Nuit Blanche Toronto begins at 6:58 p.m. this Saturday, October 1, with nearly 90 independent projects by Toronto’s art community and four city-curated exhibitions featuring 48 other projects, all by some 300 local, national and international artists.

It’s impossible to see everything—and also impossible to know, given the event’s ephemerality, what art will have the most impact. Here are seven projects our editorial team will be sure to see.

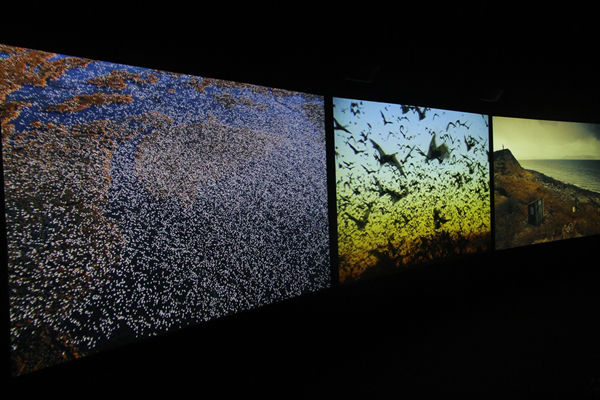

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea (installation view), 2015.

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea (installation view), 2015.

John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea at the Design Exchange, 234 Bay Street

During the press week for the last Venice Biennale, the art world gathered, cross-legged, around these three-channel images of aestheticized global plundering, extraction and movement as if they were some perverse hearth. John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea is ideally experienced with a crowd: and, though Nuit Blanche lines are notoriously long, I hope as many Torontonians get to see it this way as possible. It’s a postcolonial opus, partly inspired by Moby-Dick, and functioning as a contemporary World’s Fair—windows looking out on capitalist humanity’s tragic attempt to wrap its jaws around nature. (Akomfrah discusses the work with Shauna Levy at the Design Exchange before its screening on Saturday, from 5:30 to 7 p.m.)—David Balzer, editor-in-chief

Rebecca Belmore, 2016. Photo: Canada Council for the Arts / Martin Lipman.

Rebecca Belmore, 2016. Photo: Canada Council for the Arts / Martin Lipman.

A New Project by Rebecca Belmore at the Art Gallery of Ontario, 317 Dundas Street West

Details are scant in regards to Rebecca Belmore’s performance at the Art Gallery of Ontario, which of course makes it all the more intriguing. What we do know is that it’s durational—apparently a gruelling 12 hours—and that it’s a brand-new piece, commissioned to kick off the performance series running as part of “Toronto: Tributes + Tributaries, 1971-1989,” a new exhibition at the AGO curated by Wanda Nanibush.

We know another thing, too: the exhibition title refers to the buried waterways of Toronto, and its similarly buried histories. Nanibush has dug out many seminal experimental works (mostly video-, installation- and performance-based) from the AGO’s collection to fill up the gallery’s fourth floor.

We also know, from past experiences, that Belmore’s courageous and provocative performances can get physical, messy and violent—see documentation on Belmore’s website of Tent City (2004), Vigil (2002) and Bury My Heart (2000).

Nanibush was generous enough to divulge a few more clues as to what we can anticipate: she told me that Belmore will perform in Walker Court, responding intuitively to the space as both a colonial space and as an Anishinaabe space, and that her performance will honour Robert Houle, who has been staging interventions there for years, beginning with a response to Lothar Baumgarten’s blunderous Monument for the Native People of Ontario, commissioned by the AGO in 1984. Houle’s Seven Grandfathers, a series of seven ceremonial drums, preside in a ring around Walker Court presently.

Though we can’t be sure of exactly what to expect—Belmore herself won’t even know until she enters the space—I’m certain that this will be a profoundly affecting event that will linger in the minds of all those who witness it. I’m going to make sure I’m one of them.—Rosie Prata, managing editor

