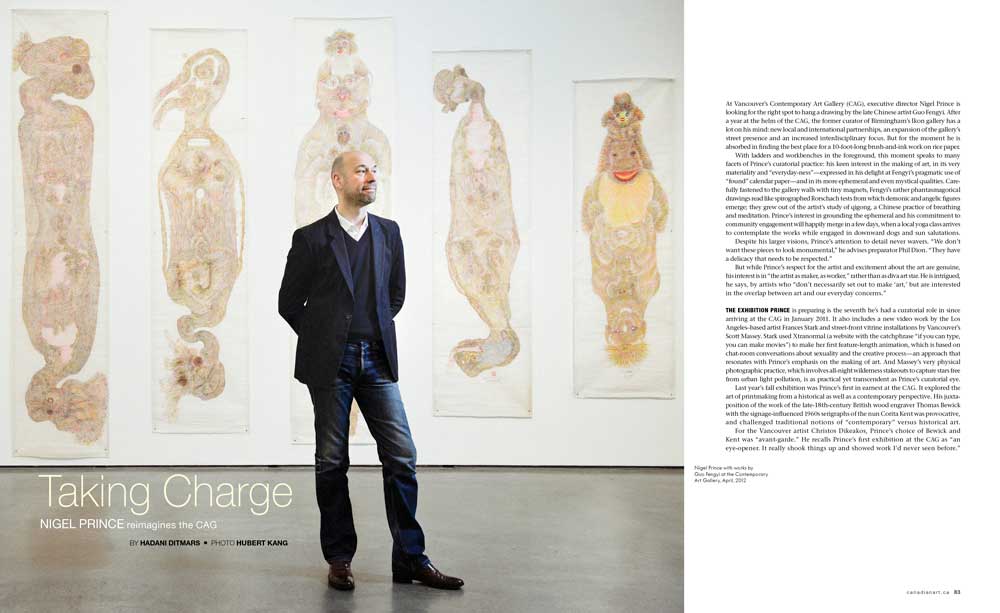

At Vancouver’s Contemporary Art Gallery (CAG), executive director Nigel Prince is looking for the right spot to hang a drawing by the late Chinese artist Guo Fengyi. After a year at the helm of the CAG, the former curator of Birmingham’s Ikon gallery has a lot on his mind: new local and international partnerships, an expansion of the gallery’s street presence and an increased interdisciplinary focus. But for the moment he is absorbed in finding the best place for a 10-foot-long brush-and-ink work on rice paper.

With ladders and workbenches in the foreground, this moment speaks to many facets of Prince’s curatorial practice: his keen interest in the making of art, in its very materiality and “everyday-ness”—expressed in his delight at Fengyi’s pragmatic use of “found” calendar paper—and in its more ephemeral and even mystical qualities. Carefully fastened to the gallery walls with tiny magnets, Fengyi’s rather phantasmagorical drawings read like spirographed Rorschach tests from which demonic and angelic figures emerge; they grew out of the artist’s study of qigong, a Chinese practice of breathing and meditation. Prince’s interest in grounding the ephemeral and his commitment to community engagement will happily merge in a few days, when a local yoga class arrives to contemplate the works while engaged in downward dogs and sun salutations.

Despite his larger visions, Prince’s attention to detail never wavers. “We don’t want these pieces to look monumental,” he advises preparator Phil Dion. “They have a delicacy that needs to be respected.”

But while Prince’s respect for the artist and excitement about the art are genuine, his interest is in “the artist as maker, as worker,” rather than as diva art star. He is intrigued, he says, by artists who “don’t necessarily set out to make ‘art,’ but are interested in the overlap between art and our everyday concerns.”

The exhibition Prince is preparing is the seventh he’s had a curatorial role in since arriving at the CAG in January 2011. It also includes a new video work by the Los Angeles–based artist Frances Stark and street-front vitrine installations by Vancouver’s Scott Massey. Stark used Xtranormal (a website with the catchphrase “if you can type, you can make movies”) to make her first feature-length animation, which is based on chat-room conversations about sexuality and the creative process—an approach that resonates with Prince’s emphasis on the making of art. And Massey’s very physical photographic practice, which involves all-night wilderness stakeouts to capture stars free from urban light pollution, is as practical yet transcendent as Prince’s curatorial eye.

