When I went to Vancouver earlier this year to interview Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun for this magazine, I thought it was a good assignment. Yuxweluptun is articulate and loquacious, but conversations with him can be challenging. In part it’s because his subject matter is so troubling: the colonialist suppression of First Nations cultures, the occupation and systematic destruction of the natural environment, self-governance and the politics of land claim negotiations. These issues invariably provoke vehement pronouncements.

There was also an added layer of difficulty in this instance because I wanted to talk about painting, a topic that Yuxweluptun diffidently shrugs off as merely “an exercise of skills and personal style.” While skill and style are abundant in his artistic output, there is more to say. Yuxweluptun’s skills and style coincide with and reciprocate his subject matter in ways that are both playful and full of critical insight.

With almost 30 years of art making to his credit, there is already a lot about Yuxweluptun’s work that will be familiar to contemporary art audiences. He calls himself a history painter and, as if claiming their place within the academic canon of history painting, his large-scale figurative landscapes employ a standard composition—a composition also seen in the pictures made by missionaries and soldiers recording the findings of early European settlers in Canada. The intense palette of the landscapes seems quite singular and initially puts one in mind of the glowing colours of a digital screen, perhaps inspired by video games. But an intense palette can also be found within the Canadian landscape tradition if one looks at the lurid snowscapes of Suzor-Coté or, as Northrop Frye has described, the “strident colouring” of Tom Thomson’s “twisted stumps and sprawling rocks.”

It has been said that Yuxweluptun uses the entire Canadian landscape tradition as an archive from which to construct a counter-narrative to the familiar one that links psychic possession of the landscape with the construction of a national identity propagated by the Group of Seven, though in a more general sense he takes issue with the popular myth that Canada was carved out of the wilderness. In Yuxweluptun’s world, the land is never unseen or unlived in. To make it so means dispossession for his people. Unlike Group of Seven works, his landscapes are always populated with figures who are usually engaged in activities that express their relationship to the land. “We have a saying,” he jokes, “that nothing is ever found until a white man names it.” The bitter punchline: “But it was never lost to us.” One history to which his paintings bear witness, then, is the dark and pathological underside of national identity.

Stylistically, the works are most frequently noted for two distinct and seemingly incongruous features. Yuxweluptun’s Surrealist borrowings are striking. It is hard to miss the Dali references in his melting forms and quixotic imagery. We are reminded of the Surrealists’ wholesale borrowings from Native American art in search of a direct route into the subconscious. Turning the tables, Yuxweluptun reappropriates those Surrealist tropes, adroitly putting the lie to their attendant presumptions while retaining all of their pop culture allusions to the psychic landscape.

Equally striking is Yuxweluptun’s use of ovoids, formlines and other design elements from Haida and Kwakwaka’wakw art. Yuxweluptun is Coast Salish, which sets him apart from traditional ethnic authority for their use. But again the tables are turned, in this case calling into question both the modern craft revival of a traditional vernacular and the market in Northwest Coast souvenirs. Nonetheless, his usage asserts that, far from the primitive savages of Surrealist (and colonialist) myth, Native Americans were practicing a highly sophisticated art with a rigorous symbolic order. By appropriating the Haida iconography himself, Yuxweluptun not only questions that traditional authority but also makes it apparent that the problem with the Surrealists’ appropriations was not so much their unauthorized use as their failure of understanding.

In the meantime, combining the stylistic conventions of Surrealist and Haida art has the effect of flattening the distance between opposing views. Both Haida design elements and Surrealist imagery are transformed, via their route through pop culture, to become Yuxweluptun’s “neo-Native” style. He likens these dual streams of reference to simultaneous translation between one culture and another. But he also asks, “Why in the hell carve a welcome figure? This is what being under occupation is about. Under occupation, I don’t have that right. Maybe only the premier of the province or the prime minister has the right to carve a welcome figure.” With this thought we can interpret his appropriations of Haida imagery as an angry lament for the loss of language and culture suffered by Native people.

