The Toronto artist Kent Monkman has recently been gaining acclaim for beautifully painted, ornately framed canvases of sublime landscapes that recall early colonial artists such as Cornelius Krieghoff and Paul Kane and the Hudson River School. Set within backdrops of majestic mountains, steep cliffs and expansive valleys are exquisitely detailed, diminutive human figures, dressed in the attire we associate with that period of history. Cowboys, Indians and soldiers appear engaged in the kinds of activities that most of us in North America were taught took place upon contact between the first settlers and Aboriginals. Heroic, fair-skinned Europeans armed with rifles and Christian morals enlighten the Native people in the ways of commerce, fair negotiation and civilized behaviour. These are the stories and histories that Kent Monkman learned at school in Winnipeg. And these are the stories his grandmother and others were taught in residential schools. On closer scrutiny, however, it becomes clear that Monkman’s figures are engaged in encounters of an entirely different sort.

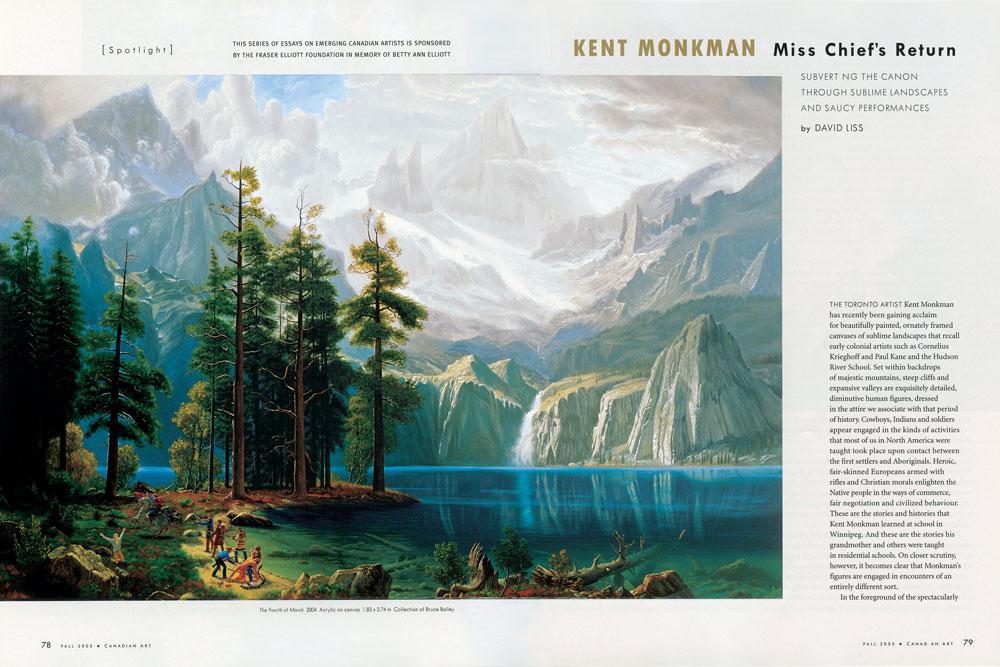

In the foreground of the spectacularly large The Fourth of March (2004), a dramatic scene unfolds on a pathway before a breathtaking lake and mountain vista. Three Metis riflemen are about to open fire on a white man, whose arms are stretched over his head. Two other Metis appear to be holding up a falling Indian in an elaborate chief’s headdress, while Louis Riel rides away on a white horse. What to make of this scene? The Native man with the headdress is clad in pink platform shoes and a slinky pink floor-length loincloth, interrupting any thought that the scene is entirely set in the past. Art historians may recognize that the kneeling, pleading figure and the lineup of riflemen are directly quoted from Goya’s The Third of May (as is the title). Historians will note the date as the day in 1870 when the Metis leader Louis Riel had the Irishman Thomas Scott tried and shot for sedition, an incident that shaped the history of Canada. Further complicating the narrative is that the Scott shooting took place not in an alpine setting, but at Fort Garry in Manitoba’s Red River Colony. Clearly, Monkman is playing fast and loose with his narrative: fact, fiction and our understanding of history are muddied beyond recognition.

A more modestly scaled canvas, Artist and Model (2003), also appears to mess with our assumed notions of history. Again, an idyllic landscape is impeccably painted in a 19th-century style. A Native man similarly attired in headdress, pumps and loincloth stands at an easel painting a white male figure who is tied to a tree, pants at his ankles, and shot through with arrows, like Saint Sebastian. Another picture, The Rape of Daniel Boone Junior (2002), suggests, well, pretty much what the title implies, with male Aboriginals subjugating a white man. Indeed, Monkman’s paintings will not be mistaken for long-lost Krieghoffs.