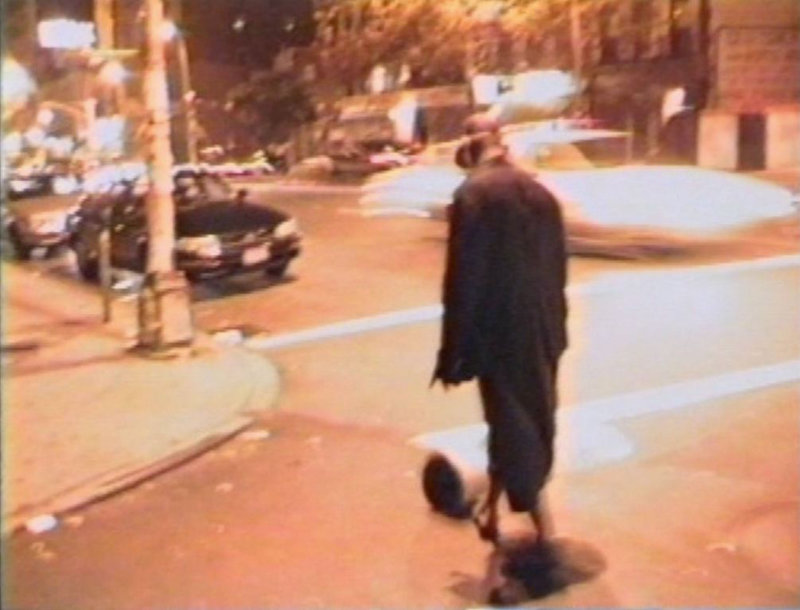

David Hammons, Phat Free (still), 1995/99.

David Hammons, Phat Free (still), 1995/99.

David Hammons’s Phat Free at Union Station’s West Wing, 65 Front Street West

David Hammons rarely exhibits and rarely makes art. He’s “elusive,” or “difficult,” depending on your vantage point, and his works flaunt convention. They are snowballs for sale, or collected chicken wings on rugs or fur coats dripped with paint. In Phat Free, Hammons records a performance in which he walked down darkened city streets kicking a metal bucket—a move by turns cacophonous and percussive.

In a way, the piece represents Hammons’s process itself—the artist roaming the city, finding material in unexpected places, confronting racism and insisting on the cultural significance of the streets. Not that Hammons cares about convincing the art world of the latter. “The art audience is the worst audience in the world,” Hammons once said. “It’s overly educated, it’s conservative, it’s out to criticize not to understand, and it never has any fun.” He may have meant this as an insult, but I’d rather take it as a challenge.—Caoimhe Morgan-Feir, associate editor

Arturo Duclos, Fallen Flags (rendering), 2015.

Arturo Duclos, Fallen Flags (rendering), 2015.

Arturo Duclos, Utopia’s Ghost (Fallen Flags) at John Street and Stephanie Street

From the relative calm of Canadian streets, it can be easy to forget that history is built on the violence of revolution. And behind every revolution lies a kind of radical utopianism driven by a volatile mix of poverty, disenfranchisement and doctrine. But utopia is literally “no place,” and not all revolutions succeed. In Utopia’s Ghost (Fallen Flags), Chilean artist Arturo Duclos carpets a stretch of Stephanie Street, just south of Grange Park, with the flags of failed Latin American revolutionary movements. It’s at once a counter-narrative of political and social ideologies that promised to rise against the status quo and a visual reminder of how the easily and quickly the ideals of equality and subversion can be relegated—underfoot—to the dustbin of history.—Bryne McLaughlin, senior editor

Philip Beesley, Ocean (artist rendering), 2016. © PBAI.

Philip Beesley, Ocean (artist rendering), 2016. © PBAI.

Philip Beesley’s Ocean at Toronto City Hall, 100 Queen Street West

The impending doom of American politics appears to have resonated with curators Janine Marchessault and Michael Prokopow, who follow their 2012 Nuit Blanche contribution “Museum for the End of the World” with a second instalment: “OBLIVION.” The project features three post-apocalyptic themed works by directors Floria Sigismondi and Director X, though Toronto-based architect and third member of the cohort Philip Beesley presents a more optimistic vision of the end. The primordial landscape of Ocean builds on Beesley’s extensive interactive hybrid textiles that have appeared everywhere from the 2010 Venice Architecture Biennale to runways in Paris. The project promises a responsive and immersive scene, destabilizing the divides between man and man-made, more Avatar than Mad Max. The artificial ocean, composed of intricate electronic sensors and recycled fabrics, is an uncanny reminder of the relative artificiality of our own water bodies filled with bottle caps and plastic bags. As debates continue over the controversial Kinder Morgan pipeline expansion, it seems like an appropriate time to reconsider the ocean, if only for a night.—Evan Pavka, editorial intern

