Note from the editor: From time to time we dip into our magazine archives, which stretch back to 1984, to highlight profiles and features that might be of renewed interest to contemporary readers. Given the 50-year retrospective of Mary Pratt that is currently on view at the Rooms in St. John’s and is due to tour Canada in the coming years, it now seems an opportune time to revisit Robin Laurence’s insightful profile of Pratt from our Summer 1994 issue. Originally titled “The Radiant Way,” and offered as that issue’s cover story, Laurence’s article traces the development of Pratt’s career from childhood, and through many doubts and challenges, to popular and critical success.

An exaltation of the senses—that’s what Mary Pratt’s paintings sing out. And more. A complexity of themes and images—the creative and procreative, the environmental and the ecumenical, the sexual, the sacrificial and the subversive—is compressed into work that Pratt once described as merely “superficial.” In her statement for the 1975 exhibition catalogue Some Canadian Women Artists, Pratt wrote that she painted “objects that are symbolic of nothing except a very mundane life…I simply copy [their] superficial coating because I like the look of it.” From a nineteen-year distance, that disownment looks perverse. But it was also strategic. With parents, husband and children looking on, Pratt was not prepared to reveal the erotic impulse that is at the heart of her work. Nor would she discuss, at that still tentative time in her development, the way her work’s symbolic intent reveals itself as she paints. “I see something, I’ve got to have it, I’ve got to keep it, I’ve got to paint it,” Pratt says now. “And then, after I start to paint it, I realize why.”

Even as a young child, Pratt was captivated by the way “light graced an object” and felt an inchoate longing to preserve the fleeting appearance of things. Still-life moments occurred every day, in the way the cream streamed over homemade apple sauce, or the brown sugar glittered on her morning bowl of porridge. Although in her youth she was painting, drawing, taking art lessons and winning a prize in photography, “none of it,” she says, “made sense” to her. “When I went to an art gallery, I didn’t know what to look for. I didn’t know what made a painting great. I was dead to the world of art.” It wasn’t until she was well into her thirties that Pratt was able to connect the practice of painting with her own desire to own and preserve those rapturous moments of light-drenched looking. Art making was simply another lovely flower in the “civilized and friendly garden” in which she spent her childhood.

The conditions of that childhood are manifest in Pratt’s 1972 painting Fredericton. Morning sunlight, streaming across broad lawns, stately homes and towering elms, articulates the social and economic privilege, the blessedness, of her early circumstances. Yet something in the orderliness of the scene suggests the private discipline and public obligation that attended that privilege. Pratt’s maternal grandmother, Edna McMurray, dedicated her life to community service through the IODE, and her father, William J. West, a prominent lawyer, judge and Conservative politician, was also committed to an ideal of public life.

Although Mary Pratt is firmly identified with the well-managed domestic realm—with images of gleaming casserole dishes, sparkling jars of jelly, pristine tea sets, immaculately white laundry hanging on the line — her adult involvement with the natural project of housekeeping was neither easy nor natural. “I came to domesticity with great difficulty. I was not a tidy child. My mother did not instruct in the art of the domestic—she was a very half-hearted housekeeper.” Neither Katherine West, Pratt’s mother, nor Edna McMurray had any interest in polishing silver or dusting knickknacks, not only because these activities bored them but because of associations of vanity. “You weren’t supposed to aggrandize yourself,” Pratt says. “You were supposed to be of service to the people around you. That, basically, was the direction of my upbringing.”

This sense of service was deepened by the teachings of the United Church, in which Pratt was raised. She regularly attended church, taught Sunday school, participated in mission bands and church camps, yearned to be a missionary. Her parents read Bible stories to her and, as a small child, she was deeply moved by accounts of the infant Samuel praying for a revelation. The infant Mary would kneel on her bed and pray in Samuel’s words: “Speak, Lord, for thy servant hears.” Although she later drifted away from organized religious practice, her art is profoundly informed by Christian symbolism and a sense of the sacred in everyday life. Prosaic activities like preparing food and bathing babies take on sacramental significance: turkey drippings in a silver spoon become the holy oil of ordination; a disposable diaper transforms into an embroidered christening cloth. Pratt repeatedly returns to symbolically charged images like apples, pomegranates, bread and fish—especially fish. The family meal evokes communion, the Eucharistic sacrifice. Light streaming over bowls of fruit, cut flowers, roast turkeys, wedding dresses, is annunciatory, transfiguring. Light is the most essential element in Pratt’s work: the epiphanies it represents are particular to each scene, but are also crucial to her entire career. “I really believed,” Pratt says, “that God would speak to me.”

