His art has been exhibited at the British Museum in London, the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris and the Grenada Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

But he lives in the Headon Forest subdivision of Burlington—with a basketball hoop parked in the driveway and a sprawling suburban parkland at the end of his street.

These are some of the worlds spanned by Mahmoud Obaidi, an Iraqi-Canadian artist currently showing in a critically acclaimed Istanbul Biennial curated by Berlin art stars Elmgreen & Dragset.

“I want to show in Canada, because I have this huge relationship with it—it is my home,” Obaidi tells me.

But it is still unclear when galleries in Canada might actually take up his work.

Obaidi has shown at the Venice Biennale multiple times, most recently in a group exhibition at the Grenada Pavilion. This summer and fall, his art was also on view in the exhibition “Living Histories” at the British Museum, where it is part of the collection. Ubercurator Hans Ulrich Obrist interviewed him for the catalogue of Obaidi’s 2016 show “Fragments” at the Qatar Museums.

And yet, Mahmoud Obaidi’s artwork remains little exhibited in the country where he has made his home, off and on, for more than two decades.

Mahmoud Obaidi’s sculpture Ford 71 (2015) in his recent solo show “Fragments” at Qatar Museums. Photograph: Sahir Uğur Eren.

Mahmoud Obaidi’s sculpture Ford 71 (2015) in his recent solo show “Fragments” at Qatar Museums. Photograph: Sahir Uğur Eren.

Interestingly, much of Obaidi’s art speaks directly to issues of home, displacement and belonging.

Obaidi has experienced such displacements himself—displacements driven by invasions of his home country of Iraq, where he was born in 1966 and graduated from Baghdad Academy of Fine Arts in 1990.

“I left Iraq in ’91, and basically couldn’t go anywhere,” he says, conversing over espresso in his Burlington living room. “I went to around 10 different countries,” he says, but couldn’t gain residency.

After short-term stints in Thailand, Jordan and other nations, Obaidi secured immigration to Canada, where he studied film at Ryerson University and earned an MFA from the University of Guelph in 1998.

Obaidi calls the teachers at his Canadian schools “fantastic,” but after graduation he found it easier to maintain studios and production abroad than at home.

Sculptures for his Qatar show last year, for instance, were made in Hong Kong and Italy. Many are still stored overseas. For many years, he has also lived and worked intermittently in Doha.

“I’m trying to get back here in a way that I would work here,” Obaidi says of Southern Ontario, noting he is currently trying to explore the possibility of moving his studio to nearby Hamilton. “I have some works that are 10 metres tall, so I’m not sure how it’s going to work here. I’m going to try with smaller pieces here and I’ll take it from there.”

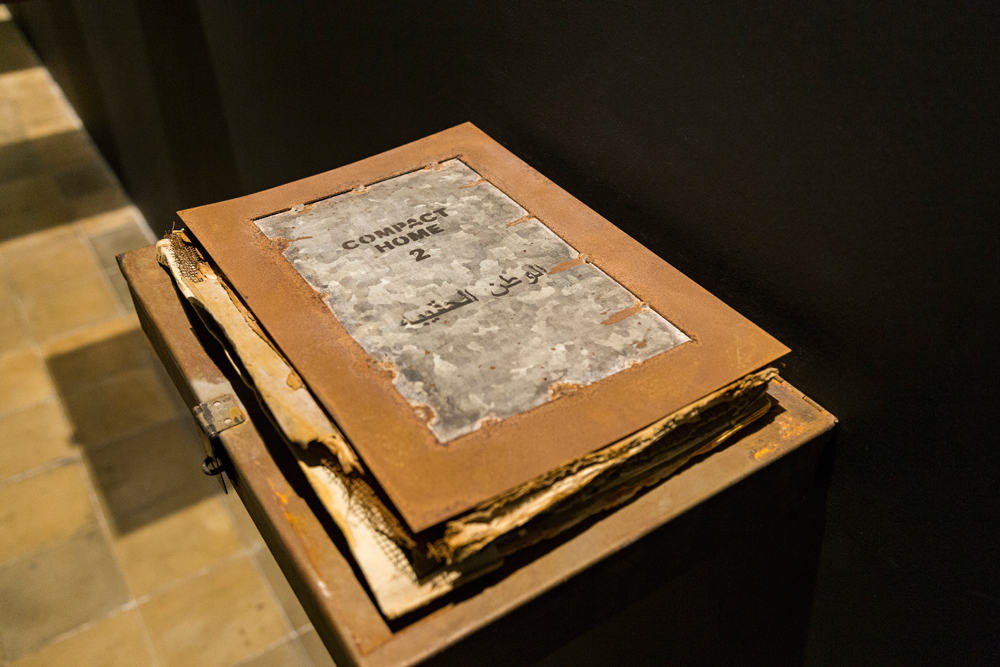

Mahmoud Obaidi’s Compact Home Project (2003–04) on view at the Istanbul Biennial. Mixed-media, eight metal boxes containing metal books, each 35 x 24 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photograph: Sahir Uğur Eren.

Mahmoud Obaidi’s Compact Home Project (2003–04) on view at the Istanbul Biennial. Mixed-media, eight metal boxes containing metal books, each 35 x 24 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photograph: Sahir Uğur Eren.

