I met Margaret Haines before I knew Los Angeles: in New York, in Montreal, and first, through her artwork. The year 2012 was prophesied to be apocalyptic (Greek-rooted, the word means revealing). That’s when I picked up Margaret’s book. Made of leaky-ink newsprint with a perfect-bound spine, the text was a “trailer” for its author’s first, forthcoming film, COCO. COCO—the story of a prismatic psyche born, like Walter Benjamin, under the sign of Saturn—came out in 2014. That movie was set in Los Angeles, like most of Margaret’s latest film, The Stars Down to Earth, and where I live now, thanks in part to Margaret.

She, who was born under an auspiciously Venusian harmony in Montreal in the early ’80s, introduced me to this city as I now know her; did you know the City of Angels is a Virgo? Anybody’s LA is place times time; it’s vision, passage and pace. A rush hour’s detour to drop off dry cleaning. The Getty Research Institute at dusk. Borrowed SUVs or wrecks rented. Democracy Now! podcasts. Kenneth Anger at Starbucks. And a search for the one blue-vein red lipstick at that cottage-awful boutique in Silver Lake. Margaret’s art and person, airily intermixed as they are, cohere in LA, where we are surrounded by stars and other cosmic signs: Universal Studios, Mars Property Management, Venus Art and Flowers, Moonstar Auto Care and Apollo Insurance.

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

Alan Leo, indeed a Leo (born August 7, 1860), was said to be, in the dusk of our Piscean age (that is, of patriarchy), “the father of modern astrology.” He made the ancient study more about psychology, which was then novelly trending. Fame: Leos love it. Alan Leo’s self-sought legacy is “the science of tendencies,” a popularization of astrology as pattern recognition rather than prediction. He wrote many essays on the subject during and after his trials; he was convicted of fortune telling in Great Britain in 1917. What concerns us is what Leo said of the Piscean age, a 2,000-odd year period, ending around now, wherein: “the formalism and external ritual of the priest has taken the place that should be occupied by the spiritual illumination of the prophet.”

The Aquarian age, dawning around now, promises to inspire within every individual an inner knowing such that deferring will be null. All god, no masters. “Your generation doesn’t frequent theatres,” Paul Schrader, Taxi Driver co-writer and director of The Canyons and a hard-to-get Patty Hearst biopic, told me in 2013: “It’s all about portable, or at-home, screens.” Multitasking, screen-capping, YouTube. The Stars Down to Earth, which is 24 minutes long and layered like a trailer, has played most successfully on a loop in galleries and at Amsterdam’s Rijksakademie, where Margaret is presently an artist-in-residence. You can enter in the middle, end, beginning; the narrative holds, new details emerge, patterned upon your recognition.

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

Over voice-only Skype, Margaret tells me that her filmmaking might be “a red herring for research.” She’s written a text to accompany her movie. It’s called Sex Without Threat, after what Theodor Adorno called “the stars” in astrology. “Which means,” Margaret explains, “the stars = authoritarian irrationalism [fascism] and dependency upon a system without recourse or initiative to change this system.” The movie is also named after Adorno. “The Stars Down to Earth” was an essay the German theorist wrote as an expat in 1950s California. He “content analyzed” (ideologically critiqued) a widely syndicated LA-born astrology column by one Carroll Righter, whose ongoing foundation Margaret happened upon while researching the artist Cameron. Stars is partly set in an astrology class that’s based on the foundation. It stars some foundation members. I tell Margaret that this feature in Canadian Art should serve as a trailer. Stills and soundbites from her tight weave. Teasing. Or it’s a paper trail, or a crumby one, a cypher decoder—I’m mapping my way through her school of red herrings.

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

A theme of Margaret’s film and text that even my engineer father would connect to is its equation of astrology’s pseudo-rationality and mathiness to that of financial capitalism, which determines futures by its forecasts thereof. Both are specialized knowledge-pleasure-power plays, sign systems (abstractions), which, endowed with power, are ripe for abuse. “Financial and astrological advice: broadly similar?” Margaret writes in Sex Without Threat. “Both opaque in their initial foretelling but hardcore in their major (life) effects/events: buy, sell, risk…birth, death, fortune.”