Last year’s fall exhibition was Prince’s first in earnest at the CAG. It explored the art of printmaking from a historical as well as a contemporary perspective. His juxtaposition of the work of the late-18th-century British wood engraver Thomas Bewick with the signage-influenced 1960s serigraphs of the nun Corita Kent was provocative, and challenged traditional notions of “contemporary” versus historical art.

For the Vancouver artist Christos Dikeakos, Prince’s choice of Bewick and Kent was “avant-garde.” He recalls Prince’s first exhibition at the CAG as “an eye-opener. It really shook things up and showed work I’d never seen before.”

Tempered by Federico Herrero’s site-specific large-scale mural of colourful geometric forms commissioned for the CAG’s facade and a smartphone-accessible tour of virtual murals throughout the city, the fall show took the idea of print- and pattern-making literally out into the community. In turn, an on-site printmaking workshop organized in conjunction with Imprint Projects and Malaspina Printmakers brought the larger public into the gallery.

Prince has since reached out to groups as diverse as the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, InTransit BC (he suggested installing Massey’s 2011 Via Lactea [above Glacier Lake] at the Yaletown-Roundhouse Station) and the PuSh festival (for which the CAG hosted the Lebanese multimedia performance artist Rabih Mroué and the London-based photographer and video artist Andrew Cross). “I want the CAG to be a transmitter,” says Prince. And he sees the gallery as attuned to both a cultural and a social role.

After Mroué’s performance The Pixelated Revolution (2011), about the Syrian protesters and the use of cell-phone images, earnest young students asked questions about activism, and members of Vancouver’s Lebanese community gathered for drinks and reminiscence. And a recent walking tour through Vancouver’s back alleys led by the artist Ron Tran included an installation in the nearby Wildlife Thrift Store on Granville Street.

According to Roy Arden, who worked with Prince and Ikon director Jonathan Watkins on two projects, “Nigel really believes in thekunsthalle as a place of enlightenment…as a place of progressive humanism.” At a time when those values are being lost, in an art world that often favours a more cavalier attitude or views art in terms of entertainment, commodity or didacticism, Arden praises Prince’s “stellar sense of outreach and involvement and education.

“I like Nigel’s prose. It’s clear and straightforward—Nigel doesn’t speak ‘artspeak’—that’s what I like. He’s articulate, but manages to keep it accessible. There’s sophistication to what he does, but it always offers an entry point for the uninitiated.”

Prince’s curatorial preference for solo shows (in three separate CAG spaces: the 700-square-foot Alvin Balkind Gallery, the larger, adjoining B. C. Binning Gallery and street-front vitrines) over group shows also indicates a certain respect for the artist, says Arden. “Group shows tend to use artwork to illustrate a theory, but Nigel puts the artists before the idea,” he says. “He lets each artist have the stage and do their own thing.”

And yet Prince links the work of the artists he exhibits in subtle, thoughtful ways that challenge and stimulate the viewer. The works of Fengyi, Stark and Massey, for example, offer different interpretations of worlds seen and unseen, tangible and intangible.

Arden says he was “excited” when Prince came to the CAG. “Ikon had one of the best kunsthalle programs in the world. I thought, ‘If he can bring any degree of Ikon magic here, then great.’” Noting that Vancouver artists like Ron Terada and Steven Shearer were also shown at Ikon, Arden is hopeful that at the CAG Prince will “continue to tap into his great international connections. It means we’re going to have a steady stream of good international work coming through here.”

When Prince first came to Vancouver in 2000, as part of a Canada Council–sponsored visit, he was impressed with the work he saw. “I remember heading straight to the Or Gallery and being wowed by Brian Jungen’s ‘Shapeshifter’ show,” he says. Having spent time in Glasgow in the 1990s, he observed a similar energy at work in Vancouver. It was an “artists’ town”—far from big commercial art centres, happily doing its own thing.

At a time when Glasgow-based figures like Douglas Gordon were enjoying international renown, Prince wondered why a generation of post–Jeff Wall artists were not as celebrated. It was a situation he tried to correct by giving several Vancouver artists their first European museum shows.

“Maybe it was because not enough curators and directors were travelling to Canada, because it was overshadowed by other countries,” he muses. “Maybe because the commercial sector across Canada was not getting out there in other parts of the world in the way that its European or American counterparts were at big international art fairs. But I could see right away that it was not necessarily to do with the quality of the work.”

