Mitch Mitchell is an artist, but also an alchemist. At heart, he is a maker of objects, imbued with quiet, yet epic histories. His recent solo exhibition at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, curated by Sarah Fillmore, was visually engrossing: inky black, fiery amber and charcoal-tinged. It felt both monumental and intimate.

Trained as a printmaker, Mitchell’s rigorous and industrious practice pushes the limits of traditional methods such as lithography, intaglio and silkscreen. He exploits the multiple—printed matter morphs into sculpture, film or performance.

Mitchell believes that inherent in printmaking is a “psychosis of the multiple.” He contends that physical labour can be at once a curse and a comfort. It is a torment but also a reprieve from past trauma—or in Mitchell’s case, perhaps, a way of coping with a tragic family history.

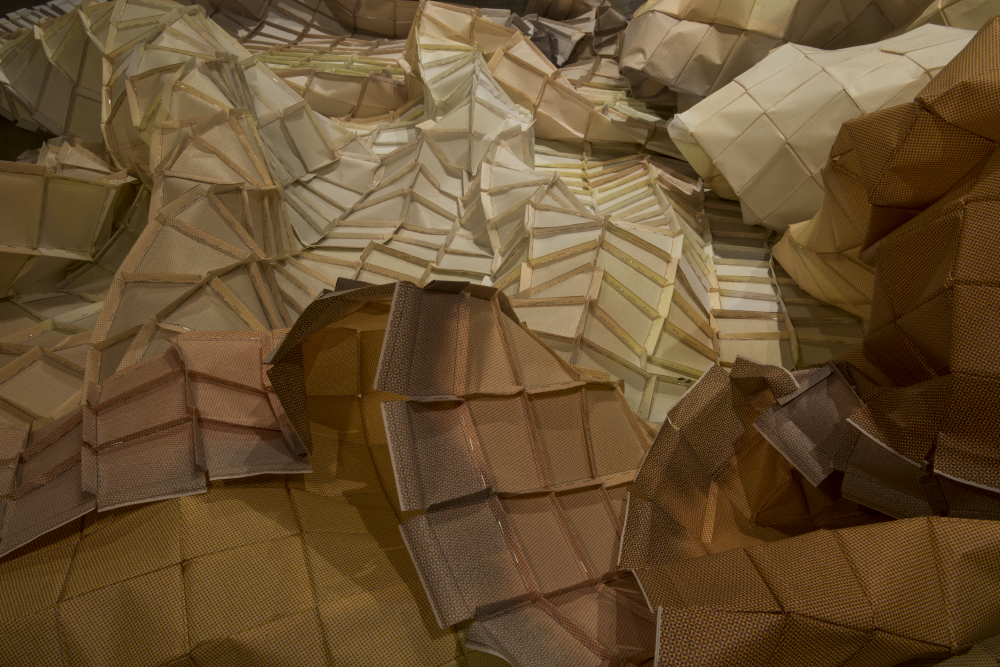

Another view of Mitch Mitchell’s Berth (2015–16), consisting of 35,000 handmade boxes created out of ink, paper, glue, and wood. Dimensions variable. Photo: Steve Farmer. Courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

Another view of Mitch Mitchell’s Berth (2015–16), consisting of 35,000 handmade boxes created out of ink, paper, glue, and wood. Dimensions variable. Photo: Steve Farmer. Courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

In BERTH (2013–16), Mitchell painstakingly constructed 35,000 boxes out of recycled paper and ink. In the guise of a Modernist cube, a dizzying number of boxes form a monolith on a shipping palette, while thousands of other boxes appear as a pile of rubble nearby. The carefully crafted boxes resemble shipping containers, alluding to the globalized nature of trade and mass production. Beyond the simple recycled materials, Mitchell sees labour as a fundamental, democratic ingredient. Labour embodies the strength of the human spirit, yet it is inherently tragic and Sisyphean. It is a physical and emotional test of endurance.

