any attempt to sensationalize his personal history—“National Enquirer stuff,” he’d mutter with anger and scorn—through glib comparisons to van Gogh’s neuroses or undue emphasis on his own battles with booze.

“My Phenomena Paintings probably do express moods, but normal moods,” he insists. “They don’t have psychological overtones like Munch’s The Scream. The artists I know who are obviously quite ill don’t do much, because they don’t have sustaining periods of creativity, and I’ve never met another artist in any of the five psychiatric wards I’ve been in.”

|

|

Spread from “Paterson Ewen: The Artist’s Dilemma” by Ron Graham, Canadian Art, Fall 1996, pp 70–9 |

With Ewen’s permission, I sought out the person best qualified to discuss—or at least speculate upon—the connection between his illness and his art: Dr. Ashok Malla, former chief of psychiatry at Victoria Hospital in London, and now a professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Western Ontario, and—something not mentioned in his 25-page c.v.—Paterson Ewen’s psychiatrist since 1987. Bright-eyed and soft-spoken, casually dressed in a modish sweater and seeming more youthful than his 48 years, Dr. Malla sat in his office one day last March with a few prints from Picasso’s Blue Period on the wall and Ewen’s thick file open on his knees.

“Mr. Ewen is a classic example of someone who has had multiple psychopathologies,” he began, with the clarity of an Anglo-Indian accent somewhat flattened by 20 years in Canada. “Genetic vulnerability and a ‘bad’ environment, for want of a better word, together produced something much more severe than would have been produced with one or the other.”

In Ewen’s case, in other words, the old debate between nature and nurture hardly matters, except to the extent that each aggravated the worst in the other. His maternal grandfather was a heavy drinker who killed himself at the age of 62; one of his mother’s brothers and at least one of her four sisters suffered depressive episodes; and she herself had been treated with laudanum after breaking down from the effort of trying to teach unruly boys, almost her own age and size, in a frontier schoolhouse in Northern Ontario. Ewen’s paternal strain in no more sanguine: both his father and uncle were dour Scotsmen marked by black moods and an addiction to alcohol.

Bill and Edna Ewen carried their genetic weaknesses—likely accentuated by the sternness of their fathers and the premature death of their mothers—into their marriage. He drank and stormed; she wept and sought refuge in religion. Between his gruffness and her coldness, the predominant atmosphere in the house was one of tension. It made Paterson all the more agitated, which in turn made his mother all the more irritable.

“I guess she was disappointed about the way things were working out with this wonderful son of hers,” suggests Ewen’s only sibling, Marjorie, who has also been treated for depression. “She got pretty rough on him, just like she was with me. When she went to the doctor about all this nervous stuff, he told her she’d have to stop the heavy discipline with this kid.”

Ewen displayed worrisome symptoms from an early age. When the son of a family friend approached his crib and gave him a few metallic toy trucks, the smell of the rubber wheels made him scream hysterically. As a boy he suffered from what the family doctor diagnosed as St. Vitus’ dance, which caused his eyes to roll uncontrollably, and he was pulled from school for a year when his face and shoulders erupted in massive tics. He was handicapped, moreover, by dyslexia and shortsightedness, neither of which was detected until long after they had damaged his self-esteem.

His abnormal nervousness as a child is not incidental to what happened to him as an adult,” Dr. Malla said. “The tics, the dyslexia are manifestations of an overall neural vulnerability—perhaps a lack of maturation in certain aspects of the brain. We don’t know enough to be more precise. Not everyone with dyslexia develops depression, but they are prone to all kinds of mental disorders.”

|

|

Spread from “Paterson Ewen: The Artist’s Dilemma” by Ron Graham, Canadian Art, Fall 1996, pp 70–9 |

In June 1946, when Ewen sailed home after 18 months overseas and took the train from Halifax to Montreal, he found his family waiting in the “E” section at Windsor Station. “I dropped my duffel bag and embraced them,” he remembers. “I could feel my parents stiffen up, as though they were going to have a fit or something. If my sister hadn’t burst out crying and thrown her arms around my neck, I might not have stuck around.”

