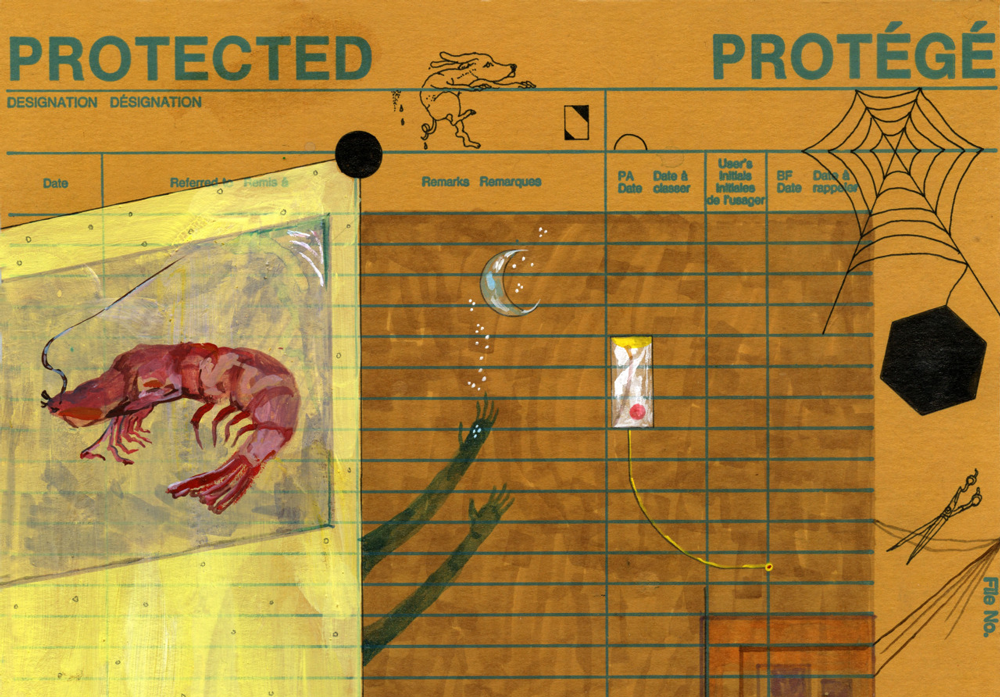

Kendra Yee, 1/20/2014, 3:47 pm. Drawing on envelope.

Kendra Yee, 1/20/2014, 3:47 pm. Drawing on envelope.

“The art of letter-writing has only just come into existence.”—Virginia Woolf in “A Letter to a Young Poet”

“I want each letter to only be its own copy,” writer and poet Tova Benjamin remembers telling illustrator, sculptor and artist Kendra Yee a year ago, prior to preparing for their current exhibition of writing and mixed-media artifacts, “To Whom It May Concern,” at Toronto’s Xpace Cultural Centre. Benjamin holds a kinship to the epistolary format when she talks about the letters that she wrote to her loved ones, to strangers, to herself, in no particular order, from 2013 to 2016.

“When I’m far from someone, the best way to feel close is to write to them,” Benjamin continues. Addressed to a specific individual, the letter is inaccessible to a stranger. Even as it entices the public reader, its revelations withhold, and obscure entry.

Part of Tova Benjamin’s installation at Xpace. Photo: Sarah Bodri.

Part of Tova Benjamin’s installation at Xpace. Photo: Sarah Bodri.

In the exhibition, Benjamin’s diary entries and letters are placed in office files, marked by year. These files are kept on a table in the middle of the gallery. Next to the table is an overhead projector, the kind used in classrooms, onto which viewers place the letters (copied onto sheets of transparent plastic) and thus see them magnified as projections on the wall.

These letters, unedited—in Woolf’s terms, “intimate, irreticent, indiscreet in the extreme”—are taken from Benjamin’s personal collections. Illuminated with enlarged font on the wall, they read like memoir, documenting instances of calm, trauma, pleasure, ache, longing, familial affection and alienation.

“I’m craving that there-ness intimacy right now,” Benjamin writes pleadingly in one of her letters. “I don’t know if I will send this letter to you, it feels drippy and unnecessary,” another confesses. The one written on April 25, 2016, reads: “I’ve had a letter stewing somewhere in the back of my head or maybe around my lungs ever since Sunday night.”

Kendra Yee and Tova Benjamin, “To Whom It May Concern” (installation view), 2017. Photo: Sarah Bodri.

Kendra Yee and Tova Benjamin, “To Whom It May Concern” (installation view), 2017. Photo: Sarah Bodri.

