“We didn’t collect photography, photography collected us,” Harry Malcolmson says, with the complete agreement of Ann, who adds, “Yes, I like that phrase.” Their collection, which now numbers more than 200 photographs, along with rare negatives, albums and books, is one of the most important private collections in North America. Its particular relevance as a collection that covers the entire span of the medium, from prints by William Henry Fox Talbot to a film by Mark Lewis, seems especially pertinent in Vancouver, where an exhibition of 110 photographs and objects closes December 20 at Presentation House Gallery. This first public-gallery exhibition of the collection affords particular insights into the work of Vancouver photoconceptualists in its rare juxtapositions of very early photographs and very recent contemporary art, and in a broader sense tells us how the medium’s history informs its present.

The Malcolmson collection might be the only one in private hands to produce an exhibition, expertly curated by Helga Pakasaar, in which a Charles Marville albumen print of a narrow cobblestone Parisian street, photographed in 1876 or 1877, hangs beside a mixed-media work by Vancouver photoconceptualist Ian Wallace, made in 2008, that is strikingly similar in subject matter and composition. Down the wall, there is a photogravure of Glasgow slums by Marville’s Scottish contemporary Thomas Annan, whose photographs were a direct influence on Wallace’s seminal work Poverty. In the same gallery, Ricking the Reed, an 1885 platinum print by Peter Henry Emerson, an important reference for Scott McFarland, is juxtaposed with his Empire 5, a colour inkjet print from a 2005 series on cacti at the Huntington Botanical Gardens. McFarland and Wallace have steeped themselves in the history of photography, which underlines their work in much the same relationship that it has other Vancouver photoconceptualists like Roy Arden, whose work is also owned by the Malcolmsons.

The couple began collecting around 1959, not long after they were married. Neither had collected art before, but together they had adventurous inclinations from the start. “I guess we didn’t know what we were supposed to do,” says Harry, underplaying their acumen and their attraction to the most current art. Their first purchase was an abstract painting by Montreal artist Paul-Émile Borduas, a leading member of the Automatistes, which they bought from Douglas Duncan. Ann recalls, “It was a major step.” They bought the work of young painters associated with the Isaacs Gallery, like Michael Snow, Rick Gorman and John Meredith. And they looked to the international scene, buying original prints by Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, Richard Serra and Bruce Nauman.

They hung the Naumans, five screenprints from the 1970 suite Studies for Holograms in which the artist manipulates his lips into grotesque images, in their dining room until the protests of a close relative brought them down. Their 13 prints by Richard Hamilton included images that became icons of a decade: Swingeing London 67, based on a press photo of Mick Jagger and art dealer Robert Fraser’s arrest for drug possession, and Kent State, a screenprint of a student slain at a campus protest by a member of the National Guard, made using a photograph of a TV screen and issued in an edition of 1,000. Prints like these, Harry says, brought “an early rumour of photography” to their collection.

Interestingly enough, it was their first encounter with photo-based art in New York, in 1985, that brought them to photography. Ann’s interest was piqued by an exhibition of the British artist-photographer Craigie Horsfield, which Harry remembers as “dry, impersonal exteriors of UK institutional environments, such as hospitals and universities, rendered in quite dark tonalities.” Ann was intrigued by what history might lie behind it, while Harry had “an intuitive sense that there was something there [in the medium] that was amazing.” He says, “We were ready for something fresh and new, adventure, exploration. There was a pull, a gravitational thing, I guess. I was amazed that the deeper in we got, the more intrigued we were. We were encountering so much complexity and diversity.”

When the Malcolmsons decided to change focus, they “made a clean sweep” and divested themselves of their first collection. Their first photography purchase was The Steerage by Alfred Stieglitz, a 1907 photogravure considered to be this early modernist’s signature image, in which he moved from the mists and symbols of pictorialism to a more reality-based style. They bought the Stieglitz from Toronto dealer Jane Corkin, who had a significant influence on their early collecting. “Jane gave us access to Kertész,” says Harry, and to other photographers like Tina Modotti and Edward Weston. The collection now contains five Kertész photographs, which includes 1929’s Street Work, a striking composition that shows a labourer silhouetted against deep, indistinct background space defined by two large pipes set on a diagonal. It is an unusual image for Kertész, and it is arrestingly beautiful.