Lineage and family history come to light in Mitchell’s more recent works. Prior to the US involvement in WWII, Mitchell’s grandfather had been a promising pitcher for the Chicago Cubs farm team, destined for major-league glory. This never materialized, however, as he was posted as a radar technician off the Aleutian Islands. One fateful day, he unknowingly witnessed the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima as a single, devastatingly minute blip on his radar screen. In an instant he bore witness to the event that ushered in the nuclear age and “death on the scale of Gods.” Mitchell’s grandfather was sworn to secrecy and lived in quiet shame for the rest of his life as a coal miner in Danville, Illinois. This secret was only revealed to the family when the artist was 15 and military records were unsealed.

Despite the enormity and burden of such a family legacy, these works do more than just grapple with, or set this secret free. Mitchell’s work makes few overt allusions to Hiroshima, but captures nevertheless the emotional fallout of postwar life. The exhibition catalogue that is forthcoming this summer will feature a new work made in collaboration with the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Mitchell has asked visitors to share anonymous cellphone images of the sky overhead the A-bomb drop site. While his works offer a glimpse into a very particular family history, they speak to many who have been touched by tragedy, trauma or loss.

Resembling, at a quick glance, charred lumps of coal, the wood blocks in Mitch Mitchell’s Prometheus (2015–16) could actually, if assembled, be used to print an image of Hiroshima after the bomb. Dimensions variable. Photo: Steve Farmer. Courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

Resembling, at a quick glance, charred lumps of coal, the wood blocks in Mitch Mitchell’s Prometheus (2015–16) could actually, if assembled, be used to print an image of Hiroshima after the bomb. Dimensions variable. Photo: Steve Farmer. Courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

In Prometheus (2015–16) Mitchell immaculately constructed faceted wood blocks, whose form references the block in Renaissance printmaker Albrecht Dürer’s Melencolia I as well as the absolute geometry of the Fibonacci sequence. Positioned in piles and in an heirloom copper vessel, the blocks begin to resemble charred lumps of coal.

Each block is etched with a halftone dot pattern, offering the potential of hundreds of woodcut prints. If a composite image were ever to be made of the prints, it would loosely illustrate a famous photo taken by an unnamed photographer of the after-effects of Hiroshima.

The title Prometheus alludes to the Titan in ancient Greek mythology who stole fire from the Gods to share it with human beings. Mitchell literalizes this fire by burning and cauterizing the blocks using the traditional Japanese preservation technique of Shou Sugi Ban.

In his work The Alchemist (2015), Mitchell isolates a single block under a bell jar. Posed on a copper plate, it subtly reflects the image of a soldier’s face that is intricately carved into the block’s surface.

“I was thinking in my mind, how does an individual take something like this [experience] home and then live with it,” says Mitchell. “How do you describe destruction, how do you dismantle that part, how do you physicalize it?”

The single wood block isolated under glass in Mitch Mitchell’s The Alchemist (2015) shows the face of a soldier; Mitchell’s grandfather was a Second World War veteran. 27.94 x 27.94 x 22.86 cm. Photo: Steve Farmer. Courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

The single wood block isolated under glass in Mitch Mitchell’s The Alchemist (2015) shows the face of a soldier; Mitchell’s grandfather was a Second World War veteran. 27.94 x 27.94 x 22.86 cm. Photo: Steve Farmer. Courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

For Mitchell’s grandfather and a generation of veterans, physical labour became a kind of panacea to relieve emotional trauma. The Scots and the Irish have an expression for this coping mechanism: “working the devil out.” For Mitchell’s grandfather, coal mining filled this void.

Victory (2016) is a cast replica of the last baseball that Mitchell’s grandfather threw for the Chicago Cubs, a notoriously underdog team. It is done in the lost-wax method with victory wax.

Shown alongside Victory is a Civil War cannonball Mitchell unearthed in his grandparents’ backyard as a child that he emblazoned with the moniker “Official National League.”

Baseball is deeply rooted in the American psyche as the national pastime. Mitchell hints at the ominous connection between professional team sports and waging war. Both are strategic, calculated and competitive. It is unsettling to realize that weapons like grenades were originally designed to mimic the size and familiarity of a baseball for young soldiers.

