This past summer, in a stand-alone cube not much bigger than a closet, Montreal-and-LA-based artist Nicolas Grenier reversed the give-and-take polarities of art-world commerce.

For The Time of the Work, Grenier invited 14 artists and one collective to contribute works to the Leonard and Bina Ellen Art Gallery’s “SIGHTINGS” project series. A select group of artists, critics and collectors then chose a piece. No money changed hands. Instead, each “acquirer” spent time—with only paper, pen and the artwork itself—inside Grenier’s customized cube, the length of their isolation determined by how long it took the artist to create the work in the first place.

A Pierre Dorion print equalled 3 hours, 14 minutes and 18 seconds; an Annie Hémond Hotte painting meant 13 hours, 47 minutes. Once the time was up, the work was theirs. In exchange, artists received the written reflections on time passing inside the cube. Value became a temporal transaction, and the acquirer became the acquired.

This coming to terms with the realities of cultural labour amid the dominant structures of social, political and economic value has been a constant in Grenier’s practice since his time as a grad student at CalArts in the late 2000s. As the only dedicated painter in his class at the epicentre of West Coast Conceptualism, the experience was a sharp check not only on the ideological contexts of his work, but also its formal roots.

“For the first crit, I made a huge painting that had very specific historical references,” he recalls of CalArts. “Nobody talked about painting in two hours. I was like, holy shit, everything I’ve learned has no value here.”

An even more fundamental shift came from what he found away from school: the light, the space and, most importantly, the city itself.

“Los Angeles is really fucked up,” Grenier says. “It encompasses the most extreme opposites, which I had never seen in Montreal.”

After graduating, Grenier rented a studio in LA’s skid row district, where the rampant disparities of wealth and class, and the xenophobic tensions of immigration and race, collide in an urban environment that, in Grenier’s view, reads like the built equivalent of social and economic discord.

“I realized that a lot of the built environment essentially embodies ideology,” he says, “where all of these things I found totally fucked up about the city are visually expressed.”