At eighteen, Pratt declared to her father that she couldn’t be an artist because it was “too selfish.” He responded, Pratt recalls, with the argument that it would be selfish of her not to be an artist. “‘You have a talent and it is a requirement of you to paint,’ he told me. ‘It is your fate—you’re going to have to study art.’” In 1953, Pratt enrolled in the Fine Arts program at Mount Allison University in Sackville; her teachers included Alex Colville, Lawren P. Harris and Ted Pulford. In 1956 she left with a certificate, returning in 1959 to finish her BFA. In between, she married Christopher Pratt, moved with him to Glasgow so that he could attend art school there, and gave birth to the first of their four children. The second was born in 1960, as Mary Pratt struggled to complete her degree. She worked at home while caring for her two babies, and spread her final year of courses over a two-year period. “There were days when I really thought I wasn’t going to make it…I didn’t do very good work, either. The professors understood that I was having a terrible time.”

Although the story is an old one, it’s still shocking when Pratt recounts what Harris advised her in her graduating year. “‘You know,’ he said, ‘that if two artists are married, only one is going to be successful. And in your family, it’s going to be Christopher. So why don’t you just understand that and look after the house and the kids.’” Pratt went home in tears from this interview, but she says she bore—and bears—Harris no ill will. “It was a wonderful thing for him to say to me because I realized absolutely my position at that point.” Harris’s words triggered Pratt’s fierce contrariness, forging her resolve to carry on painting. “I’ve always felt that of all the things I learned at art school, that moment was probably the most important.” Nonetheless, it would be years before she could place her own career needs before those of her husband’s, or consolidate a sustaining vision out of the demands of her growing family. (Two more children were born, in 1963 and 1964.)

The entwining of Mary Pratt’s life with that of one of Canada’s most acclaimed realist painters has been—and continues to be—immensely difficult and passionate. Not for Mary the decision to forego husband and children in the furtherance of her painting career, even after Christopher, in the furtherance of his painting career, moved the family to an isolated cottage on the Salmonier River in rural Newfoundland. “There was terrible resentment,” Mary Pratt says, concerning Christopher’s early successes and her own forfeiture amidst the diapers and the dishpans. She didn’t stop painting entirely, even though conditions in Salmonier were, when the family moved there, “medieval.” Grabbing whatever moments she could at her easel, Pratt produced work in a style which she now characterizes as “impressionistic.” But she felt herself to be drifting, without a defining theme or direction, until the now-famous moment in 1968 when, mopping the bedroom floor, she was suddenly arrested by the sight of sunlight pouring over the unmade bed. The experience was one of visceral recognition and creative epiphany: through it, she understood what the nature of her painting project had to be, capturing not only the way light transformed the domestic moment, but her own physical response to it. “As soon as I had that gut reaction, I knew that it had to be a sensuous thing, an erotic thing with me. It was no good to intellectualize.” She muses now about the connection between that adult moment of vision and her childhood prayers for revelation. “Maybe that longing to be shown the world helped me later when the world did show itself visually to me.” Other revelations followed, in the kitchen, in the garden, in odd corners of the house, scenes that triggered the same compulsion to preserve and possess the moment into which all that gorgeous, holy, fleeting sensation was compressed.

Pratt now had her subject, apprehended if not entirely understood, but hadn’t yet arrived at her method. Instead, she painted as quickly as possible on the spot, in an attempt to record the evanescent effects of light on colour, form and texture. She worked this way until she had another revelation, this one coming not from God or her own unconscious, but from Christopher. He persuaded Mary that photography was the only way she could make notes of the visual incidents that so compelled her. The first work in what would become her distinctive style, Supper Table (1969), was painted from a slide Christopher had insisted on taking.