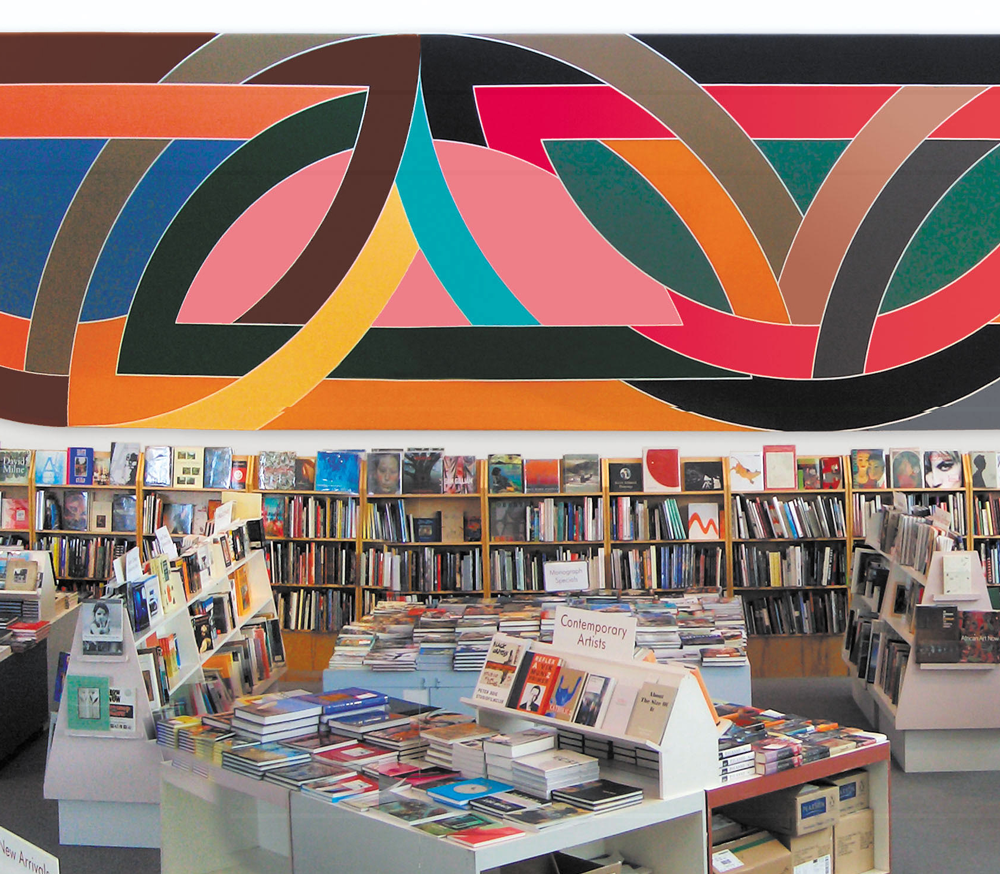

Kelly Jazvac, Browsing, 2016. Photo: Rick Simon.

Kelly Jazvac, Browsing, 2016. Photo: Rick Simon.

Kelly Jazvac’s Browsing at David Mirvish Books, 596 Markham Street

Toronto still mourns David Mirvish Books: the unusual, two-storey, theatrical round space (a former gallery for post-painterly abstraction), the Stella mural, all those rare, essential theory, literature and art books. Artist Kelly Jazvac used to work there, an education in and of itself, and for Nuit Blanche returns to present her clever signage sculptures, animated by industrial fans. Some of the best Nuit Blanche projects of late have commented on gentrification; here, art makes a poetic, haunting return to where it seems to belong.—David Balzer, editor-in-chief

