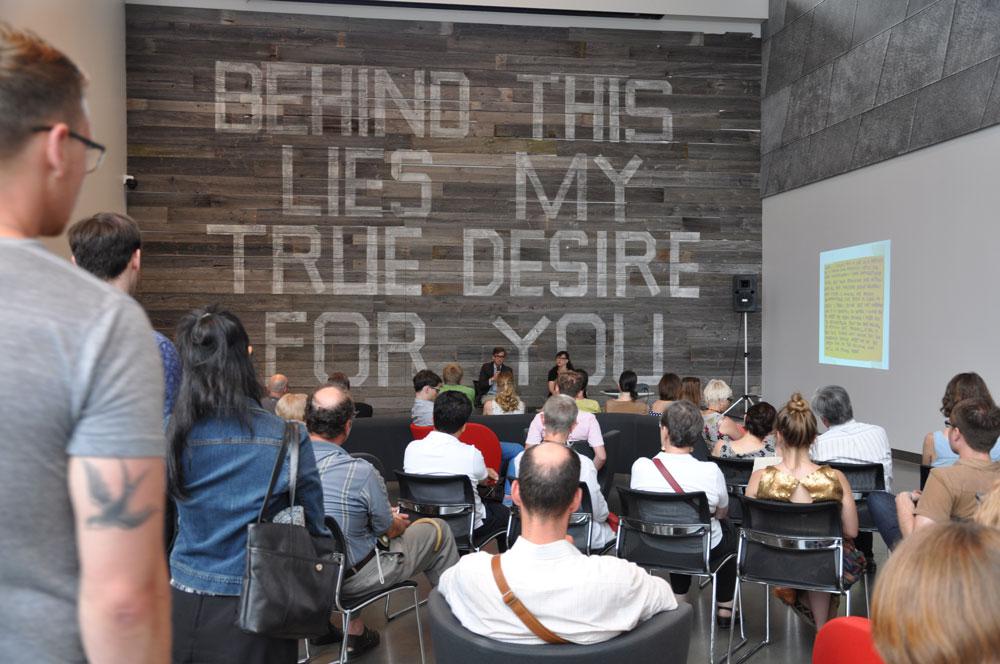

Museum renovations and rebrandings have become de rigeur over the past decade in Canada. But in his latest work, Behind this lies my true desire for you, Montreal artist/critic Mark Clintberg is using the Art Gallery of Alberta‘s recent refresh as creative fodder. In this interview, he tells Leah Sandals why.

Leah Sandals: The promotional text for this project, which is installed in the AGA’s Manning Hall, suggests that it’s a response to the gallery’s recent renovation and rebranding. How so?

Mark Clintberg: The new campaign for the AGA is “Your AGA,” which I thought was a really interesting decision on the gallery’s part. It conveys that the gallery really belongs to its publics, but at the same time it’s unclear who exactly ends up owning the AGA based on that statement.

So I wanted to make a piece that somehow played with that ambiguity and also played with the idea that the gallery had a character of its own that could reach out and make this indication to a community.

LS: Much of your past artwork—from 2005’s Love Empire to 2011’s Love Locks—has been about public avowals of personal desire, love or relationship. How does that sense of desire connect to what a museum does?

MC: It’s important to remember that at any given institution there are a lot of people involved in making exhibitions happen. And even though all of those motivations are meant to be aligned along a mission statement, it’s useful to remember that those places function because of the very individual and subjective feelings and views of each person who works there. All of them have come together because they believe in art for one reason or another.

LS: Thinking along the lines of passion and desire and your past work, as well as this new project, it came to mind for me that one purpose of an art institution is to encourage admiration or desire or passion for art among viewers. What do you think of that?

MC: Well, I think that’s absolutely true for me. The AGA, which used to be Edmonton Art Gallery, was the first place I learned to love art. I grew up in Stony Plain, about a 45-minute drive from the gallery, and my family used to take me there to see shows from an early age.

I remember seeing a lot of shows there that really fostered a strong love for art. There was a Stan Douglas show that was really meaningful for me as a teenager. I definitely remember an early Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller work there, which, as someone growing up in a small town, really exploded my idea of what art could be on a material level. There was an Attila Richard Lukacs show; it was the first time I had ever heard of an art exhibition with a mature content rating, so that you needed to be a certain age or have a parent’s permission to go. I made sure to see it as soon as I could!

Since I’m also pursuing a PhD in art history, it’s very easy to fall into a pattern of considering art from an analytic, thoughtful perspective that is built around proving something or demonstrating an argument that’s purely about reason. I really believe that art institutions are places for reason and for thinking, but they are also places for feeling, too—for passionate feeling.

I think if art institutions are serious about being places that are about inviting publics to engage, then they need to be willing to allow publics to engage on an emotional level, not just on the level of thought or rationality.

LS: You chose a much more rustic look for this project than you have for past works. Why?

MC: In Alberta, driving the highway between Edmonton and Calgary, I would often see old barns painted with messages—verses from the bible or political slogans or even something as banal as “Store your RV here.” Even though I’ve found some of these messages horrible, it’s a kind of public messaging service that I think is fantastic. I’ve really loved seeing farmers using architecture as a way of communicating something that’s privately important to them.

Also, barns in some ways represent the slow collapse of the agricultural industry. My family comes from farm folk, but most of us are no longer involved in farming. I wanted to pay tribute to that too—to these older social sites, where dances and such used to take place.

So, for this project, I found some salvaged barn material and the font is based on the one used on Alberta Wheat Pool grain elevators.

LS: It’s interesting that the barn architecture you, and likely others, associate with Alberta is so different from the slick, shiny, urban aesthetic used for the AGA renovation. What do you make of that?

MC: Well, I think there’s at least two, but probably more, competing visions of what the future in Alberta will be.

One of them has to do with oil extraction and this constant flow of money and resources into the province, so kind of a vision of constant renewal.

And the other vision is pretty much exactly the opposite, which is to say, well, in the future for Alberta we can’t rely on this resource, we have to diversify what the province is going to be about.

I see that duality at play everywhere in the province, whether it’s in terms of architecture, infrastructure, grocery stores, or restaurants. It’s also in people’s attitudes. When they talk about something as benign as childrearing, it seems to really divide people in Alberta—and probably elsewhere, too. So that’s something I want to think about more.

This interview has been edited and condensed.