“I think art stopped with the Renaissance,” Mary Pratt says, “and I don’t think it started again until the camera was invented.” The camera, she believes, “freed the artist”—it certainly was her own “instrument of liberation.” Keeping a loaded camera at hand, she seized images from her hectic daily round—fish fillets on wings of tinfoil, groceries standing in their crumpled brown bags, cakes cooling on sideboards, cracked eggshells in their sodden crates—then worked up her paintings from the slides. Mary Pratt was finding extraordinary meaning in the ordinary shapes and textures of domestic life, especially of food preparation. Painting from slides was also a means of claiming a kind of realism distinct from Christopher’s. The distinction, though, is ironic, since many of Mary’s early works were made from slides Christopher had taken. Still, their ultimate realization is Mary’s: where his style is flat and still, soberly engineered and geometrically generalized, hers is lively and exuberant, saturated with light and colour, scintillating with particularity.

Despite—or perhaps because of—its liberating aspect, the use of the camera as a painting tool was initially troubling for Mary Pratt. Her own doubts were amplified when her parents registered their disapproval. “They were very upset that I was working from photographs. They thought it was immoral, they thought it was cheating.” Painting in isolation, Pratt was unaware of the contemporary photo-realist movement occurring in the US, Europe and even London, Ontario. Nor could she muster precedents in art history to defend her own position. “I really didn’t know that Degas had based his work on photography, I didn’t know that Picasso had ever heard of a camera, I didn’t know anything.” For a despairing period in 1970, she gave up painting entirely. “I felt that I was debasing my own profession,” she says. But then her husband and children persuaded her to take up her paintbrushes again, to reconcile her puritanical scruples to the demon photograph. In fact, her sense of maternal responsibility overrode her daughterly dutifulness when her own young daughter, Barbie, asked her, “Mummy, if you’re not a painter, what can you be?”

Pratt is dedicated to an ideal of a family. “You fight to preserve it,” she says, “because that is the basis of our civilization.” Yet the sense prevails, looking at some of the images she has made famous—a bowl of Christmas pudding tightly covered with tinfoil and tied with string; six cooked apples in the close cell of a metal baking pan; slices of raw trout twisted in a Ziploc bag—of the beautiful and terrible constraints of family life. Nothing could be more seductive or more suffocating than the glistening, transparent plastic wrap Pratt has so frequently challenged herself to paint.

Analogies are often made between Pratt’s paintings and the still-life tradition of Northern Europe. But of course, when seventeenth-century Dutchmen were painting bread, fish, cheese and fowl, they weren’t in danger of being ensnared in gender stereotypes. Only in our age has the domestic become an issue in feminist discourse: on the one hand, it’s important to honour and validate the things women spend their time doing. On the other, well, there’s more to women than keeping house. Consciously or not, Mary Pratt has staged this conflict in a number of her paintings. She condemns the romanticizing of the still life by European painters, and strives for a quality in her own work which she describes as “vicious reality,” a quality that she sees as particularly North American.