Standing in the artist’s homey studio in Toronto’s Dupont and Christie neighbourhood, surrounded by paintings, I feel suspended among history, modernity and the drama of our times. I am familiar with 19th-century painting—it is imprinted as part of our collective consciousness—but I cannot claim to possess an encyclopedic knowledge of it. But Kent Monkman does. Articulate and passionate about his subject, he rifles through his extensive library, fielding inquiries and filling in the gaps in my knowledge by presenting pictorial references that have informed his reading of history and his work. Monkman knows the canon well enough to be able to read between, around and through the narratives that we have come to accept as our heritage. The stereotypes, the racism, the violence and the power struggles that the New World was founded upon (and that are perpetuated to this day) are of course fertile ground for a contemporary artist of Cree ancestry.

Monkman, a Swampy Cree of mixed English and Irish descent, grew up in Winnipeg and, while young, lived on various northern reserves as his father travelled about the area preaching Christianity to the Cree in their own language. As a result, his contact with the Cree language was filtered through Christianity in the form of hymns. He started out in Toronto as a set designer for theatre and dance, and was an accomplished illustrator. More recently, Monkman has created installation, performances and interventions, and he has produced film and video since 1996.

His breakthrough as a visual artist was an extensive series of works titled The Prayer Language. Inspired by Foucault’s notion of sexuality as an exchange of power, he sought to explore his ancestral language as a physical construct and the body as a site of contention, inflected by conquest, struggle and implicit questions of identity. The paintings are fabricated in ways that mimic the layers of the body, of language and of history. Monkman paints Cree syllabics as employed in Christian hymns in semi-transparent acrylic. Below these layers are organic forms that in some cases resemble human anatomy and in others are slightly more recognizable as human figures, entwined ambiguously in ecstasy or struggle. Cree language expressing European Christianity and the physical power relations inherent in the human condition are all articulated through the vocabulary of contemporary Western painting.

Monkman has assimilated the skills as well as the diverse discourses of our heritage and times. He is fascinated by their legacy and by how our perceptions and understandings of the world have been shaped and even dictated by the dramas, stories and language of the past. Of particular interest to him is how the European Christian viewpoint came to supplant and dominate the cultures indigenous to North America. Monkman studied the pictures that told the stories of that domination: the paintings of Kane, George Catlin, the Hudson River School and Krieghoff. While these artists ostensibly recorded and captured scenes from the New World for understanding and posterity, we have over time come to see the artistic licence in their work: to a degree, images and stories were fabricated to conform to their own expectations and values. Painting was, at the time, a crucial accompaniment to the project of convincing Native people of the supposed savagery of their ways. Indeed, even the ability of the white colonists to render landscapes and figures so articulately in pigment was evidence of their superior sophistication and the powers they possessed.

A detail not lost on Monkman was George Catlin’s fondness for occasionally inserting himself into his pictures as a handsome and heroic central player. In response, Monkman created his own persona. Miss Chief Share Eagle Testickle is the flamboyant, high-heeled alter ego who appears in his paintings and performances. Modelling this figure after colonial myth, Hollywood cliché and, very specifically, the costumes worn by the pop singer Cher at the time of her huge 1973 hit Half-Breed, Monkman plays with the offensive, or at least cheesy, stereotypes found within the dominant culture as he deconstructs and subverts them. He is determined to have some fun with the process, suggesting that history, as it pertains in any case to constructed notions of Aboriginal identity, is a largely subjective and arbitrary fabrication, no more valid or trustworthy than fiction. Liberated from the constraints of accepted dogma and with a flair for the dramatic, Monkman feels perfectly free and justified in playing out his own fantasies across the theatre of history. As inventive and subversive with history as he is talented with a paintbrush, Monkman is equally dexterous with language, as a careful reading of his alias reveals: Mischief Cher Egotistical.

The theatricality underlying Monkman’s practice is not surprising, given his history in set and costume design for Native Earth Performing Arts in Toronto. As a young adult, he was drawn to the theatre, where, he noticed, “They had Native actors onstage, they had Native writers and Native directors, but there wasn’t yet anyone from the Native community who was designing for the stage.” He has an impressive number of credits in the field, including sets and costumes for Diva Ojibway by Tina Mason, Lady of Silences by Floyd Favel and dance pieces at the Canada Dance Festival in Ottawa, including Child of 10,000 Years and Night Traveller by Michael Greyeyes and Floyd Favel.

At just shy of his 40th birthday, Monkman has an impressive record over the past half-dozen years. He has been included in important group exhibitions at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal and Museum London, and his works are in the collections of the National Gallery of Canada, Woodland Cultural Centre in Brantford, Robert McLaughlin Gallery and significant private collections. His short films and videos have been screened at such prestigious showcases as the Sundance Film Festival.

Performance is another form of expression that seems natural for Monkman. At the opening reception for a recent exhibition of his work at Toronto’s ultra-hip Drake Hotel, Monkman donned a series of four costumes and made dramatic entrances into the lounge area of the bar. These were Miss Chief’s various personas: Cher’s Bob Mackie-designed glam look; Mrs. Custer, from Monkman’s recent remake of William S. Jewett’s painting The Promised Land—The Grayson Family (1850); Miss Tippy Canoe, a trapper’s bride in fur bikini and a bugscreen mesh number created by fellow artists Bonnie Devine and Paul Gardner; and the Warrior Princess, decked out in “Oka-chic” to entertain the troops behind the barricades. The costumes were displayed in the hotel lobby along with several paintings for the duration of the exhibition.

