Last summer, during a presentation of Andrew Tay’s WorkingOn WorkingOnUs at the Toronto performance series PS: We Are All Here…, a dancer stepped on a light bulb. Performers moved exuberantly about the space, whipping metallic streamers through the air. Ecstatic bodies collided, and the impact sent a foot to find balance where a fluorescent bulb lay illuminating the wall from below. Hearing glass shatter, the dancers proceeded with unhindered enthusiasm to grab brooms and sweep away the danger before carrying on. The precarity of independent contemporary dance in Canada had rarely felt so viscerally, if inadvertently, represented.

To speak in any broad terms about Canadian contemporary dance is necessarily to misrepresent it. At the risk of rehearsing some over-determined metaphors concerning our nation’s size and scope: the work of experimental Canadian choreographers is as wide-ranging as the creative communities and ecologies from which these artists emerge. What’s more, many choreographers, here and abroad, are expanding how we understand the parameters of contemporary dance.

Too frequently, the contemporary is defined via specific Euro-American artistic genealogies. The work of New York–based choreographer Trajal Harrell has questioned this tendency—revising the dominance of postmodern dance, specifically the scene revolving around New York’s Judson Memorial Church in the 1960s, by placing its canonical practices in conversation with the movements and performative logic of voguing.

In a similar vein, Toronto-based Nova Bhattacharya, whose piece Infinite Storms was presented in January 2017 as part of the Theatre Centre’s Dance Card series, creates contemporary choreography with the precise techniques and gestures of Bharatanatyam, one of India’s classical dance styles. The work of Whitehorse-based Aimée Dawn Robinson demonstrates yet another approach, informed in part by the artist’s intensive academic research and training in Butoh, a form that emerged in Japan at the end of the 1950s.

Precarity exists across a spectrum of contemporary dance in Canada, and across the field’s history, too. In an attempt to bring dance’s past to bear on its present, choreographer and Dancemakers curator Amelia Ehrhardt‘s No Context, which premiered in March 2015 and was remounted for Edmonton’s Mile Zero Dance in March 2017, began as a commission from the Nomadic Curatorial Collective to create a dance based on archival documents from Dance Collection Danse (a significant and undervalued resource for dance history in Canada). The choreography features a text made by Ehrhardt, which is read by her best friend, Catherine Ribeiro, while Ehrhardt dances, exploring continuous gesture and flexible, porous interactions with the performance space.

Ehrhardt’s archival materials documented 15 Dance Lab, a small studio space and arts organization founded by Canadian dance artists and advocates Miriam and Lawrence Adams, also the founders of Dance Collection Danse. Ehrhardt focused on their failed attempt to create a dance centre at the site of a decommissioned TTC building in Toronto in 1976.

As her work recounts, the Adamses had envisioned this space, Studio Place, as a hub open to the Toronto dance community’s research, production and presentation needs. No Context not only asks what it means for dance in Toronto that this infrastructure was never realized, but also explores why we want such a space, what centralization and decentralization mean to a moving medium, and how social and political dynamics of power echo through all these questions.

As Ribeiro remarks at the beginning of No Context, Ehrhardt’s piece is Toronto-specific. And since its 2015 premiere took place directly across the street from the original 15 Dance Lab, we might wonder what the choreography means to spectators several provinces away. The issues it addresses, however, are certainly not singular: considering the work’s Edmonton remount, Mile Zero Dance artistic director Gerry Morita remarked to the Edmonton Journal that a lack of dedicated dance space is “something we’ve been complaining about here for a long time, so we will see if that resonates.”

The unrealized dream of Studio Place is, in some sense, coming true in Montreal. The Édifice Wilder Espace Danse assembles four dance organizations—Tangente, Agora de la danse, Les Grands Ballets Canadiens de Montréal and the École de danse contemporaine de Montréal—in what promises to be Quebec’s largest dance centre. It includes a wide range of well-equipped studio, laboratory and performance spaces and provides much needed stability to the organizations it houses and the dance artists they serve. Yet potential issues of accessibility, and questions of sustainability for such expensive infrastructure, linger, as they do in Ehrhardt’s contemplations.

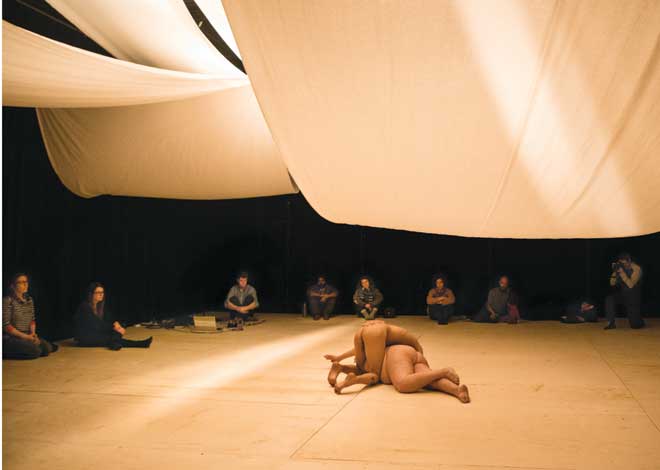

Discussing the Édifice Wilder project, Tangente’s co-founder and curator, Dena Davida, has frequently described her particular excitement to have spaces designed for greater flexibility—where, for instance, audiences can just as easily be facing the performance area as scattered around or within it. It’s a reflection that speaks to the essential role of the spectator in current choreography, as well as the need to find new ways of engaging audiences in experimental contemporary dance, which is widely critiqued as inaccessible or unapproachable.

