In her apartment in New York City, Kym Greeley would remember Newfoundland through glowing screens. She would repeatedly play one level on Metroid Prime: Phendrana Drifts. Its jagged rocks and snowdrifts reminded her of home.

Longing to paint the landscape she knew, she turned to the Internet for source material, but found very little that reflected her idea of this place. Newfoundland, for her, was not a red-haired child running through a soft field. It was not a brightly coloured home perched on a quiet harbour. For Greeley, her memory of Newfoundland’s landscape was dominated by its monotonous main artery, the Trans-Canada, Route 1, experienced through a car window on the way from one place to another.

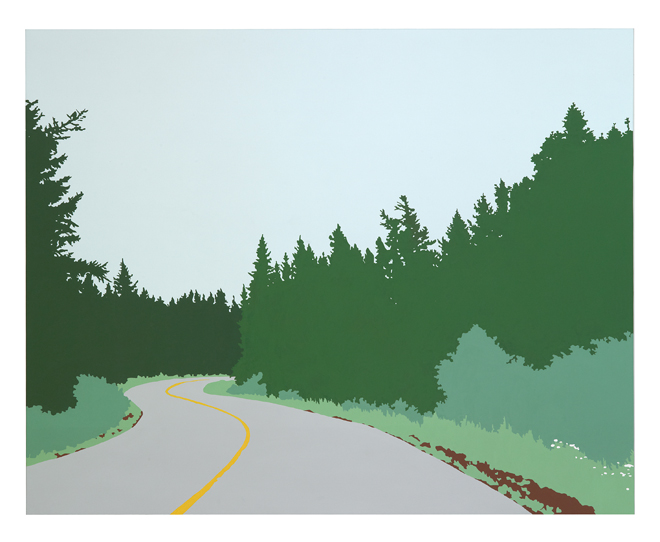

Greeley returned to Newfoundland in 2003. Trained as a conceptual minimalist painter, her windshield became a compositional frame, with echoes of the flat, fixed perspective of video games she played in New York. In her highway paintings, she reduces sentimentality by lessening the emotive hand of the painter through the act of screen-printing. Titles are often abstract, randomly selected. It is Newfoundland, but it could be anywhere, and that is the point.

Kym Greeley, I Feel Alright, 2015. Acrylic with screenprint on canvas mounted on panel, 48 x 72 inches. Photo: Ned Pratt. Courtesy Christina Parker Gallery.

Kym Greeley, I Feel Alright, 2015. Acrylic with screenprint on canvas mounted on panel, 48 x 72 inches. Photo: Ned Pratt. Courtesy Christina Parker Gallery.

Through these works, Greeley has become a significant, if perhaps unintentional, part of something stirring in the arts community on this island. A new generation of artists is eloquently responding to embedded imagery of Newfoundland culture, many doing so after leaving the island for a while. They show a critical reverence for the images that have saturated their understanding of Newfoundland, redefining its cultural landscape through familiar points of reference. This generation should be watched with interest.

Most people know Newfoundland’s roads through Christopher Pratt’s celebrated highway paintings, which document his home province with distanced and distilled respect rather than romanticism. The comparison between Greeley and Pratt is undeniable, but initially unplanned: “I was making the highway paintings and picked up a Christopher Pratt book and I almost fucking barfed. It was almost a direct rip-off. I did not know that work existed. But the comparison is totally valid, if entirely organic. We had these artists in our house. I mean, every time I sat down and did my pee, I looked at a Christopher Pratt.”

Though she was shocked to see such a resemblance, she continued to make her highway paintings after opening that book. Why?

After the birth of twins two years ago, Greeley’s subject matter shifted. The change was predicted by others, and therefore fought: “Even as I was pregnant, people told me my work would change once I had a child. But I didn’t want to start painting babies in the womb, because it’s not how I think about art. I don’t think about it as coming from my body.”

Sitting in one spot with an apparatus that supported two breastfeeding children for 40 minutes at a time, Greeley started drawing the interior of her home. A new series of work resulted that situates the viewer in front of a fireplace mantle, a window largely blocked by a curtain, and stairs seen from the side. Her largely monotonal palette is soft, pulling from the pastel colour schemes found in older Newfoundland homes. These are old colours made new.

Kym Greeley, Just an Illusion, 2016. Acrylic on canvas mounted on panel, 48 x 64 inches. Photo: Gareth Gautier. Courtesy Christina Parker Gallery.

Kym Greeley, Just an Illusion, 2016. Acrylic on canvas mounted on panel, 48 x 64 inches. Photo: Gareth Gautier. Courtesy Christina Parker Gallery.