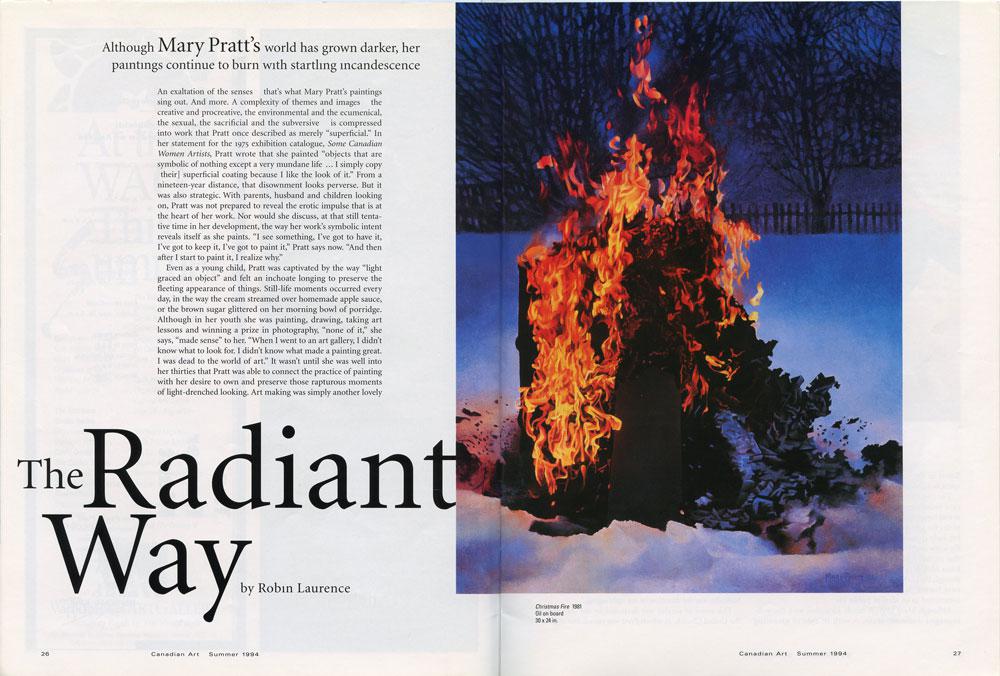

One aspect of this vicious reality is the recurring image of sacrifice: bleeding fish, burning paper, eviscerated chickens, broken eggshells, a moose skinned, quartered and hanging by ropes against an expanse of frozen white. An almost totemic sense of appeasement attends these images of trussed, gutted and sectioned flesh, as if Pratt were honouring the spirits of the creatures that have relinquished their lives to human consumption. But evocations are multiple, the Biblical made contemporary with concerns over political and environmental issues. The fish, for instance. In Pratt’s work, fish are archetypes of life and abundance, of fertility and resurrection. But they are also markers of economic and cultural identity, and gauges of environmental degradation. “Fish are the beginnings of life for us,” says Pratt—meaning all of us. “It’s terrible to think that they are in trouble.” Salmon between Two Sinks (1987), an image Pratt has painted in both oil and watercolour, is as gorgeous as all her fish paintings—bars of light flickering over adamantine scales, creamy skin, and glistening eyes — but the way the gutted fish is suspended, as if leaping, gasping for breath, between two realms, speaks of a desperate transcendence.

Over the past two decades, Pratt has achieved unassailable success and a large degree of freedom. Paradoxically, her work has become, she says, “more pessimistic.” In the face of significant life changes—crippling pain from arthritis, the departure from home of her children, a complicated dwelling-apart from her husband, hip surgery, moves from Salmonier to St. John’s to Toronto and back—her paintings have become more overtly symbolic, more considered and more sombre. It’s as if the light of her early epiphanies were being overwhelmed by the darkness of a larger social and historical condition. But it also seems as if she is consciously using her paintings as theatres of personal pain, places in which to confront crisis—and survive it. Amongst the earliest of such works is Service Station (1978), in which half a moose carcass is “crucified” on the crossbar of a tow truck. Repulsed, Pratt had taken a photo of the scene but had refused to paint it for years, thinking that it was “too much of an obvious thing.” Yet, after a desperate period of physical and emotional crisis, when her children had been ill and she herself had miscarried twin babies, the image became a relevant, even necessary allegory of the human body. Gruesomely sexual, the splayed and bound legs of the beast suggest a gamut of male violence against women.

In 1983, when Pratt was daily confronted with a childless house, she painted an image of her first grandchild having her first bath. The baptismal analogies in Child with Two Adults are obvious. Yet even with its evocations of strong new life, of spiritual purification, there is a sense here of jeopardy, as the bathing bowl—the baptismal font—hovers between darkness and light. The vivid, bloody red of both baby and bath water seems to connote infant sacrifice, and it can be no accident that this child is female. Wonder and dread attend her ritual rebirthing.

Another female rite of passage, the wedding, is explored by Pratt in her 1986 series of paintings, Aspects of a Ceremony. Pratt explains that she undertook this culturally charged subject at a time “when my own ideas about family life and marriage were changing.” Again, her theme seems to be one of sacrifice, most explicit in the apprehension of the bride in Barbie in the Dress She Made Herself and the virginal white gown, infused with rosy pink light and hanging in a tree, in Wedding Dress. Pratt is fascinated, she says, with the willing reenactment of this “primitive ritual” of submission by new generations of young women.

After nearly a decade of experimentation with other subjects and media, Pratt has recently returned to making small still lifes in oil. “There are some huge landscapes I want to do, and a lot of work with water and fire. But where I seem to be most at home and most particular is in this area of still lifes.” The domestic existence she now depicts is both more lonely and more contemplative, and the paintings reflect that. “Living alone has made the work stronger,” says Pratt, but then admits that this new condition conflicts with her early training—and longing—to serve others. “It never leaves me,” she says. “So I’ve had to come to the conclusion that my paintings are going to do that job for me.”

This is an article from the Summer 1994 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from our archives, check out Ken Lum’s article on Canadian cultural policy from our Fall 1999 issue.