Strangely enough—or not, if you’re a psychiatrist—recognizing the urge to kill his father seemed to make things better rather than worse for Ewen. “Part of me did hate him for the life he gave my sister and me,” he says, “plus all the aggravation he was causing me at night. But I left the pistol in the drawer, and I never felt quite the same anger towards him again.”

In its aftermath, as well, Ewen began drifting toward his calling and salvation. Except for Grandfather Ewen’s semi-professional talent as a sculptor and his own childhood delight in shaping wax figures, he had not been exposed to art at home or at school. Following his first year at McGill, however, he taught himself how to draw and paint. Such was his pleasure in it that he signed up for John Lyman’s drawing class on his return to university. Halfway through the year, he transferred to the School of Art and Design at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, then under the direction of Arthur Lismer. There he took a wide range of art courses and fell under the sway of Goodridge Roberts.

Like Roberts, who himself was under psychiatric counselling for depression, Ewen found in painting both an emotional outlet and a therapeutic release. His first landscapes, still lifes and portraits were noteworthy for what an early critic called “the brutal way he painted” and a later one described as “a brushy nervousness and an anxious sensibility.” John Bentley Mays, the Globe and Mail’s art critic, looked at a watercolour Ewen had done in 1950 of an empty field in Montreal West and was struck by “its anxiety, its brooding greens and browns, its strange tone of dejection and abandonment.”

“There was a sense of danger about him,” remembers Vancouver artist Sylvia Tait, who won the top prize during their year at the art school, “and part of it was his strong aura of sexuality.”

Though he was a “fine-looking” man, as Tait put it, Ewen was still a virgin when he returned from the war. The product of a highly repressed environment and his own adolescent insecurities, he was actually too shy to press for a first dance, date or kiss. Once, overseas, when he finally mustered the courage to kiss a beautiful Dutch girl he had been seeing, she immediately dragged him by the hand to her house and roused her parents out of bed. Her father asked Ewen his religion and was pleased to find in a book that the United Church of Canada was Protestant. The kiss had meant more than Ewen desired it seemed, and it took 3,000 miles of ocean and a dwindling correspondence to break the engagement.

His prospects improved in Lyman’s class, where Ewen was the only male student among 64 young women. One of them, the 17-year-old daughter of a Yiddish poet, became his lover, and her gentleness had such a calming effect on his nerves that he almost married her. Instead, he accompanied her to a lecture given by a beautiful, free-spirited French-Canadian artist and dancer named Françoise Sullivan. It wasn’t long before Ewen and Françoise were sneaking into her parents’ apartment on Peel Street for passionate afternoon trysts. Once, when her father surprised them by coming home unexpectedly, Françoise quickly shoved her lover into a hall cupboard, where he spent an hour sitting naked among the galoshes with a book about William Blake.

Ewen’s marriage to Françoise, the birth of their four sons and a series of nine-to-five managerial jobs coincided with nearly two decades of relative stability. Money was always tight; Françoise was often out working on her dance career; their first child, Vincent, was born with serious developmental problems; Bill Ewen and his daily bottle of scotch moved in with them after Edna’s death in 1951. But Ewen bore his domestic responsibilities stoically, made time late at night and on weekends for his art, and didn’t feel the need to seek more psychiatric help. “He was a good husband, a good provider, good with the children,” says Françoise. “I had nothing to complain about.”