“I didn’t expect those drawings to become a series, but I realized that I had to acknowledge a change in seeing, that the landscapes I would be doing otherwise would be insincere. They would become commercial, playing to a brand, and wouldn’t reflect my experience.”

Here, the comparison is inevitably to another Newfoundland artist, Mary Pratt, known for her glowing paintings of what surrounds her in her home. If the outdoors is present, it is most often observed through a window.

Greeley’s window provides that same idea of a distant world beyond the home. Yet, rather than Mary Pratt’s charged moment before turning to the next task, Greeley captures time spent in one place. Her claustrophobic staircase, for example, moves beyond the frame, but doesn’t allow you to go any further. This may be Mary Pratt’s realm, in a part of the world where that comparison matters, but Greeley has made it her own.

“All I ever did was just work in the studio,” she says, “even if no one was paying attention to what I was doing. When I came back to Newfoundland for three months, I produced more work than I had in one year—with focus and direction. When I went back to New York, it immediately stopped again. There has to be a right scenario for artists to be productive, and in some cases, isolation is one. I was away long enough to know that. If I didn’t know, I would feel like I need to be a part of the larger arts community. My practice is living here.”

This is a very Newfoundland thing to say.

To understand that, let’s return to the Trans-Canada Highway. It is a road that signifies its own cultural shift, replacing a ruinously expensive and notoriously slow rail system (ironically nicknamed “The Newfie Bullet”). The cost of the railway contributed to Newfoundland joining Canada in 1949. Soon after Confederation, developing government infrastructure promoted the subsistence of artists. Over the next two decades, highly trained, Newfoundland-born artists started choosing to live here. Among them were now-household names such as Christopher Pratt (accompanied by Mary Pratt), Gerald Squires, Rae Perlin, Helen Parsons Shepherd and Reginald Shepherd.

These artists held a pride of isolation, of actively disregarding trends in contemporary art. Stylistically varied, they forged aesthetics that became entrenched in the collective subconscious. They showed the province, and eventually the world, their Newfoundland.

Kym Greeley, Terra Nova 2, 2012. Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 60 inches. Photo: Ned Pratt. Courtesy Christina Parker Gallery.

Kym Greeley, Terra Nova 2, 2012. Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 60 inches. Photo: Ned Pratt. Courtesy Christina Parker Gallery.

Waves of artists continued to arrive as infrastructure further developed. These artists were highly educated and conceptually rigorous, coming here because they recognized a place where they could work—whether born here or not.

And yet, in 1975, art critic Peter Bell wrote: “There has never been anything remotely resembling an art movement in Newfoundland. There have been successive societies and associations of persons interested in painting, but there has been no group with a coherent style or philosophy, nor has there been any developmental succession from one artist to another. Artists in Newfoundland have been, and still are, isolated phenomena. Distinguished, certainly, but independent and unique.”

Although dismissive at first glance, Bell’s description is apt. It may be that Newfoundland’s art history was still too young in 1975 to map any trend. But, more than that, Bell evokes an interesting question, particularly in light of the activities of this new generation: What should an art movement look like?

That question is still a difficult one to answer, but it’s clear that a wave of creative energy is growing. St. John’s has three times the national per-capita average of artists working in other parts of Canada, and Newfoundland and Labradorian artists are exhibited and celebrated internationally. Yet, the work that is created here can often seem asynchronous with the rest of Canada. Why? Zoom into a map of Newfoundland, and you will see a back turned, hard at work. Bell’s descriptors ring true: this place is isolated, it is distinguished, and it is independent.

Kym Greeley, Stairs, 2014. Acrylic on canvas, 4 x 6 feet. Photo: Ned Pratt. Courtesy Christina Parker Gallery.

Kym Greeley, Stairs, 2014. Acrylic on canvas, 4 x 6 feet. Photo: Ned Pratt. Courtesy Christina Parker Gallery.

But are these regional differences, as Bell describes, really what make Newfoundland unique? How are the struggles and successes found here different than anywhere else?

We return to the point of Greeley’s work: This is Newfoundland, but it could be anywhere. Imagery of this place can transcend the local. It is the form of one’s approach to the imagery of that place that matters. The frame of measurement for artistic conversations needs to be telescopic—shifting in and out to encompass this question of difference, recognizing the backdrop of particular histories (and myths).

Greeley has since returned to painting the roads of this island. Why, when the imagery is already so pervasive in the art of Christopher Pratt? She, like many others of her generation, is not crippled by comparison. Greeley represents her sincere experiences of a place, with the onus on the viewer to recognize the difference.

Greeley provides a glance in the rearview mirror. She then fixes the view forward, directing our attention to a landscape where we wonder what might be around the next corner, what will arrive over the rocky hill.

Mireille Eagan is curator of contemporary art at the Rooms in St. John’s.