Poetic abstractions for measuring mortality, difference and time

Micah Lexier has so far produced an almost poetic oeuvre of minimalist, conceptual artworks, many of which illustrate the degree to which artistic creation itself has lately become so abstract in its premises that artists do not have to fashion a thing for observation by the self so long as they perform a drama of measurement on the self. Artists no longer “give meanings” to a life so much as they “take readings” of a life—plotting dots on a graph, counting days on a chart, processing each bit of raw data according to a self-reflexive, self-analytical procedure, for which the expected lifespan of the artist might provide the unspoken, but official, standard of temporal measure.

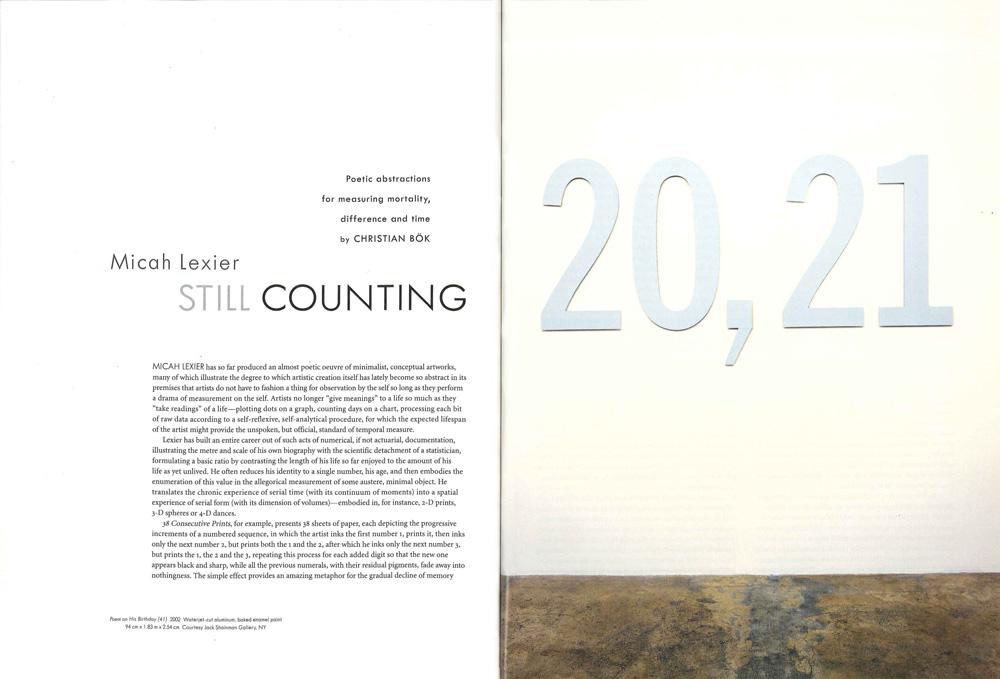

Lexier has built an entire career out of such acts of numerical, if not actuarial, documentation, illustrating the metre and scale of his own biography with the scientific detachment of a statistician, formulating a basic ratio by contrasting the length of his life so far enjoyed to the amount of his life as yet unlived. He often reduces his identity to a single number, his age, and then embodies the enumeration of this value in the allegorical measurement of some austere, minimal object. He translates the chronic experience of serial time (with its continuum of moments) into a spatial experience of serial form (with its dimension of volumes)—embodied in, for instance, 2-D prints, 3-D spheres or 4-D dances.

38 Consecutive Prints, for example, presents 38 sheets of paper, each depicting the progressive increments of a numbered sequence, in which the artist inks the first number 1, prints it, then inks only the next number 2, but prints both the 1 and the 2, after which he inks only the next number 3, but prints the 1, the 2 and the 3, repeating this process for each added digit so that the new one appears black and sharp, while all the previous numerals, with their residual pigments, fade away into nothingness. The simple effect provides an amazing metaphor for the gradual decline of memory through the passage of history when the imprint of such a past may be felt, but is no longer seen.

39 Wood Balls, likewise, dramatizes the historical perception of selfhood, insofar as the work consists of spherules arranged sequentially from the smallest diameter to the largest diameter (much like a line of successive planetoids), each size corresponding to one year so far lived in the life of the artist. While the maple balls might appear uniform in both shape and matter, the grain of the wood in each sphere demonstrates, of course, its own unique patterning, as if to suggest that, while the growth of the artist corresponds to a specific identity, each year varies from the next in both mood and tone, expanding like the concentric boundaries seen in the rings of a tree.