Classes take place on Tuesdays at the Carroll Righter Astrological Foundation. “Tiw’s Day” is so-named for a Norse god of War and Law. In most Latin languages, Tues is the day of Mars (mardi, martes, marti), fiery planet of Will and War. In Japanese, Korean, and Sanskrit, too, this second or third day of the week is associated with “fire star” Mars. All days of the Gregorian calendar are coupled with a luminary. Wednesday is Mercury; Thursday, Jupiter; Friday, Venus; Saturday, Saturn; Sunday, guess; and Monday, moon. In astrology, all planets, certain asteroids, and the Sun and Moon hold symbolic meaning, which hold influence over Earth and its beings. Venus is pleasure, glamour, the collective, love. TGIF.

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

I’m invited to join Margaret at the Righter Foundation in mid-August 2014, a couple days after an Aquarius Super Moon, as Jupiter (the Good Luck planet) was quincunxing Neptune (the Guru). One visit, and I’m obsessed. Researching nightly thereon, I learn that what most people know of the Western zodiac is of limited scope. In the 20th century, in order to put astrology into newspapers, this millennia-old system of 12 signs, 12 houses, 10 planets, plus asteroids and nodes, everything with an individual chart, ever-shifting for the ongoing transits of celestial bodies, was reduced to: horoscopes. Predicting one’s day or week like the weather. Categorizing people into 12 types. You are your Sun Sign. Which is basically, the Ego, our go-between individual needs and social expectation. This is a 20th-century, ascendant-American figuring of being. “The Century of the Self.” You are a hippie, a hipster, a square or queer. Sunny, chance of showers, female or male. Scorpio, Cancer, Aquarius. Little boxes all the same.

I recall, from the interior of the Righter Foundation: sun-bleached family photographs and piles of American Flag–print Beanie Babies, a checkerboard floor, marble, Styrofoam cups, a butler. No one we were with lived there. Righter specified in his will that whomever possesses the mansion must let his followers use it at least once a week.

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

Another theme of Margaret’s text and movie is another meaning of star. Celebrity. Heroine. We see Henry Hopper, son of Dennis, hopping between five-pointers on Hollywood Boulevard’s Walk of Fame, as in a child’s superstitious game. We see Afia Fields, as the god Apollo, beating her arms against a blue Mustang. “I’m the star!” she expounds. Henry’s in the driver’s seat. The class charts Edward Snowden’s birth. His fame—notoriety. All motion pictures contend with Hollywood, with its formulas and hierarchy (A-list, B-list, pornography). It’s still a recent history. Margaret cast Henry as Cassandra, a mythic prophetess discredited within her nation, like Snowden. Henry plays Cassandra, not hysteric like Jungian analyst Laurie Layton Schapira would have her, but rather, wall-eyed and entitled like Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver. As in that Hollywood classic, part of the “American New Wave” father Hopper’s ’69 hit Easy Rider propelled, Margaret’s film ends with a girl and a gun—with this thwarted young man’s testing fate. “When you do something bad,” Margaret explains, “you know what the outcome will be.” “Yes,” I respond. “Violence is a sure-fire way to become at least a little bit famous.”

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

Are followers of astrology dispossessed? Marginalized citizens grasping for meaning? A 1976 San Francisco–based study suggests as much. “We found,” the authors write, “the greatest commitment to astrology among the less well educated, blacks, and women—all of whom have been recognized as relatively deprived of the power, prestige, wealth, and other rewards which society offers.” Later, they detail us, believers, further, as: “the more poorly educated, the unemployed, non-whites, females, the unmarried, the overweight, the ill, and the lonely.”

Everything speaks. Sound, texture, gesture. In Margaret’s movie, even colour. Pink and blue. “Blue for the throat chakra, blue for the sky, blue for the crown chakra, blue for depression, and blue,” Margaret writes, “for the medieval alchemical decision to pit the human body in the same place as heaven—as above so below.” Rosie, my editor at Canadian Art, asks: “Is it about gender?” I tell her that as long as I’ve known her, Margaret has worn this Hot Topic pink, and as for blue? Blue is the ocean and rare in food and still America’s most popular favourite colour. And it is Los Angeles. Our sunsets are so iconically pink and blue, extra-vivid for the pollution, that artist Alex Israel, a Bret Easton Ellis collaborator, has made them his saleable signature.