He only collapsed, indeed, after their marriage fell apart in 1965. Françoise had fallen in love with Frank Scott, the brilliant and charming poet, professor of constitutional law at McGill, cofounder of the CCF (NDP), and husband of the artist Marian Scott. Françoise refused to drop him despite Ewen’s threat to leave. Their separation prompted—if it wasn’t in part prompted by—a sort of midlife crisis. He turned 40 that year, he seemed stalled as a minor Montreal artist, and he had ricocheted into an affair of his own with the psychologist Stephanie Dudek. Unhappy, angry and increasingly drunk, he once accidentally broke her leg in an aggressive bit of tomfoolery at a party. Their relationship did not last long. Alone in a small house in a working-class district during the summer of Expo 67, he experimented with drugs, was fired from his personnel job with RCA Victor, and spiralled downwards into anxiety and depression.

|

|

Spread from “Paterson Ewen: The Artist’s Dilemma” by Ron Graham, Canadian Art, Fall 1996, pp 70–9 |

In the spring of 1968, Ewen entered Queen Mary Veterans Hospital in a somewhat hysterical condition and was tranquillized into a semi-coma with shots of insulin. “Chronic anxiety disorder is no ordinary anxiety,” Dr. Malla explained. “It’s an anxiety that literally would drive you crazy. When Mr. Ewen’s in that state, you could hardly imagine he’s the man who could do this wonderful art. I’ve never seen anyone become as severely agitated, to the extent that he is not able to function. He can’t sit still for even two minutes. That is the most disabling problem, more than depression, though they’re closely related.”

A few months later, while living in the basement of his sister’s house in Kitchener, he plunged into a darkness that sent him to the Westminster Veteran’s Hospital in London for eight months. There he submitted to the first of a series of electroshock treatments, which erased parts of his memory but left him feeling better than ever. “I came out of there in a very, very good state of mental and physical health,” he remembers.

It did not instantly alter Ewen’s art, however. When he emerged from the hospital and moved into a studio on Richmond Street in downtown London, he picked up where he had left off, except for giving his minimal lines a more active and expressive swoop. It wasn’t until some two years later that he abandoned canvas, first for sheets of galvanized iron and subsequently for plywood boards. One day in 1971, for no evident reason, Ewen conceived of producing a series of gigantic prints of the sun’s corona by gouging deep cuts into a four-by-eight-foot piece of plywood and applying paint to its surface. Midway through the process he had a brilliant flash that the gouged and painted board was itself the final work. Only then, after more than 20 years of toiling in the vineyards of figurative and abstract painting, did he discover the medium, the theme and the scale that would become his signature style.

That dramatic inspiration will forever remain one of the happiest, yet mysterious, developments in Canadian art history. For many, even Ewen sometimes, his breakdown seemed the most obvious explanation. “Around that time,” says Ron Brenner, one of a score of young London artists Ewen has befriended and helped over the years, “there was a whole group moaning about how depressed they were, how badly things were going. Pat joked, ‘Why don’t you try having a nervous breakdown? That’s what got me going.’”

John Bentley Mays, himself a victim of severe depression and the author of an acclaimed book on the subject, concurred. “Ewen seems to have been one of those victims of what psychiatrists call ‘benign psychosis,’” he wrote in 1982, “a disorder that rips a person apart, but leaves him at a higher level of personal and creative integration than he could have achieved before the illness.”

Ewen’s breakdown may have released the primitive wonder and excitement he had felt as a child gazing through his telescope at the stars (and at a female neighbour undressing in her front window) or magnifying postcards and pin-up girls on the wall with his slide projector. Or it may have opened a channel to the same cosmic energy that Ewen admired in Turner’s seascapes and Constable’s clouds. (Is it mere coincidence, for example, that Turner was a depressive, Constable an alcoholic, or that Ewen becomes noticeably shaky on full-moon days and once wrote a poem to “that cold eye in the sky”?) But Dr. Malla, for one, had his doubts.

“There may be something to that idea, but I don’t think there’s much of it with Mr. Ewen,” he said. “An experience of a different level of consciousness may add to your creativity. Even if you have only partial memory of it, you may be able to recreate something that you normally wouldn’t have experienced. But, after talking with Mr. Ewen over the years about his interest in planets and weather and so on, it seems to me it’s very much a conscious intellectual interest, often taken from books, rather than some weird experience he’s had. As far as I’m concerned, his illness has been an impediment to his creativity. It’s no different than if he had heart disease.”