Land use issues are the dominant subject matter of Yuxweluptun’s landscapes. Indian World My Home and Native Land (2012) goes to the heart of this concern. The vertical format of the picture emphasizes the strong verticality of the trees, which are still firmly rooted in an otherwise fluid and shifting ground. The clouds contain suggestions of animate shapes and, eventually, the eye discovers a tiny, almost ghostlike human figure in the foreground. In the face of overlapping and conflicting interests—private property, commercial interests, resource extraction, provincial parks, federal parks—the Native person stands his ground. Yuxweluptun is not prepared to surrender his sovereignty: “We are not extreme people. We are very rooted to our traditional and sacred lands. This painting, Indian World, is about who is the caretaker. Who owns this land? These are our homelands. I am not willing to give this land, my motherland, to the province of British Columbia. Why do I have to extinguish my rights? Why is there this colonial extremism?”

Yuxweluptun has produced a number of works that depict ritual or ceremonial activities in longhouse interiors. Similar in style and scale to the landscapes, they elicit a different mood—more sober, less worldly. Yuxweluptun’s skills as a colourist come to the fore in these pictures. His palette is more subtle and subdued, using colour to model the space theatrically, with occasional flashes of a brilliant hue in a dancer’s mask or a drum skin. It is hard to imagine the anguish of a people whose rituals of worship have been outlawed. “This is a very creepy country that thought it was their God-given right in history to outlaw Aboriginal potlatch,” he fumes. With equal parts reverence and celebration, Yuxweluptun argues for the legitimacy of Native styles of worship. Referring to Floor Opener (2013), he tells me, “I made this painting to settle the question of the unknown, the fear of the Other.” Keeping in mind that an important part of potlatch is the transmission of knowledge through story, song and objects, I am struck by his comment: “I can dance and kai-yai around the fire and when I leave the longhouse it’s still there, it’s all sacred, it’s still Indian land.” As history painting, his pictures participate in that function of longhouse ceremonies, sharing stories and objects to keep memory and knowledge alive.

Many of the landscapes depict tree stumps and clear-cuts and, most notably, trees. Yuxweluptun’s oeuvre celebrates trees. Composed of stylized feathers, porcupine quills, salmon heads and the omnipresent ovoid, these trees are yet unmistakably the indigenous species of spruce and cedar of the Northwest Coast rainforest. Yuxweluptun admits to being a tree hugger and in our conversation his fiery words against the Christian church are calmed for a moment when he says, “I would rather raise my kids in a different way and talk to them about the world in a different way. I want to talk to them about how sacred the trees are.”

It is this feeling that lends a sense of worship to his drawings of trees. They come out of the joy and affirmation derived from his experience of the forest. These images are where he uses his graphic skills to play most freely with pattern and design. Through repetition and variation of his sinuous line, the shapes grow and mutate across the page. The more they approach the condition of an overall pattern, the more they convey the sense of the all-encompassing closeness of the forest. This is not the mournful, claustrophobic closeness of Emily Carr. In Yuxweluptun’s hands, fulfilling his desire to tell “what it feels like to be a Native,” the forest is active, inhabited by life-giving spirits, always present, continuously transforming. Beyond the politics of Environment Canada, Yuxweluptun adamantly states, “There is only one Earth. It is very disheartening to stand in a clear-cut, but you grit your teeth and look at all these things and, you know, I’m still going to pray here.”