The performance and installation were modelled after a travelling exhibition that Catlin staged in the 1840s. He toured Europe with his paintings, costumes and tableau vivant of actors and Iowa and Ojibwey Indians, who would enact “typical” New World scenes and dances, conceived by Caitlin and presented to audiences as authentic Native experience. As absurd and mocking as Monkman’s characterizations may be, he is Cree after all, and his interpretation of Native culture and behaviour is certainly as valid as any white man’s, if not more so. The stories are all in the telling, and, perhaps more importantly, in the gaps in language and interpretation.

Last June, Monkman was invited to bring Miss Chief Share Eagle Testickle’s Travelling Gallery and European Male Emporium to Compton Verney, a museum in Warwickshire, England, for a performance in a group show co-curated by Richard William Hill, formerly a curator at the Art Gallery of Ontario. In this project, colonial roles and gender expectations are reversed, as white men (actors hired by the artist) become the subjects of ethnological study by the cross-gendered Monkman/Miss Chief, who arrives at the doors of the museum splendidly decked out in drag and on horseback. This is part of a series of performances Monkman calls Colonial Art Space Interventions, the most notorious of which took place at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario, in August, 2004, and was amusingly titled Group of Seven Inches.

As the premier home of the art of the Group of Seven, the McMichael is significant in the accepted canon of what constitutes Canadian identity, or at least one version that is readily identifiable. As an institutional gatekeeper, the McMichael exercises a certain power over what is included and what is not. The Group’s romanticized depiction of the Canadian landscape as an unpopulated, undiscovered wilderness is not lost on Monkman, who regards history as a mythology forged from relationships of power and subjugation. In a series of watercolours from 2001, Monkman painted landscapes directly quoted from well-known paintings by the Group of Seven. In the foreground of each is a cowboy on all fours being mounted from behind by an Indian. The ambiguous embrace implies both a struggle and a sexual act, though cheeky titles such as Big Wood and Prick Island suggest the latter. In Superior, Monkman lifts his composition from Lawren Harris’s famous North Shore, Lake Superior (1926). The couple are doing their thing at the base of a tree trunk, turning the majestic icon from a symbol of nature’s regenerative cycles into a hilariously blatant phallic symbol. Developed from the immediately preceding Prayer Language paintings, these works are also densely overlaid with text, in English this time—racist and violent passages from pulp westerns and gay porn stories from the Internet that fetishize Aboriginal men. For Monkman this combination takes aim at the Group of Seven’s colonialist chauvinism and its by-now notorious exclusion of women from the tight-knit circle. The layering of image and text is literally reflective of the complex layering of power, eroticism, morality and xenophobia at the root of our Canadian identity. Despite the scathing critique embodied in the watercolours, the McMichael gamely played along and installed five of them in their members’ lounge during Monkman’s performance intervention.

Taking these notions further, Monkman developed his current and best-known work, the series of paintings he refers to interchangeably as The Moral Landscape or Eros and Empire. The foundation of this series is three large works that form The Trilogy of St. Thomas: the aforementioned The Fourth of March, Not the End of the Trail and The Impending Storm (all 2004). The works tell a mythological tragic gay love story, conceived as a metaphor for the entwined histories of and relationships between white settlers and Native people. By adapting the painterly conventions of romantic 19th-century landscape and by (con)fusing fact and fiction, Monkman is liberated to project his own stories upon the landscapes that were the sites of contact and contention.

Eros and Empire extends Monkman’s investigation of the connection between morality and conquest in colonization and the effects of European religious traditions on Native cultures. Since first contact, the repression of sexuality has played a seminal role in the colonization of Aboriginal people. It was reinforced by government and church-sanctioned residential systems that fought aggressively to obliterate Aboriginal identity and advocated the adoption of Judeo-Christian attitudes towards sexuality and morality. Through the invention of his own entertaining allegories—mischievously rich in the blending of fact and fiction, role reversals, gender- and genre-bending, ironic stereotypes, humour, horror and challenges to the accepted canon—Monkman reinvigorates our engagement with difficult questions about who we all are and how we got here. He reminds us that documented history is subjective and that large and significant amounts of it remain untold, unspoken and obliterated.

It is doubtful that Kent Monkman believes any of his cajoling will change the dominant reading of history. However, he makes us aware of the damaging effects of marginalization and oppression, and of the multiplicity of stories and truths that need to be acknowledged and included in the dialogue. There is a hopeful aspect to the work. In the lower left corner of The Impending Storm, Miss Chief Share Eagle Testickle and a white man with blond hair have just disembarked from a canoe. Fleeing the ominous storm clouds that threaten the journey, they are running off, away from the central narrative, arm in arm, together.

This is a feature from the Fall 2005 issue of Canadian Art.

Spread from the Fall 2005 issue of Canadian Art

Spread from the Fall 2005 issue of Canadian Art