What really got Ewen going was the change his breakdown made to his circumstances. He was liberated from the tensions with Françoise and the demands of raising a family; he was living with the artist Jamelie Hassan, whom he had met in 1969 at a students’ party; he was earning a regular paycheque teaching painting at H.B. Beal Secondary School (and was freed from that when he got a Canada Council A grant in 1971–72); and he had already had a couple of successful exhibitions in London. He felt so free and confident, in fact, that he called this his Fuck You period.

After years of following the trends in the international art world and the highly politicized Montreal scene, he had arrived at a dead end with minimal abstraction and was bored. Nor was he alone. The example of the American artist Philip Guston, for one, inspired him to give up on the prevailing fashions and do whatever he thought interesting, satisfying and fun. Experimentation and anti-art art were in the air, moreover, and London was especially open to variety and innovation.

Ewen cannot explain why his sense of freedom expressed itself in suns, moons, constellations, comets, oceans, storms and other natural phenomena. The images he happened upon at the time in old scientific texts were clearly influential, as was Frantisek Kupka’s spiritualist abstract The First Step, which Ewen had admired on his visits to New York. But it is equally clear that his phenomena were neither the result of psychotic or drug-induced visions—he has never even painted when drunk—nor a literal expression of his torments. (He tended to save that for his rare self-portraits or such unusually symbolic paintings as Ship Wreck and Right-Angle Tree.) And though his paintings are marked by vivid colours and aggressive gestures, he didn’t have van Gogh’s hysteria.

|

|

Spread from “Paterson Ewen: The Artist’s Dilemma” by Ron Graham, Canadian Art, Fall 1996, pp 70–9 |

“I never had a manic side,” Ewen says. “I just went from depressed to normal. When I was depressed, I did bright paintings, I heightened everything, as if the sunshine were trying to get out from the depths below. The paintings I did on an even keel are more subtle.”

“When he’s really depressed, he can’t pick up a pencil,” Dr. Malla added, “and when he’s well, he doesn’t have the kind of creative bursts that van Gogh has. He’s just stable and continuously productive.”

The critical and commercial success of the plywood works, coincident with his appointment as a painting teacher at the University of Western Ontario in 1972, seemed to initiate another long stretch of stability and productivity. Says artist Lynn Donoghue, who lived with Ewen for several months in 1973 when she was 20, “He was 48, as poor as shit, but he believed in painting, it meant something to him, and he made us all feel that it was a real thing to do.”

Though he spent many an afternoon and evening in bars like the York and the Clarendon, was prone to jealous tantrums if someone paid too much attention to Hassan or Donoghue, and became known as a street fighter because of a couple of drunken punch-ups, he worked hard to prepare for his regular exhibitions at the Carmen Lamanna Gallery and did his teaching job well. By the end of 1980, he had settled comfortably into a large Victorian house on Maitland Street with one of his former students, Mary Handford. They travelled to Europe, Bermuda and the Arctic and celebrated the big prices his Phenomena Paintings had started to fetch by riding around town in a new blue Cadillac. But, just when his life and psyche seemed to be back in order, they shattered once again—from an entirely different cause.

All this time, it turned out, Ewen was actually being held together by a daily intake of alcohol, Valium and lithium. In July 1986, Mary, fed up with his boozing, went off to become an architect.

Bitter about her, and on his own once again, Ewen sold the house on Maitland Street and moved into an old factory behind the U-Need-A-Cab stand on a derelict stretch of Dundas Street East. It was the year he did his renowned self-portrait, a disquieting study of suppressed anger and hurt, based on several photographs of himself standing in a corduroy suit and striped tie. “I didn’t see it for years afterwards till I came across it hanging in the National Gallery,” he says. “Only then did I realize how grim I looked in my face and attitude.”