His interest in Vancouver artists was sparked by a certain resonance with his own practice.

“I felt a kinship here with my own interest in artists who can connect us to the ‘everyday’ that is familiar to all of us. So Roy Arden, when he was making photographs, showed how economic shifts make tangible physical changes in the city. While the images he made were picturing Vancouver, they were familiar to a lot of postindustrial towns in the UK.

“When I first encountered Steven Shearer,” he continues, “with his paintings and drawings of heavy-metal fans—I remember being struck by how his work embodied a series of ideas and a cultural background that was familiar to me. I grew up listening to rock music in the suburbs.”

Prince’s interest in Vancouver continued for a decade. Then, Terada came to Ikon for a spring 2010 show and casually mentioned that CAG director Christina Ritchie was stepping down and board member Stephen Waddell was heading up the recruitment process. “Ron and I joked about my knowing Stephen from his time in Berlin, my awareness of the CAG, and my previous background in working with artists from Canada—and especially from Vancouver,” says Prince. Waddell followed up within a day or two.

“I thought he was an ideal candidate,” Waddell says. “His interest in the local art scene was wide-ranging, and not partisan in the way it often can be here. His curatorial vision was exciting. Oftentimes in Vancouver, the curators are ten years behind the artists. Nigel was someone I thought was right on track with where art makers were heading.”

Prince downplays the curatorial differences between Canada and the UK, but he does acknowledge different realities. “Some institutions focus on local artists wherever they may be in the world; others focus on a more international scope of programming. In part, pragmatics govern this: available funds, knowledge, et cetera. In Canada, perhaps it is magnified by geography—physical time and distance can hinder ambition and scope. In Europe, the relative concentration of differing art centres enables a greater ease of visiting, looking, conversing. And, of course, intensity can dissipate over miles. In part, it comes down to the ambition of the organization, too…a quality not necessarily limited to Canada.”

He also observes, “Within some circles, there’s a certain kind of cult of the individual, an art-world thing of curators’ names being credited, sometimes above those of the artists. I see all projects presented here as authored by the CAG—one way in which I attempt to build a sense of team.”

Indeed, Thursday-afternoon staff meetings with Nigel and his team—which includes the curator Jenifer Papararo, who has been at the CAG since 2004—are low-key yet well-organized affairs where everyone has a chance to air concerns and share information. Prince exudes an understated sense of leadership, but quickly refocuses things if they stray too far from the agenda.

“He’s rigorous without being uptight,” observes a local artist, while Massey notes, “He raises the bar aesthetically. He does an amazing job of bringing together disparate artists and practices and teasing out a common thread.”

An hour before the opening, Prince, in a charcoal Martin Margiela suit, stands outside the gallery with Heidi Reitmaier (formerly of the Vancouver Art Gallery and Tate Modern), whom he recently brought on board as a new educational consultant. Prince is critiquing the balance of light on the vitrine installations, noting that the phosphorescence and fluorescence might need a different mix.

Soon, he’s leading a tour for volunteers, then chatting up patrons and artists. “Welcome back,” he says to the artist Adad Hannah, who has just returned to Vancouver from Europe.

It’s interesting to note that in various art-school bands, Prince played bass guitar: he kept the rhythm going, which is what he does at the CAG. His arrival enjoys a serendipitous confluence with Vancouver’s contemporary art–world groove, and the CAG’s location—at the intersection of the old Penthouse nightclub, a condo development and a hipster cafe—speaks to the city’s new cultural possibilities.

“When I accepted the position,” he explains, “one of the things you have in mind is the geography—Vancouver is far from other parts of the world, especially coming from Europe where a lot of my networks reside. But what’s interesting is that in the year I’ve been here, there are some people from European galleries who I’ve actually seen more than when I’m in Europe. They represent artists here. I spoke to friends who are artists and other gallery curators and directors when I was in the process of moving here. There was a feeling that Vancouver is really on the art-world map.”

In the gallery, as a shoulder-to-shoulder crowd gathers to take in a show that balances Asian tradition, American invention and the stars of a big Canadian sky, there is a sense that Prince understands exactly where Vancouver is on that map.