Though Obaidi’s massive sculptures are certainly compelling—his Assyrian winged figure in a pickup truck, titled Ford 71, is what he says initially attracted the attention of Elmgreen & Dragset—his smaller works pack a punch.

Obaidi’s Compact Home (2003–04), for instance, which is currently on view at the Istanbul Biennial, is tiny in size but big in impact.

Each of the small metal “books” in this series compiles fragments of Obaidi’s life during his forced displacements—a series of years when, as he says, he didn’t want to acquire anything “Because I thought, I’m going to have to lose my stuff again and again and again.”

If he read a novel during this time, for instance, he would throw it away after reading—but keep the title page. Such fragments are what ended up in Compact Home’s tomes.

“I had this plan that I go back one day to Baghdad to have my studio there,” Obaidi says. “But in 2003, because of the invasion of Iraq, I knew [that dream] was gone.”

So he took all these pieces of material he had been gathering and put them into the metal boxes or covers that would become Compact Home.

Another “smaller” project of Obaidi’s that has affected many viewers significantly is Fair Skies.

A continuation of a prior project called How to Not Look Like a Terrorist in the Eyes of the American Airport Authority, Fair Skies is premised on the idea of installing vending machines outside of airports that dispense kits for bleaching hair, whitening skin, inserting blue contact lenses and altering other racialized features.

Like several of Obaidi’s other works, Fair Skies derives from his own personal experience—in this case, the experience of being repeatedly detained at airport security due to racial profiling, even when travelling on a Canadian passport.

One time in particular, he says, such a detainment happened when he was waiting for a flight from Texas to Holland. A security officer saw him in a lineup of Nordic blondes and asked to see his passport. The result was a two hour ordeal.

“When I reached Holland, I talked to my wife,” Obaidi recounts. “I said, ‘I have to do something about my look!’ And I was joking. But then I did this project.”

Earlier this year, Fair Skies was exhibited at Mathaf, the Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha. Prior to that, in 2012, it was included in a 25th anniversary show at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, and in 2010 it was exhibited in a group show of Iraqi artists at Leila Taghinia-Milani Heller Gallery in New York.

An awareness of who dominates tales of global history, and who exercises power within it, also came up in Obaidi’s project “The Imposter” (originally called “The Replacement” during its initial run at Meem Gallery in Dubai) which was featured as an official collateral event at the 2015 Venice Biennale.

For it, Obaidi created magazine covers, T-shirts, dinner plates, newspaper clippings, letters and other ephemera related to a person who was supposedly being groomed by the West to take over the leadership of a Middle Eastern country.

Though the persona Obaidi was constructing in the show was fictional, its inspiration was firmly rooted in reality—namely, in the decades that Western nations have spent intervening in Middle Eastern politics. And in the way Western media has reshaped the Middle Eastern story.

“I think art is important because we are documenting things in our own way,” says Obaidi. “Then, in a hundred years or a thousand years, people will be able to see through this paradox: ‘Oh, the news says this. But the artists say that.’”

Mahmoud Obaidi’s Operation Iraqi Freedom Family(2016), on view in his Qatar Museums show “Fragments,” is made of recycled American weapons and Humvees used in Iraq mixed with bronze. Photograph: Sahir Uğur Eren.

Mahmoud Obaidi’s Operation Iraqi Freedom Family(2016), on view in his Qatar Museums show “Fragments,” is made of recycled American weapons and Humvees used in Iraq mixed with bronze. Photograph: Sahir Uğur Eren.

What’s next for Obaidi? In addition to checking out those possibilities of moving his studio—10-foot-tall sculptures included—to Hamilton, there’s also some curatorial projects.

Currently, Obaidi is working on curating a show of Toronto-based Iranian artist Sara Niroobakhsh at CICA Museum in South Korea, as well as a show of Iraqi-American artist Nazar Yahia at Mark Hachem Gallery in Beirut.

Other than that, for the moment, Obaidi is, as he says, “off for a few months.” (Obaidi identifies himself as the kind of artist who works intensively for periods of time, then takes time off from artmaking completely.)

So now there’s more moments, perhaps, to practice a lay-up on that basketball hoop in his Burlington driveway (it’s mostly for his teenaged son), or go antiquing in Freelton or other spots nearby (he and his wife have outfitted their contemporary home with many Southern Ontario retro finds).

There’s also time to mull over realities that still flummox him about the Canadian art scene.

“I have some friends here, and they see it as insulting for artists to be part of the market,” Obaidi says. “But without the market, I cannot have a studio. I cannot produce works. Every time I sell work through the market I can create another piece, actually.”

And beyond that, there’s still the conundrum of, always, parsing the idea—and reality—of home.

“I discovered that there are many homes on the planet,” Obaidi said in a 2013 interview with Qatar artist Karim Sultan. “This peaceful part of me I got because of Canada, and the Canadian passport…I want to give back to that society and start something there.”

Mahmoud Obaidi’s Make War Not Love, Chapter 4, (2013–15) is on view at the Istanbul Biennial. Mixed-media on canvas, 257 x 247 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Mahmoud Obaidi’s Make War Not Love, Chapter 4, (2013–15) is on view at the Istanbul Biennial. Mixed-media on canvas, 257 x 247 cm. Courtesy of the artist.