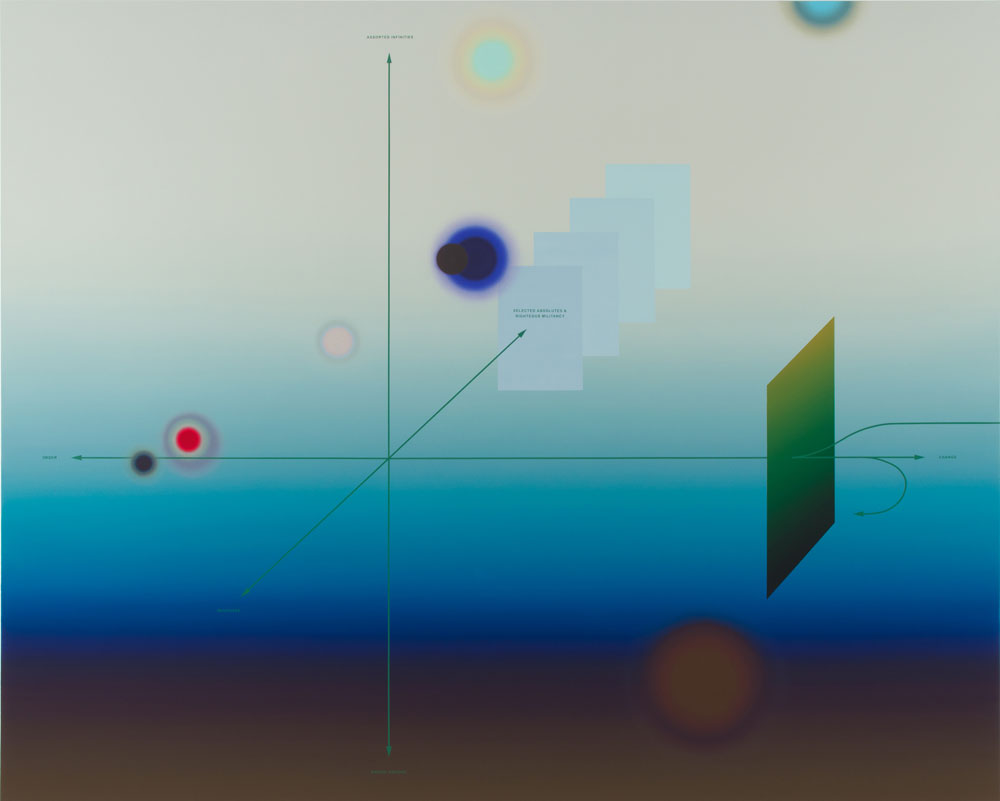

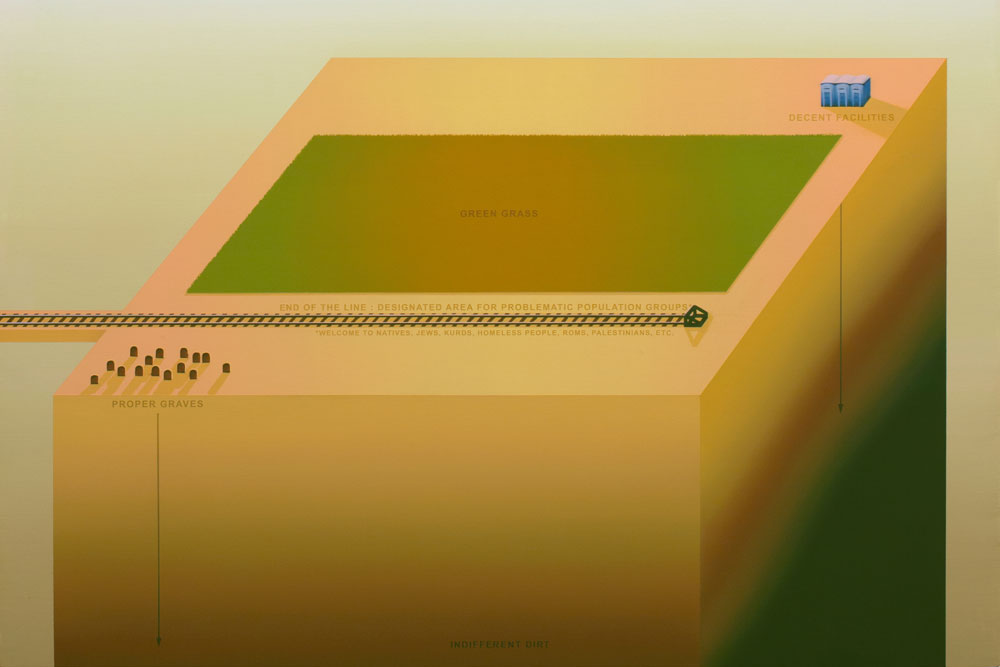

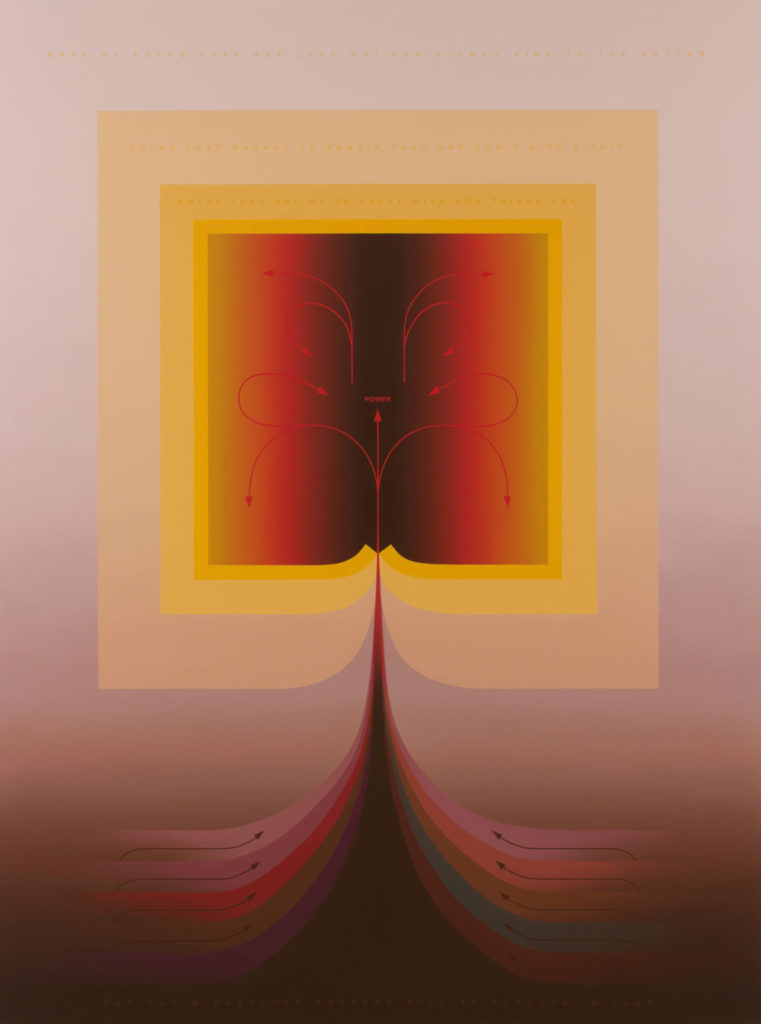

Grenier’s paintings—sometimes placed as “inserts” in architectural installations—reflect that structural unrest. Having been part of exhibitions this fall at Gagosian Gallery in Athens and Untitled Art Fair in Miami, the reach of these paintings is growing. They vibrate with the saturated hues of desert light and the conceptual mappings of institutional critique, yet remain anchored in the always-conflicted truths of everyday life. They are cautionary signposts, of a sort, to a destination as yet unknown.

This spotlight article, adapted from the Fall 2016 issue of Canadian Art, has been generously supported by the RBC Emerging Artists Project.

Nicolas Grenier, Selected Absolutes, 2016. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 2.17 x 2.67 m. Courtesy Galerie Antoine Ertaskiran. Private Collection.

Nicolas Grenier, Selected Absolutes, 2016. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 2.17 x 2.67 m. Courtesy Galerie Antoine Ertaskiran. Private Collection.

