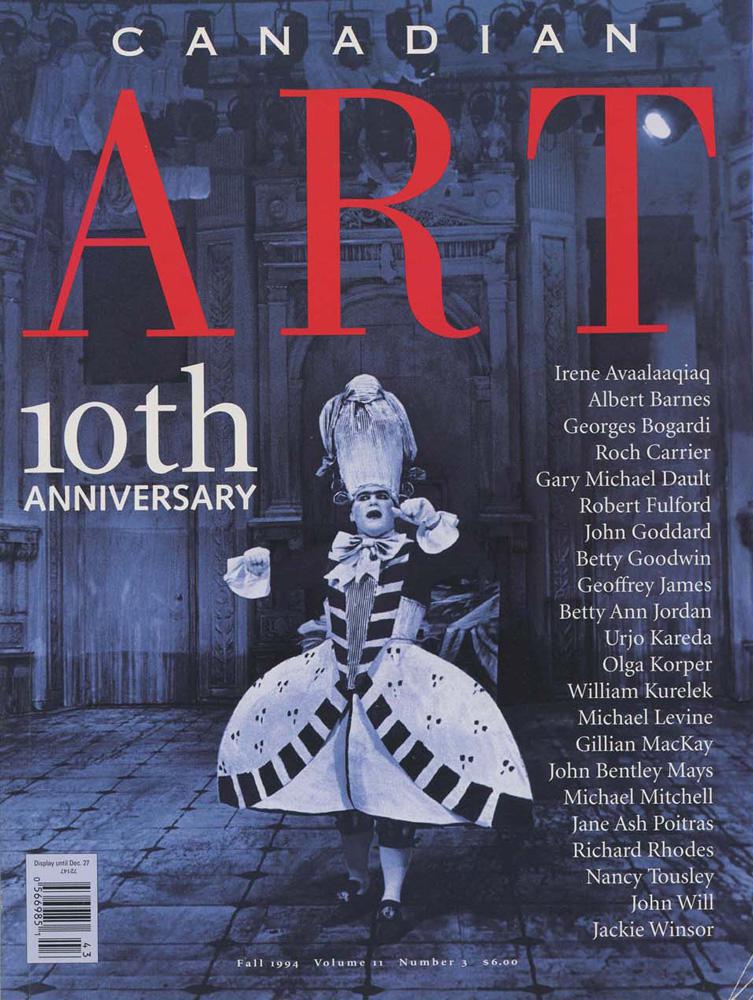

Of all estimable Canadian artists, Michael Levine probably works on the largest canvas. His creations often occupy spaces half-a-city-block wide and just as high and are seen by a couple of thousand people at a single viewing. As an extraordinarily imaginative stage designer, Levine has created pictures in the theatre that resonate tellingly with the action onstage and then invade the audiences’ memories, inescapably, for years afterward. Mention some of his productions, and you may struggle to recall who was in the cast, or you may dredge up a dim outline of some of the staging, but you will find that the images created by Michael Levine are still with you: the huge red Expressionist woodland of Frank Wedekind’s Spring Awakening at the Bluma Appel Theatre; the dreamworld library, its walls climbing upward before our eyes, of Heartbreak House at the Shaw Festival; the yearning household of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya with its cramped and claustrophobic rooms enclosed by sky-blue walls painted with golden stars, at Tarragon Theatre; the tier upon tier of women’s red evening gowns as the backdrop for Clare Boothe’s The Women at the Royal Alexandra; the weeping watery floors and the ominously angled brick wall of the Canadian Opera Company’s double-bill of Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle and Schoenberg’s Erwartung at the O’Keefe Centre; and the dark Italian seaside resort, relived only by a thin strip of the Mediterranean and a burst of Fascist banners, in Harry Somers’ Mario and the Magician for the COC at the Elgin Theatre.

So begins our Fall 1994 cover story. To keep reading, view a PDF of the entire article.