Toronto-based Amanda Acorn’s piece multiform(s) premiered at SummerWorks in 2015, showed at Montreal’s Festival TransAmériques last June and was remounted at Workers Arts Heritage Centre in Hamilton in November. Its viewing experience is at once entirely open and inflected with moments of suggestion and guidance. Over the course of about an hour, the performers, surrounded by the audience on all sides, move through space in repetitive, gestural sequences without a discernible beginning or end.

Throughout, the dancers invite us to look purposely and imaginatively, their eyes suggesting possible pathways, trajectories and patterns for ours to follow. An arm swings, marking diagonal space from behind the back to the front of the torso. The arm accelerates forward and across, and our eyes follow, floating to where the fingers glance the air at the height of their momentum, then following the arm back downward. Motion, extension, release: the eyes move with the body.

In Winnipeg-based Ming Hon’s Chase Scenes #1–58 (2015), visceral, chaotic movement happens within a prop-filled space, accompanied by live-streamed projections made by the performers using portable cameras. During the piece, audience members have, according to writer Seema Goel, the “option of either viewing the live performance directly in front of them, or of turning their head away from the performers in order to watch the projected live footage.” Because the performance invites an oscillating gaze, it may remind us of everyday ways of looking, making us, in Goel’s words, “conscious of our vacillation between screen and person.”

Other choreographers are pushing beyond the visual entirely. What we are saying, produced by Toronto company Public Recordings in 2013, is comprised of the bodies of performers as well as chairs, microphones and portable amplifiers. Sound, reverberation, voice and conversation: all are at work to create the space and, in choreographer Ame Henderson’s words, to “expand our perceptive capacity.”

Benjamin Kamino, who works between Montreal and Toronto while studying in Amsterdam, creates a multi-sensory choreographic field in his 2014–15 piece m/Other+dark meaningless touch, which integrates the sounds of electronic music and performers’ soft speech, as well as a vibrating plywood platform, and aromas from scented oils worn on the dancers’ skin. The distance between performer and spectator typical of more traditional concert dance is elided as choreography takes root in the intimacies and proximities of sensing bodies.

Memory, geography and land also become essential choreographic materials in many contemporary practices. Montreal-based choreographer Lara Kramer’s forthcoming projects emerge from research in Sioux Lookout and Lac Seul, Ontario. Created in collaboration with photographer Stefan Petersen, Phantom stills & vibrations will take the form of an installation, composed from images and sounds that the two artists collected in these regions.

Kramer will also collaborate on a new performance alongside Petersen, sound artist Jassem Hindi and performer Peter James, exploring, as Kramer writes in an email, “the undercurrents of violence and the continued effects of genocide” in northern communities.

In 2015’s Body of Water Project, Aimée Dawn Robinson collaborated with Calgary-based Wojciech Mochniej and Saint John’s–based Anne Troake in a choreographic process that travelled between their respective homes. And in every location, the land asserted its collaborative potential.

As Robinson recounts in a process note from Long Lake, Whitehorse, “Anne and I waded it into the water, pushed the table legs into the silt, yelling and laughing from the impact of the cold water. With the immersed table, we created the brief illusion of standing (dancing, sitting, crawling) almost on the surface of the water. For the Body of Water performance in Whitehorse on Friday September 4th, 2015, we immersed three tables this way, end to end with enough space to wade between them. The cold water gushed off our heavy black clothing when we stood up. The shoes may still be wet.”

In Ehrhardt’s solo dances to nobody documented in still images only, an intimate interaction between body and immediate environment is accessible only through a series of still images on the artist’s website. At a June 2016 residency on Toronto Island called 8 Days, Ehrhardt mentioned to me that she has never lived more than five kilometres from Lake Ontario. Little more than a beach anecdote at the time, this observation continues to remind me that the geographies that surround us propose attachments and affinities as we move around them. Or, to quote Ehrhardt: “choreography: live your entire life five kilometres from one of the largest bodies of water in the world.” An alternate title for Ehrhardt’s No Context is We Actually Maybe Right Now Have Everything We Need.

Indeed, if there is a strategic game plan, a philosophical thesis or even an overarching aesthetic to experimental contemporary dance in Canada, this might be it. Ehrhardt and I recently discussed choreographer Dana Michel’s process in creating her piece LIFT THAT UP, presented by Dancemakers as part of Progress Festival in February 2016. “Dana just sort of showed up in our room to make the work,” Ehrhardt recalls, “and worked with the dancers who were here, the objects in the room, the room exactly as it was—and this is an aesthetic I’m seeing a lot of lately.”

Alexa Mardon, a Vancouver-based dance artist and one half of the duo behind online platform Dance Hole, paraphrases fellow Vancouver choreographer Justine A. Chambers: “dance…suffers from an economically survivalist mindset…. What could it be like to acknowledge the abundance of resources we might be able to call on in our communities, in our own bodies, in our friendships?”

This isn’t to suggest that dance artists shouldn’t seek more—support, space, engagement. Statistics continue to show that dancers remain the worst paid arts professionals in Canada; the challenges of sustainably making work within limited means remain taxing for many choreographers.

What Mardon proposes is an affirmation of the imaginative energies and collective care that nourish contemporary dance communities in the face of structural challenges. Sitting, crouching, kneeling and moving in the many spaces where dance happens in Canada, alongside the flocks of people who make it happen: sometimes it’s hard to imagine needing anything else.

Fabien Maltais-Bayda holds an MA in performance studies from the University of Toronto. He writes for publications including Esse, Momus and the Dance Current and is a writer-in-residence at Dancemakers.

This is an article from the Spring 2017 issue of Canadian Art. To get each issue delivered to you before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.