The Malcolmson collection is not a comprehensive or textbook reiteration of photography’s history. “It’s our history,” Harry says. The collection is characterized by its concentration on periods of intense creativity, experimentation and innovation, which include the 1850s and 1860s, the 1920s and 1930s, and the present digital era. Much of its personal character and lively visual chemistry derives from its combination of exceptional, iconic-image prints by important photographers—like Édouard Baldus, Gustave Le Gray, Eugène Atget and Paul Strand—and photographs that are completely unexpected because of their process and subject, or because of the circumstances under which they were made. The latter includes a blue-toned bromide print of a paper cut-out chorus line by the Czech Frantisek Drtikol from 1930, as well as the barely there human face captured the same year via a radio broadcast from the Eiffel Tower, one of the earliest experiments in the development of television in France. The latter was an acquisition in which, Harry says, “I was following in Ann’s footsteps.”

“The collection is molded by Harry’s eye and interest in what makes a good photograph, the art qualities that make a good photograph,” says Ann. “I am more interested in the texture of the paper and the subtleties of toning, but we are both interested in the mysteries and indefinable qualities of works.” They also have favourites among photographers. Harry is an enthusiast of Bill Brandt, represented in the collection by nine images; Ann’s passion is for Man Ray, who is represented by eight photographs that demonstrate the range of his virtuosity as an artist-photographer. One of her favourite photographs in the collection is Man Ray’s Eyes from 1935, a photographic image of seductive eyes above a delicate graphite drawing of the nose and mouth.

The Malcolmsons’ individual enthusiasms make them a very good team. Harry’s keenest interests are in the formal aesthetics of photographs; he cares less about a photograph of architecture than he does “the architecture of the photograph.” Ann’s concerns are more deeply involved with the materiality of photographs and their object qualities, which have to do with such things as the particular process, the paper support and the photograph’s tonal range. “We found that you have to do more research to be a sensible photography collector,” says Ann. “Photographs require a lot more study and detail . . . Each print is so different.” She has observed, for example, that both Brandt and Weegee reworked lines in their prints with a pen. And she has learned the crucial difference between vintage and later prints. The Malcolmsons are interested only in vintage prints and have honed a standard for judging their quality.

The Malcolmsons had been collecting modern and modernist photography for several years when they did another about-face and seriously began to collect work from the early history of photography. As in their encounter with Craigie Horsfield, their desire was to go deeper into the history of photographs and photographic processes. Along with Fox Talbot, Baldus and Marville, the collection holds prints by other major early figures such as Hill and Adamson, Charles Nègre, Louis de Clercq, Maxime du Camp, John Beasley Greene, Roger Fenton and Julia Margaret Cameron. The concentration here, mostly in the 1850s and 1860s, is a period of rapid change, says Ann, in which the technology “went from salt paper negatives to glass negatives and from salt paper prints to albumen prints.”

Among the collection’s treasures is a salt paper print by Nègre, 1857’s Saint Gilles du Gard and its calotype negative. Both the positive and the negative were shown in Canada in 1976 in the exhibition “Charles Nègre,” which was curated by James Borcoman at the National Gallery. “We bought them and brought them back to Canada,” says Ann. “We were thrilled. They are a very important part of the collection.” Altogether the Malcolmsons have acquired six negatives, which Ann believes it is important to collect because they are unique.

Only the collection of Vancouverites Claudia Beck and Andrew Gruft, given to the Vancouver Art Gallery in 2005, matches the breadth of interests displayed by the Malcolmson collection, which offers, in addition to things already mentioned, several avenues to follow. A group of surrealist photographs includes Hans Bellmer’s oddly menacing 1937 exposure La Poupée, which has startling human legs on the bottom and doll legs on the top. There are press service photographs and others documenting historic events or people, like the anonymous Hitler at Potsdam from 1936, Margaret Bourke-White’s candid portrait of Stalin’s great-aunt and William Saunders’ 1880s albumen print Execution Grounds, China, in which officials pose behind a row of bodies whose severed heads lie beside them.