When he wasn’t painting or teaching he drank, until the day late in 1986 when he blacked out on the street. He checked into Homewood, an addiction treatment clinic in Guelph. There he was pulled cold turkey, not just from alcohol, but from his heavy medication, too. He immediately slipped into acute depression and, for the first time, developed paranoid delusions. He imagined that water had flooded up to the height of his bed, for instance, and that he was carrying a highly infectious disease capable of killing whoever touched him. It was one of the very few occasions he seriously considered suicide.

“It is very important to understand that most of his psychotic episodes were related to the withdrawal from drugs,” Dr. Malla said. “He doesn’t have a psychotic illness as such, but his depression is as severe as any psychosis can get, and he did have the worst benzodiazepine withdrawal I have seen in my career. When it wasn’t terrifying, it was quite fascinating. At one point, I remember, he said he was hearing one of Samuel Beckett’s plays directly from Dublin through his pillow. It took us about a year to come to understand that he had a chronic anxiety disorder and a recurring depressive disorder, plus a tendency to become addicted to alcohol and benzodiazepines. In his case, the three go together: they are genetically and otherwise connected.”

Shortly after Ewen returned to his studio in June 1988, Mary Handford phoned to say hello, and he invited her to visit. They saw each other from time to time over the next year, and in August 1989 she moved back to London. Two months later they bought a handsome home near the university, at the north end of Wellington Street, from which he set off most mornings for his studio, and they resumed their holidays in Europe and Bermuda. In January 1992, however, he crashed again when he was rushed to hospital with a twisted bowel and shifted to intravenous doses of his tranquilizers and antidepressants. It took him more than nine terrible months to get back to normal.

Ewen hasn’t had a relapse since then. He takes his pills religiously; he forswears alcohol; he doesn’t even read the morning paper anymore in case something upsets him. Indeed, though age and illness have sapped some of his legendary fortitude and physicality, compelling him to sometimes take long afternoon naps at home and occasionally employ an assistant at work, he has been especially productive—both in terms of output and imaginative growth. Besides his spectacular suns and moons, he’s done a wonderful series of small works on steel with painted frames, several minimal works of bands of colour swirling across unpainted plywood like the trail of something spinning out of orbit, and two bold, Matisse-like portraits of nudes painted in resplendent Expressionist colours.

“Matisse said something to the effect that the idea is not so important, it’s the doing of it that’s important,” Ewen concludes. “And Picasso took that further, as usual, by saying that the idea is nothing, it’s all in the doing. I start out thinking that a painting is going to be like this, with this line or this yellow, and it never turns out like that at all. I get excited working with the colours and forms and textures; I play with them, and the original idea disappears completely. I have no interest in pinpointing how or why. I just hope to have an experience that will eventually be an experience for other people.”

As though to symbolize the fresh start, Ewen married Mary Handford, and this year they moved into a bigger, brighter hilltop house and studio—part Mediterranean villa, part West Coast modern—with all-white walls, a three-storey expanse of windows overlooking a parkland panorama, space enough for four major Ewens in the living room and a studio on the ground floor. It’s such a startling contrast to the dark and dingy factory in east London that Mary herself worried whether the move would destabilize Ewen. On the contrary. “Now that I’ve seen how he’s gone through this,” she says, “I don’t think there’ll be a problem with all the attention this fall.”

With the AGO show in September, an exhibition of new works at the Olga Korper Gallery in October and the publication of a book about his life and work, Ewen will face another barrage of media interest in his breakdowns and alcoholism. When all’s said and done, however, he will be where he’s always been: in his studio, with his router and his brush, grappling once more with the phenomenon that remains beyond his own or Dr. Malla’s comprehension—as wondrous and, ultimately, as inexplicable as the comets and constellations—his artistic inspiration.

|

|

Paterson Ewen on the cover of Canadian Art, Fall 1996 / photo Don Vincent courtesy Bernie Vincent |