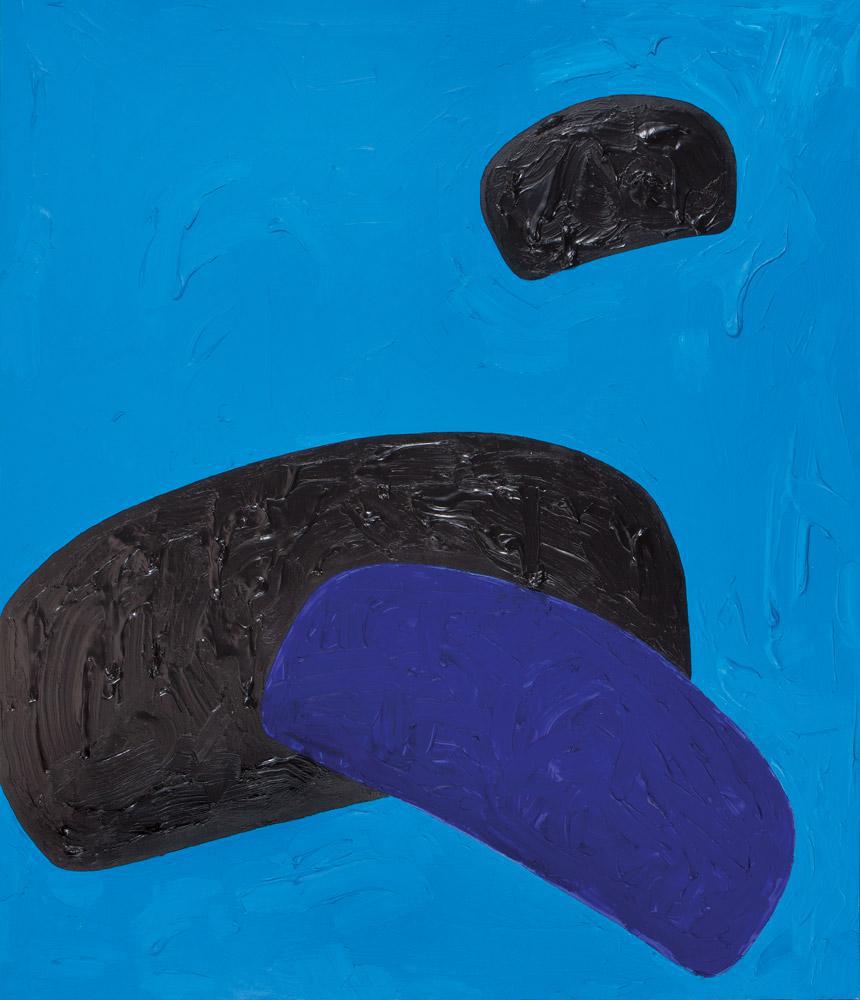

Yuxweluptun’s abstract paintings can seem off-kilter with his figurative works but, in fact, they share features. Dubbed “Ovoidism” by Yuxweluptun, the works employ the figure of the ovoid, although here, it is the sole graphic element. He also uses a more limited palette in the abstracts and, unlike the smooth surfaces of the landscapes, the paint is applied in a relatively thick impasto. The art historical references are often quite distinct, frequently reminding one of Paul-Émile Borduas and the Automatistes. Like their Surrealist forebears, the Automatistes were also striving to tap the creative stream of the subconscious.

I tell myself only half-jokingly that Yuxweluptun subconsciously embraces them because, like him, they rejected the Catholic church. He characterizes his approach to the abstracts as purely intuitive, often without preliminary design. “I have fun making them,” he tells me. “There is an intellectual process of balance, design, colour, that comes out of just being. I like all the things about creating a neo-Native gaze. When you’re so busy being oppressed you have to take the time out to enjoy your own life. So it’s not always a bad colonial day. I’m having a good Indian day when I’m making. A good Indian day is a good day to be, to create.”

The best of the abstracts convey this sense of untroubled aesthetic pleasure, but the ovoid, with its weight of cultural significance, extricates them from the alibi of autonomous form that so much modernist abstraction laid claim to. Yuxweluptun sees this as a part of the process of emancipation: “I may have a bad colonial day and I will take that out in my painting. That’s my solution. Through my whole life, rather than standing on a blockade and getting nowhere and getting arrested, if I talk to this country and ask them to lighten up, that’s my approach. It’s not that big a deal to emancipate the Indian person, to free them of colonial chains.”

More than anything, the abstracts embody Yuxweluptun’s “freedom and right to think.” For the anthropologist who might tell him that his is not Native art, he has nothing but disdain: “Is it scary that I may make something that is pleasant? Is it scary me having my own personal freedom to think?” It is not scary at all, and is rather a bit of good fortune for lovers of painting. For all his contrariness and challenge, we should be heartened by his confidence: “I’m a survivor and I will freely emancipate myself as a thinking person and I will walk in my traditional territory and I will talk to this world and some time, at some point, things will change.”

View more works by Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun at canadianart.ca/yuxweluptun