When David Milne learned of the existence of the Canadian War Memorials Fund in December of 1918, he was at the end of a two-week furlough in London. He had been training for service at Kinmel Park Camp in north Wales when the armistice was declared, but was keen to stay on in Europe, to travel and paint after his nine-month hiatus from making art. Within weeks, Milne had made his case: notwithstanding that the war was over, he would record the training facilities that had served as a home away from home for Canadian soldiers stationed in England. As well, he would paint the now-stilled battlefields of France and Belgium, where his countrymen had died by the tens of thousands.

Milne crossed the English Channel to Boulogne-sur-Mer on May 17, 1919, and was assigned a driver and accorded the privileges and access of an officer, with all of his quotidian needs seen to. The months that followed were passed in a kind of cultivated solitude, and were the most materially productive days of his career.

The 67 watercolours he painted during this period have long been beloved by Canadian art historians—from David Silcox and Rosemarie Tovell to John O’Brian—yet they remain lesser known to the wider public. This is no doubt due, at least in part, to their grisly subject matter, which is so coolly contemplated; like Colville, who served as a war artist in Europe in the aftermath of the Second World War, Milne kept an unnervingly steady pulse in the face of death and destruction. But the obscurity of these works may arise as well from their radical modernism; these watercolours are more austere than his softer and more easeful landscapes and delicate still-life studies. Here, at the turning point in painting’s history, with abstraction rising to challenge the traditions of representation, Milne posited a visual field that is in many cases just a shimmering skein of dry strokes, little microchips of colour that shower down to suggest the blasted churches and bunkers, the pitted roads and the blown-out vistas where towns like Courcelette and Passchendaele had once stood.

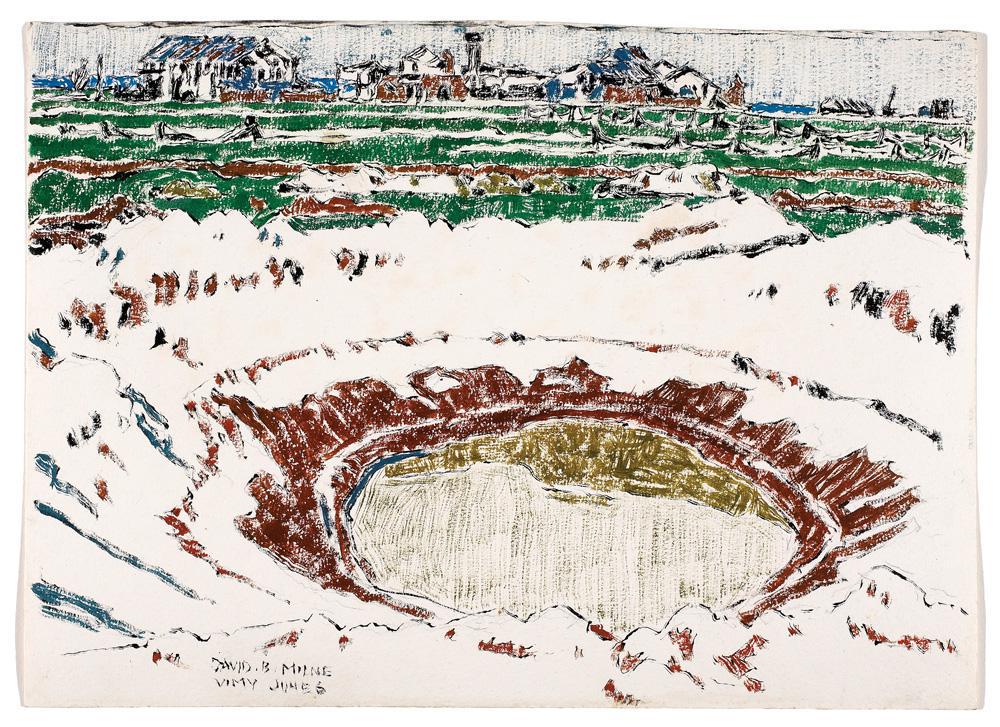

One of the more striking of these is Milne’s watercolour Montreal Crater, Vimy Ridge, painted on May 27, 1919. It is, quite literally, a picture of nothing—a record of a monumental visual vacuum where once there had been land. Here, the German lines had taken heavy hits from Canadian and British mines that had created massive pits that were, as Milne noted, “deep enough to hold a house or even a church.” Over the course of just five hellish days, in April 1917, some 3,598 Canadians had been killed at Vimy Ridge, with more than 7,000 men wounded.

Observing the scene under spring skies, just four months after the final cessation of hostilities, Milne described how “the earth had been torn up and torn up and torn up again,” adding that, “at every step rifles and bayonets and twisted iron posts and wire projected.” All around him lay “a litter of shell fragments, cartridges, shell cases and dud shells big and little, web equipment, helmets, German, British, and even in some places French, water bottles of three nations, boots and uniforms, the boots often with socks and feet in them. Some shell holes even on top of the ridge had water in them,” he continued, “and, over all, the sweet sickish, but not offensive, smell of death.”

As was Milne’s daring custom, the blank surface of the paper was deployed as an active compositional player, with the eye drawn from fleck to fleck of colour, reconstituting meaning from these subtlest of cues—touches of slate blue here, nascent vegetative greens and tobacco browns there, all of it punctuated with traces of jittery black. On the brow of the pit, two tiny, uniformed figures are barely discernible commencing their exploratory descent. The scene is less dramatic, perhaps—more cerebral and reserved—than some of the more flamboyant evocations of wartime trauma the era gave rise to. Yet Milne’s watercolour registers a new understanding of mankind’s suddenly fearsome destructive capacities, and a commensurate new way of seeing, one that registers information without imposing an overarching visual certitude. It’s a picture of instability, of verities unhinged, in a pictorial style that Milne once described as “tumbled flatness.”

Milne long recalled the silence that served as the backdrop to his days in the fields of France and Belgium, a stillness punctuated only by the occasional unexpected detonation of found munitions, the distant bugle calls at ad hoc field burials or the murmured marching chant of a troop of German prisoners of war being escorted between detainee camps. One wonders how this interlude haunted his later life, perhaps serving as a remembered counterpoint to the tranquility of Bishop’s Pond near Boston Corners, where Milne returned after the war. Here he would make his celebrated series of mystical, wet-into-wet mineral-toned watercolours of still water edged in trees, pictures that offer sanctuary from mankind’s modern fall from grace. Other paintings, like his studies of an abandoned iron mine at Temagami, made a decade later, feel like flashbacks, willfully awkward and chaotic compositions that reveal the clumsy hand of man wielding force where nature alone had once prevailed. “The man changes,” Milne once said, describing his struggle to get down on paper his experience of those ravaged battlefields and ruined architectural remains, “and with that, the painting.” How could it be otherwise?

This is an article from the Summer 2014 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, visit its table of contents. To read the entire issue, pick up a copy on newsstands or the App Store until September 14.