Mitch Mitchell’s Victory (2016) is a victory wax replica of a baseball. During and after the Second World War, military technologists strove to make grenades that would approximate the size of a baseball. Mitchell’s grandfather, prior to the war, pitched for a Chicago Cubs farm team. Photo: Steve Farmer. Courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

Mitch Mitchell’s Victory (2016) is a victory wax replica of a baseball. During and after the Second World War, military technologists strove to make grenades that would approximate the size of a baseball. Mitchell’s grandfather, prior to the war, pitched for a Chicago Cubs farm team. Photo: Steve Farmer. Courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

The title of the AGNS exhibition “I Will Meet You in the Sun” is a direct quotation from a letter written by the artist’s grandfather to his then fiancée during the Guam offensive in World War II. Just a teenager, but deeply aware of his mortality, he made this heart-wrenching declaration of love as bombs fell from the sky.

History of a First Failed Industry (2014 to present) is a poetic tribute to Mitchell’s grandmother, too. A sculptural installation of a quilt made from printed matter, it is composed of silkscreened squares held together by more than half a million staples punched by hand. This laborious gesture (which caused the artist to break a bone in the process) demonstrates the real physicality of sewing.

Mitchell envisioned the quilt to be a kind of metaphorical hot-air balloon made from paper for Icarus, who flew too close to the sun. The image on the quilt is printed with rust-pigmented inks and is a halftone dot pattern of the sky above his grandparents’ home the night it sold.

From a distance, the billowing quilt appears to be printed in swatches of mustard and sepia tones, but up close, the thousands of halftone dots come into focus. They appear almost as a coded matrix of dots-per-inch, or can be likened to radar blips.

Mitch Mitchell created inks from several varieties and hues of rust to silkscreen the paper used in History of a First Failed Industry (2014–present). The work consists of hundreds of hand-stapled pieces of paper, with Mitchell actually breaking a bone during the process of repetitive labour on the piece. Dimensions variable. Photo: Steve Farmer. Courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

Mitch Mitchell created inks from several varieties and hues of rust to silkscreen the paper used in History of a First Failed Industry (2014–present). The work consists of hundreds of hand-stapled pieces of paper, with Mitchell actually breaking a bone during the process of repetitive labour on the piece. Dimensions variable. Photo: Steve Farmer. Courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

In his practice, Mitchell has developed a repertoire of materials he draws from, almost like a lexicon or vernacular, including paper, ink, wood, copper and wax. His choice of materials is deliberate and symbolic. They are “elemental” base materials with transformative properties as each has a melting point or stage of decomposition.

The inherent flaw of a substance becomes a gesture too; the matches in Remains (2016), for example, are made from copper, whose heat-conductive properties would make lighting them futile, not to mention incendiary.

In these works, the lifespan of a substance can be a metaphor for the physical and emotional limits of manual labour. Rust, used so explicitly in History of a First Failed Industry, comes to represent this point of erosion and decay. It is the after-effect of labour and industry, tracing the imprint we inevitably leave on the world.

Overall, the volatile, perishable nature of materials hints to mortality, a key theme in Mitchell’s work: “I’m using all these very democratic materials—and labour becomes a democratic material itself. And so time, performance, production, procedure, as well as death and melancholy—it becomes a very loaded thing. I take it on as very much a beautiful but tragic element in the work that takes centre stage sometimes.”

Mitch Mitchell, Remains, 2016. Copper, soot, graphite, shellac, 2.54 x 2.54 x 1.27 cm. Photo: Steve Farmer. Courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

Mitch Mitchell, Remains, 2016. Copper, soot, graphite, shellac, 2.54 x 2.54 x 1.27 cm. Photo: Steve Farmer. Courtesy of the artist and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

Mitchell’s works are truly hand-made, and although typically large in scale, their component parts are palm-sized. As artist Graeme Patterson has commented, this provides a universal frame of reference or human scale.

In essence, Mitchell uses traditional printmaking techniques in uncanny and uncharacteristic ways, creating familiar objects with hidden legacies. They are reliquaries of our history, present moment and impending future.

Leah Resnick is a curator, arts administrator and arts educator who is currently senior exhibitions manager at the National Gallery of Canada. Mitch Mitchell has another solo show upcoming from November 4 to December 24, 2016, at Galerie Nicolas Robert in Montreal, as well as one in the fall of 2017 at dc3 Art Projects in Edmonton.

This article was corrected on June 7, 2016. The original copy suggested that a cannonball Mitchell used in his work was unearthed in his backyard. In fact, it was unearthed in his grandparents’ backyard.