“After 5 years of attending the class,” Margaret writes. “I believe astrology is real, as real as life and the panic of falling in love, as mysterious as the body tissue sanctifying emotion and holding memories for future ailments and cancers.”

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

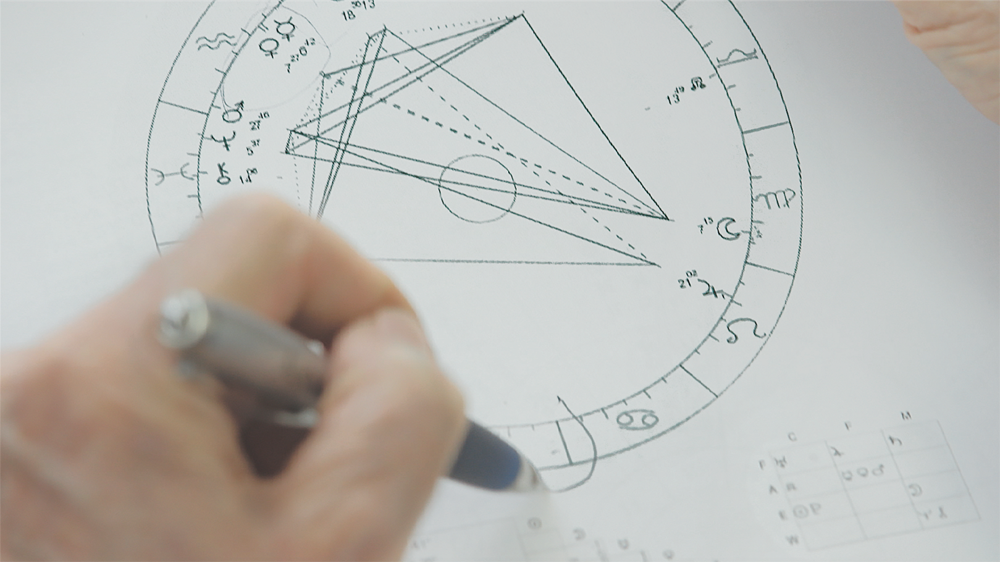

Birth charts are round, like a clock, a target, a roulette wheel, the planets, areolae and eyes. Everybody has a birth chart. Everything, too, they teach you at the Righter Foundation. Jack Taub, an instructor there, draws up charts for cars, pets, cities. Los Angeles is a Virgo. Toronto, a Leo. Jack calls astrology “the study of time.” Tom Kaypacha Lescher, my favourite astrology vlogger, says it’s “the study of cycles.” Revolution means to roll back. Women cycle with the moon. Folios, grid calendars and all our screens box us in, punishingly Apollonian in their order.

Maybe it is about gender. The myth goes like this: Greek beauty Cassandra was gifted true foresight by reasonable God Apollo. When she refused his command to have sex with him, conceding to just one kiss, he spat in her mouth with this curse: everyone will doubt her prophecies. “If only you believed,” Afia tells Henry. What if all that’s given is choice? Astrology’s most empowering myth, to me, is that we choose our own adventure. We, souls immortal, select the time and place of our births, and with that, a mutable destiny is fixed with predilections and impediments. Margaret and I chose our Canadian motherland, just as we chose to move to and from LA in the 21st century. And just as I, at this stage in my game, would rather play with the starry-eyed than with financiers.

The Stars Down To Earth Trailer from Mags Haines on Vimeo.

Fiona Alison Duncan is a peripatetic Canadian-American writer and artist, and a Scorpio Rising—for better or for worse. A featured columnist at Kaleidoscope and Adult magazines, she also writes regularly for Bon, Mel and Sex. She can be found online at @fifidunks or try: fionaad.com, aural.us and unknow.in.

This post is adapted from an article in the Winter 2017 issue of Canadian Art.

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.

Margaret Haines, The Stars Down to Earth (still), 2016. Film, 24 minutes.