A Performance for One Dancer and 39 One-Pound Weights also provides an allegory for the aging of the artist. A dancer, initially burdened with a slight weight of one pound, must perform a leaping routine 39 times, each time adding an extra pound of weight, until the dance, which begins in a mood of effortless vitality, shifts toward a mood of cumbersome gravity as the dancer begins to adjust to the metaphorical encumbrance of all the added years. Lexier may even be suggesting that history itself has become a burden for the minimalist, conceptual artist, who must try to innovate upon the artistic regimens of the past.

Lexier offers two visions of history, in which the artistic memory of the past fades (like the words on a page) even as the artistic matter of the past grows (like the rings of a tree). He responds to the historical precedents set by conceptualists like Joseph Kosuth and On Kawara (among others) by placing his own work in sequence with theirs, repeating their serial method by following a set of fixed rules for producing a rigorous sequence of incremental variations upon the work of conceptualism itself. Any adjacent elements in such a series might differ only marginally, but over the course of this sequence the gradual changes lead to a difference in species, not in degree.

Kosuth in (Art as Idea as Idea) [meaning], for example, might print a text that defines the meaning of the word “meaning,” reducing the production of art to a definition of art itself, whereas Lexier in the series Two Actions (write a text and cross it out) might simulate, then renounce, such conceptual linguistic traditions by recording in stencilled aluminum the process of transcribing, then obliterating, verbatim, the written command “write a text and cross it out.” Such conceptual artwork often broaches the same concerns as procedural writing (calling to mind the rigorous formality of Oulipo, the famous French clique of avant-garde intellectuals, whose poetic output often exhausts the potential of some self-referential, self-explanatory constraint).

In True Three Ways (Word Count, Letter Count, Line Length) Lexier performs an almost Oulipian exercise by writing in pale, neon tubing: “the thing/half/two times the thing”. The poem is true if, for example, “the thing” considered is letter count, since the first line contains “the thing” (eight letters), while the second line contains “half” (four letters) and the last line contains “two times the thing” (16 letters). While he knows that such conceptual artwork often uses textuality to dematerialize the experience of artistic “thingness,” his own procedural writing uses textuality to rematerialize the experience of artistic “wordiness”—aestheticizing the internal, rational logic of language itself.

Lexier’s most recent show at Robert Birch Gallery, “One of These Things,” suggested a slight shift in interest from a more formal, but biographic, work to a more casual, but impersonal, work—focusing more directly upon the substance, if not the substrate, of the mark upon the page. In Letter-Size (Flat), for example, he displays eight sheets of aluminum, each measuring eight and a half by eleven inches and each cut, like a tangram, into a set of colourful, polygonal fragments. Each sheet suggests the crease pattern created when a piece of paper is folded, then opened, so that each page becomes a broken puzzle whose fitted shapes collide in a jarring, angular geometry of colours.

Works in the series One of These Things also consist of simple puzzles, for example one made out of a number of square commas, each comma blown up to a huge size in enamelled aluminum and then arranged adjacent to the others like the pieces of a mosaic. The title refers to the childhood diversion in which a toddler must learn to recognize, amid a set of diverse objects, the one anomaly that “doesn’t belong” because “it’s not like the others.” All the commas do appear virtually identical—except that each one breaks subtly in one way from all the rest (so that, of the four, one differs only in its surface coloration, while another differs only in its spatial orientation, and so on).

One of These Things / Braces, likewise, consists of a simple series made out of six script braces that are enlarged and then placed with the others like the tokens in a series. This work, moreover, constitutes a set in which each element shares all traits with the rest except for one (be it colour, height or some other subtle difference). The font characters almost resemble a collection of wingspreads or mustachios, each catalogued and identified according to some relative standard that might either include or exclude a specimen, depending upon the criteria used to classify such an element in a set.

Commas and braces often punctuate sets (commas might separate indexed members from each other, while braces might envelop them into a grouped listing). Both types of punctuation mark off any phrase that might otherwise be regarded as optionally extraneous. Such punctuation identifies a phrase as different, because, unlike the others, such a phrase can be removed from the series without altering the internal cohesion of the series itself. Just as the signalling of this difference in a text causes the reader to pause, so also must we stop to think for the briefest interval about which comma or brace does not belong within the offered artwork.

Lexier uses these lingual markers to suggest that if language constitutes a system of differences, a system that parses the world into gradations of value and categories of taste (discriminating among things in order to discriminate against one thing), then minimalists interested in linguistics must concern themselves with the value of the minimal anomaly— the smallest possible difference that can make a difference. The minimalist introduces the slightest obliquity into the repetition of a normal series so as to transform an ordinary sameness into a fabulous deviance. The subtle nuance of this dissimilarity suggests that, paradoxically, art itself can only belong to any set by trying, in the end, not to belong.

This is a review from the Spring 2005 issue of Canadian Art.

Spread form the Spring 2005 issue of Canadian Art

Spread form the Spring 2005 issue of Canadian Art