The way most people first see them, through the windows of cars rushing down the autoroute exit ramp and into Montreal by the Boulevard René-Levesque, the ten tall objects sparkling in the sunlight look vaguely like the work of David Smith, the greatest of American sculptors. They’re vertical and totemic, they’re metal and some of them have arm-like sections that shoot out, Smith-style in unexpected directions. But when examined closely, these aren’t at all like Smith’s sculptures, or like the many pieces of ironmongery by his imitators that now litter American cities. In fact, these are as far, aesthetically, from Smith’s work as it is possible to get and still remain within modern culture. Where Smith’s art is as instinctive as Jackson Pollock’s, the sculptures beside the autoroute are the product of elaborate research and intense thought. And where Smith’s subject-free sculptures deny any purpose except the romantic expression of form, these works not only refer to history but are frankly called Allegorical Columns and fulfill a specific function: they exist not only for their own sake, as handsome shapes, but also as silent commentators on the buildings around them. They are the focus of the garden of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, which—in the words of Phyllis Lambert, the major benefactor, founder and first director of the Centre—“metaphorically reinterprets the CCA as a place dedicated to architecture.” Heavy with symbols and signs, they are as self-conscious as any work of our time. They are also, taken together, the most ambitious public art produced in Canada in this generation.

And perhaps the most challenging as well. Melvin Charney, the 55-year-old architect and artist who designed both the garden and the sculptures, has been making challenging and difficult art for two decades, but usually within the comparative privacy of museums and galleries. With the opening of the CCA garden (and the almost simultaneous dedication of his smaller The Canadian Tribute to Human Rights monument at the corner of Elgin and Lisgar in Ottawa), Charney moved his unusual sensibility outdoors and gave it permanent and public form for the first time. The results are impressive, but they are not comfortable. Charney deals in social memories, metaphors of history and puzzles of culture. At any given moment we can find his art both broadly historical and intensely personal.

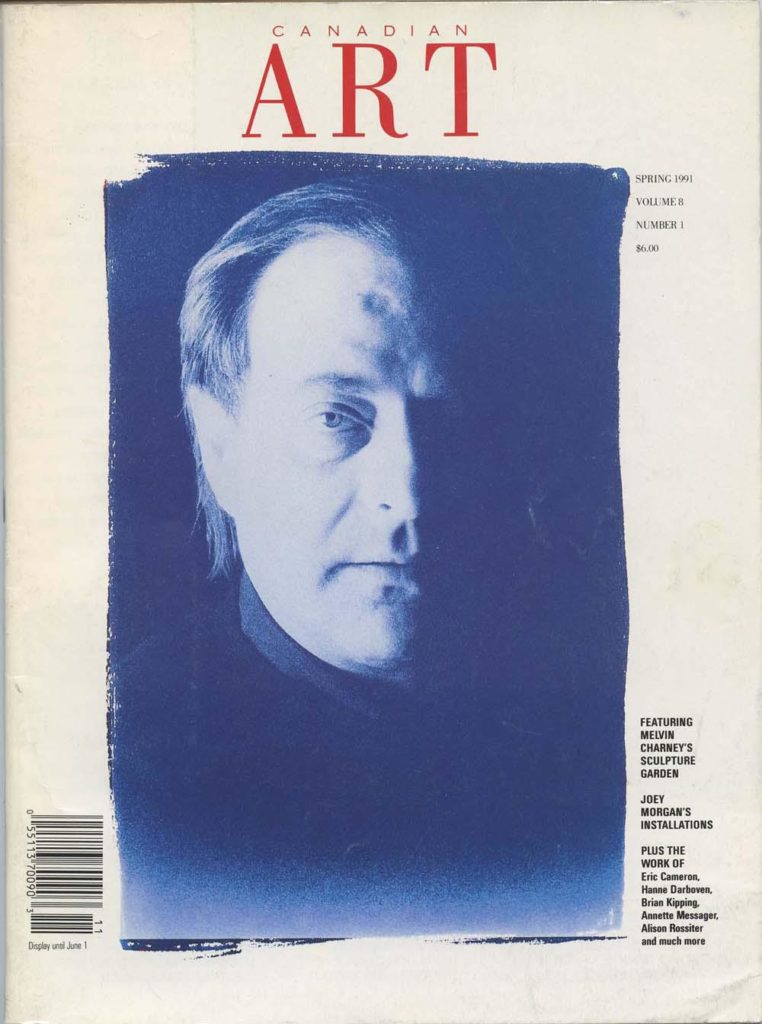

So begins our Spring 1991 cover story. To keep reading, view a PDF of the entire article.