There are nudes by Heinrich Kuhn, Frantisek Drtikol, Man Ray, Bill Brandt and Harry Callahan, which span 1906 to 1954, and Edward Weston’s sexy White Radish of 1931, which only resembles a reclining female nude. As well there are sensuous currents running through images like Man Ray’s 1920s print Hand in Hair and an upside-down 1930s portrait called Blonde by Jaroslav Fabinger, which echoes the posture of Weston’s 1920s blonde Nahui Ollin.

The Malcomsons were invited to show their collection several times before, but they declined because they wanted to wait until they felt it was mature. Achieving maturity, however, does not mean that they have acquired their last photograph. On the contrary, Harry describes the collection as “200 photographs and counting.” Ann remarks that they are looking for completion in some ways and points to purchases this year of an 1858 portrait of a bearded man by Nadar as well as two calotypes by Eadweard Muybridge from 1887’s Animal Locomotion, works by photographers who were previously missing from the collection. There are other things on the Malcolmsons’ desiderata list. Harry would like more photographs by Manuel Álvarez Bravo, the great Mexican modernist, who Harry believes is underrated. Ann will surely go on to find new and innovative twists in the career of Man Ray. After all, passionate and committed collectors like the Malcolmsons never really want to write finis on their creation.

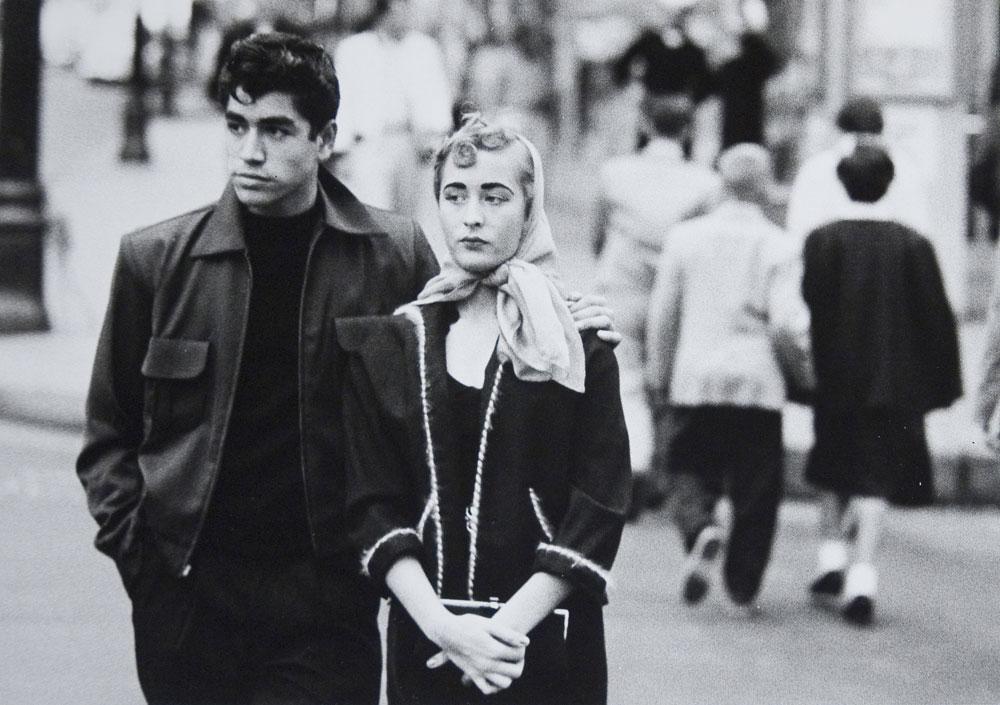

Robert Frank Chattanooga, Tennessee 1956

Robert Frank Chattanooga, Tennessee 1956