Nicolas Grenier, Promised Land Template (II), 2014. Detail. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 1.82 x 1.21 m. Courtesy Luis de Jesus Los Angeles/Galerie Antoine Ertaskiran.

Nicolas Grenier, Promised Land Template (II), 2014. Detail. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 1.82 x 1.21 m. Courtesy Luis de Jesus Los Angeles/Galerie Antoine Ertaskiran.

Nicolas Grenier, Promised Land Template, 2014. Installation view at Biennale de Montréal 2014.

Nicolas Grenier, Promised Land Template, 2014. Installation view at Biennale de Montréal 2014.

Nicolas Grenier, Promised Land Template, 2014. Installation view at Biennale de Montréal 2014.

Nicolas Grenier, Promised Land Template, 2014. Installation view at Biennale de Montréal 2014.

Nicolas Grenier, One Day Mismatched Anthems Will Be Shouted In Tune (II), 2014. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 2.03 x 1.52 m. Courtesy Luis de Jesus Los Angeles/Galerie Antoine Ertaskiran. The Progressive Art Collection.

Nicolas Grenier, One Day Mismatched Anthems Will Be Shouted In Tune (II), 2014. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 2.03 x 1.52 m. Courtesy Luis de Jesus Los Angeles/Galerie Antoine Ertaskiran. The Progressive Art Collection.