There was a whole lot of love in Museum London on December 1. It was directed to the memory of chief curator emeritus Paddy Gunn O’Brien, who passed away on October 4, 2012. Paddy served the London Regional Art Gallery—now Museum London—for 38 years, and the arts community for many more after that. Few in the curatorial profession in Canada can boast this length of service.

I worked with Paddy in London from 1986 until she retired in 1990, and then I went to Oakville Galleries a year later. Our working relationship didn’t stop with her retirement, or with my move away from London. Paddy edited my texts and those of my colleagues at Oakville Galleries and Museum London for another 20 years. I was under her spell for a long time.

Born in England in 1929, Paddy began her employment with the London Regional Art Gallery in 1952 (it was then a department of the London Public Library). It was largely due to her efforts that the gallery became a major force in Canada with a remarkable permanent collection. During her tenure with the gallery, she was directly involved in curating some 1,280 exhibitions. However, for Paddy it was never about quantity: it was about the excitement of connecting with artists, exchanging innovative ideas and sharing that exhilaration in an accessible way with a wider public.

In the 1950s, Paddy was a pioneer in Canadian exhibition-making. While she studied art in England, there was an absence of publications from which to learn about milestone exhibitions or the history of curatorial practice. She came to her position as an amateur—intuitively developing close relationships with artists and writers, devising critical paths and eventually viewing “the exhibition” as a medium unto itself. As a mentor to Matthew Teitelbaum and myself (I followed him as curator of contemporary art), she passed on her vast knowledge—and though she wasn’t easy on us, we can both declare that Paddy was the best teacher we ever had.

Over her long career, Paddy demonstrated remarkable resilience despite the ever-changing and challenging economic times. For her, curating in hard times was an incentive for clarifying priorities and articulating values. She always placed a positive spin on matters, being an incurable optimist. As artist Thelma Rosner commented in her tribute to Paddy on December 1, ” [In the 1970s…] she had to deal with a chaotic bunch of wilful and volatile artists on the one hand, and rather conservative administrators of this institution on the other. So far as I could tell, she navigated this treacherous road with dignity and clarity, before and after the museum’s move from the second floor of the London Public Library to this place, at the forks of the Thames. Through the parade of many directors, she remained a constant source of stability and security.”

Paddy had been at the centre of the most productive and exciting years for London art-making. In a 1969 article in Art in America, Barry Lord (then an art critic) described London, Ontario, as an art phenomenon and as “the most important art centre in Canada and a model for artists working elsewhere, the site of ‘Canada’s first regional liberation front.’” Paddy was there to champion artists such as Jack Chambers, Greg Curnoe, Tony Urquhart and Margot Ariss, as well as another generation that included Jamelie Hassan, Thelma Rosner and Wyn Gelenyse, among a thousand others.

She well understood artists and their needs primarily because she was an accomplished artist herself. Her paintings often referenced her native England and her family. But her favourite subject was Lake Huron. Paddy captured Huron’s variables of atmosphere and light in a way that came close to rivalling Chambers. To do a studio visit with her was pure joy as she bounced around full of enthusiasm, ideas and self-challenges.

As an editor, Paddy’s interpersonal skills brought out the best in each writer. Once when I asked her to massage my words gently, she replied that she had to do violence first. I wish I had kept the marginalia penned in her distinctive, neat handwriting; her notes about split infinitives—and the lashings that came with them—were uproariously funny, and you would surely remember them for the next time you submitted. Paddy claimed that her income from editing was what kept her in paint and canvas. (I, however, would beg to differ, for she donated much of her editorial earnings back to various galleries.)

Only last year, at the age of 82, did Paddy resign from her editorial career, claiming that she didn’t think she was mentally sharp enough to carry on. After a rather difficult phone call with her, I was struck with terror. I could never trust anyone with my words in quite the same way that I trusted them with Paddy.

Her concerns for the social welfare of the London community went beyond the realms of visual art. In 1963, Paddy ran federally as the NDP candidate for London. She didn’t win the seat, but she won lots of friendships in the process. Not being elected didn’t change the significance of her passions, her abilities or her dreams: it merely enhanced her plans.

Paddy had an incandescent passion for learning, a strong moral compass, intellectual curiosity and a deep respect for artists and cultural workers. She always stressed the importance of excellence, accessibility and optimism. This is what her long career embodied. I realize now how acutely I will miss Paddy’s presence in the world—her phenomenal energy, wise counsel, generosity and keen sense of humor.

To quote Paddy’s favourite poet, Rainer Maria Rilke, “A person isn’t who they are during the last conversation you had with them—they’re who they’ve been throughout your whole relationship.” Paddy was my dear friend, my sweet mentor. Until the end, the landscape inside her was vast, complex and irrepressible.

Marnie Fleming is curator of contemporary art at Oakville Galleries.

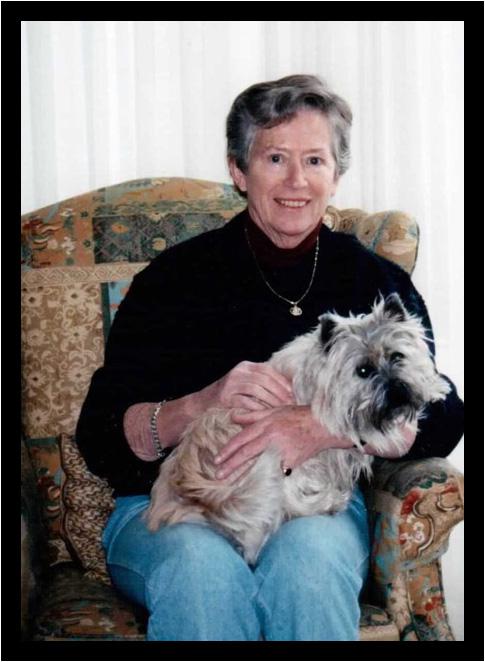

Paddy O'Brien / photo courtesy Judith Rodger

Paddy O'Brien / photo courtesy Judith Rodger