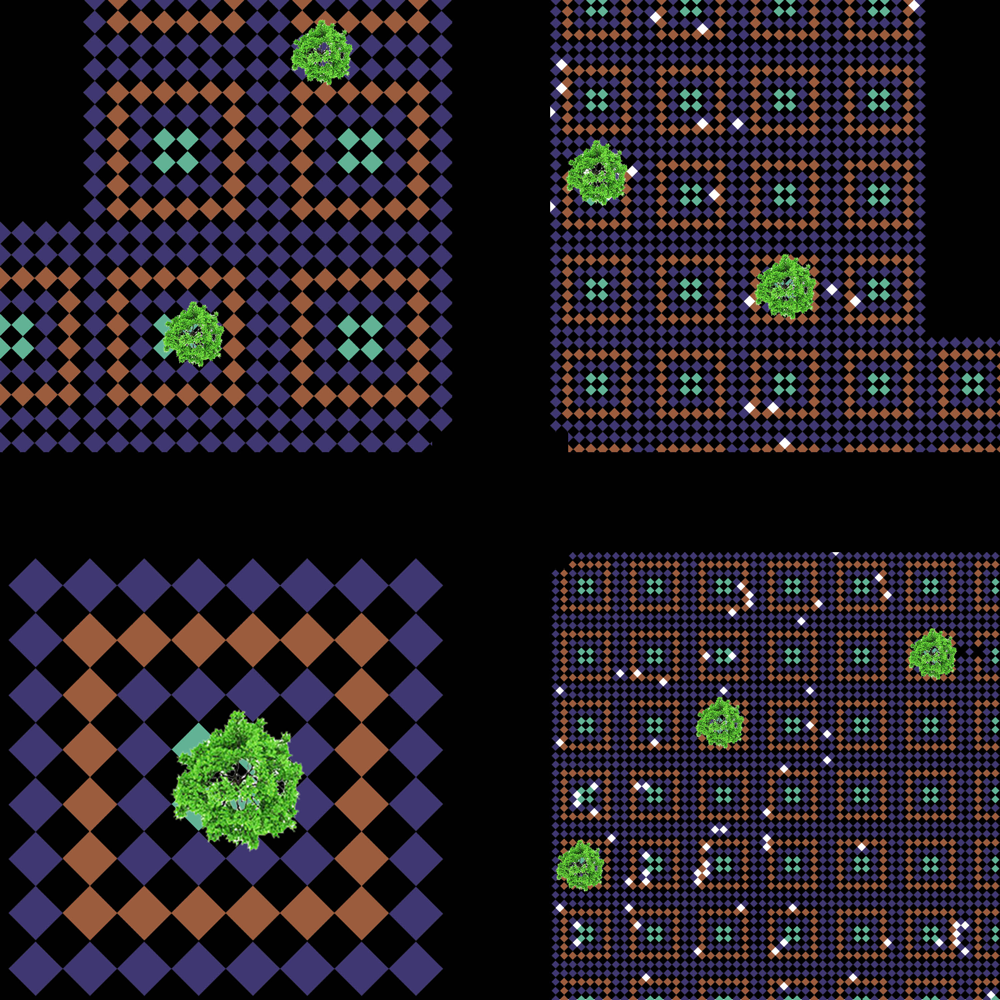

Faisal Anwar, CharBagh (rendering), 2016.

Faisal Anwar, CharBagh (rendering), 2016.

Faisal Anwar’s Charbagh: A Sensory Garden, 77 Wynford Drive

When Faisal Anwar reimagines the trimmed edges of Chahrbagh-e-Abbasi or the compartmentalized flowerbeds spreading before the Taj Mahal in Charbagh: A Sensory Garden, his latest installation at the Aga Khan Museum, the ancient garden is not so much a relic of Mughal ancestry as it is a site of data transfer, a room for millennial interaction across digitized hues, drained and leaked. As a new-media artist, Anwar is fascinated by the bleaching of colour, the dilution of it, its aging and departure from the moving image. He looks at colour’s relationship with both viewers and performers as they navigate historical memory with myth.

Drawing from his preoccupation with glitch video in the statuesque A Feast in Exile (2010) (co-created by Tazeen Qayyum) and the yellow, lyrical Oddspaces at Nuit Blanche that same year, the screen projection embraces the historicized spaces demurely, populating them with elements of the digital, both continuous and GIF-like. Here, he illuminates the facade of the Aga Khan Museum with a rendition of the Persian-style quadrilateral, historically segmented into four blocks by way of walkways or water channels, as a site of possibility after colour weathers (not by age, but by reel use, by digital repetition). This is glitch art that allows, even encourages, viewers to tweet, post and Instagram their reflections—visual or not—of the charbagh across social media. In an imaginary often sentimentalizing South Asian architecture with exoticized nostalgia, Anwar’s visuality charts the garden, a domestic paradise of bygone years, as effectively void of ornament, off-coloured, and perhaps in that removal, not so distant.—Aaditya Aggarwal, editorial intern, online

JR's projections onto city structures were a highlight of Nuit Blanche 2015. What will be the top works this year? Photo: City of Toronto.

JR's projections onto city structures were a highlight of Nuit Blanche 2015. What will be the top works this year? Photo: City of Toronto.