Benjamin’s ruminations are also frozen and captured in the gallery as visuals in illustrations, drawings, ceramic- and bronze-based miniatures and hanging sculptures created by Kendra Yee. Yee has carefully sited each of her works in distinct locations in the room. A bronze snail sculpture sits on a shelf, a sack of rice hangs from a chain on the wall. In one ceramic hanging, a plump drop of blood dangles by a thin metal chain from a pale fingertip on a hand above it. It recalls one of Benjamin’s letters, where she writes, “Sometimes we want to drip on the people we love.”

In all her letters, Benjamin makes sure to strike out any names or identifying details of either the recipients or subjects of discussion with a black Sharpie. So you see letters like blotched and smeared documents in an aging archive—the previous handlers’ fingerprints blurring the once stately dark font—projected on the wall as objects of almost scientific inquiry.

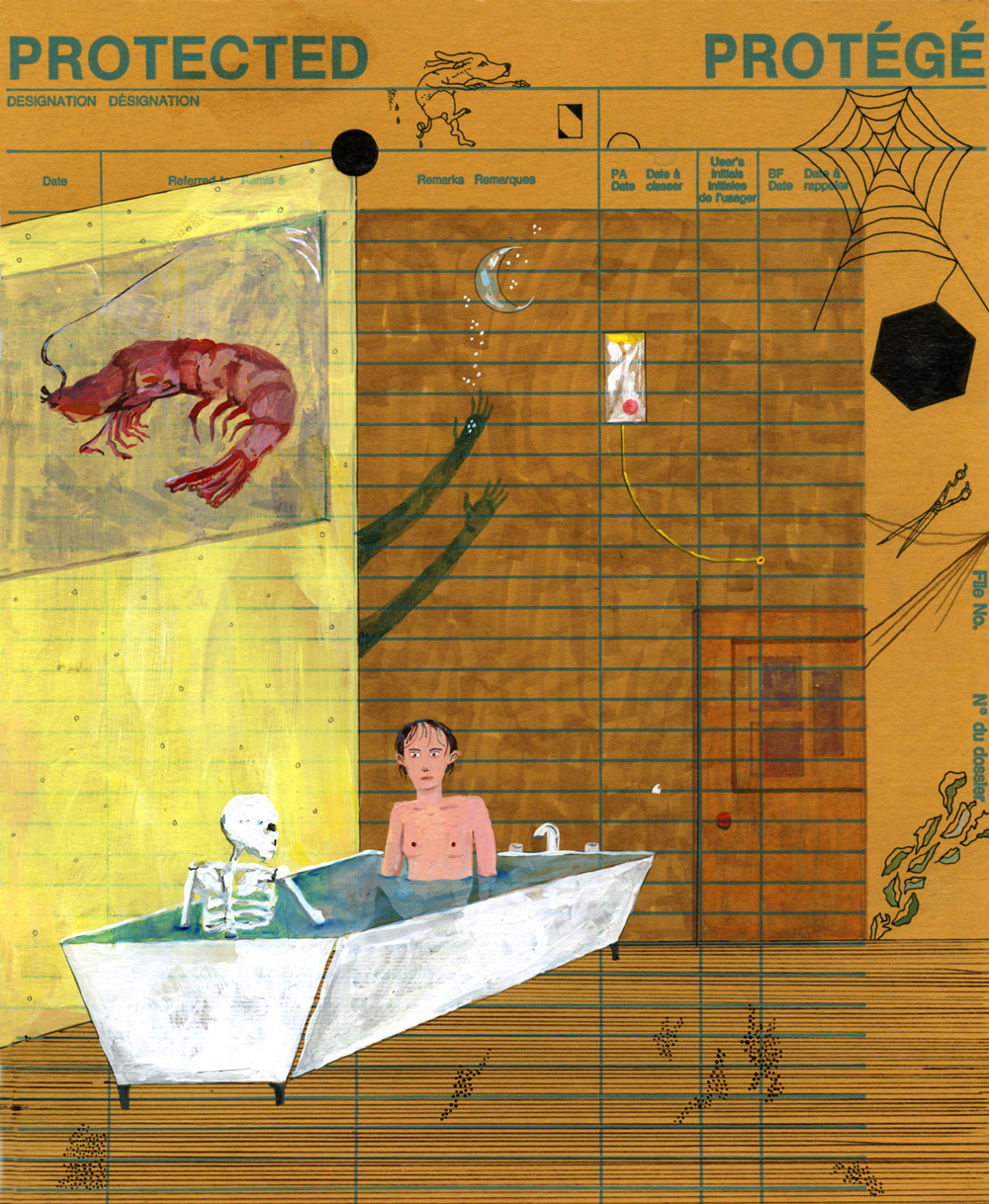

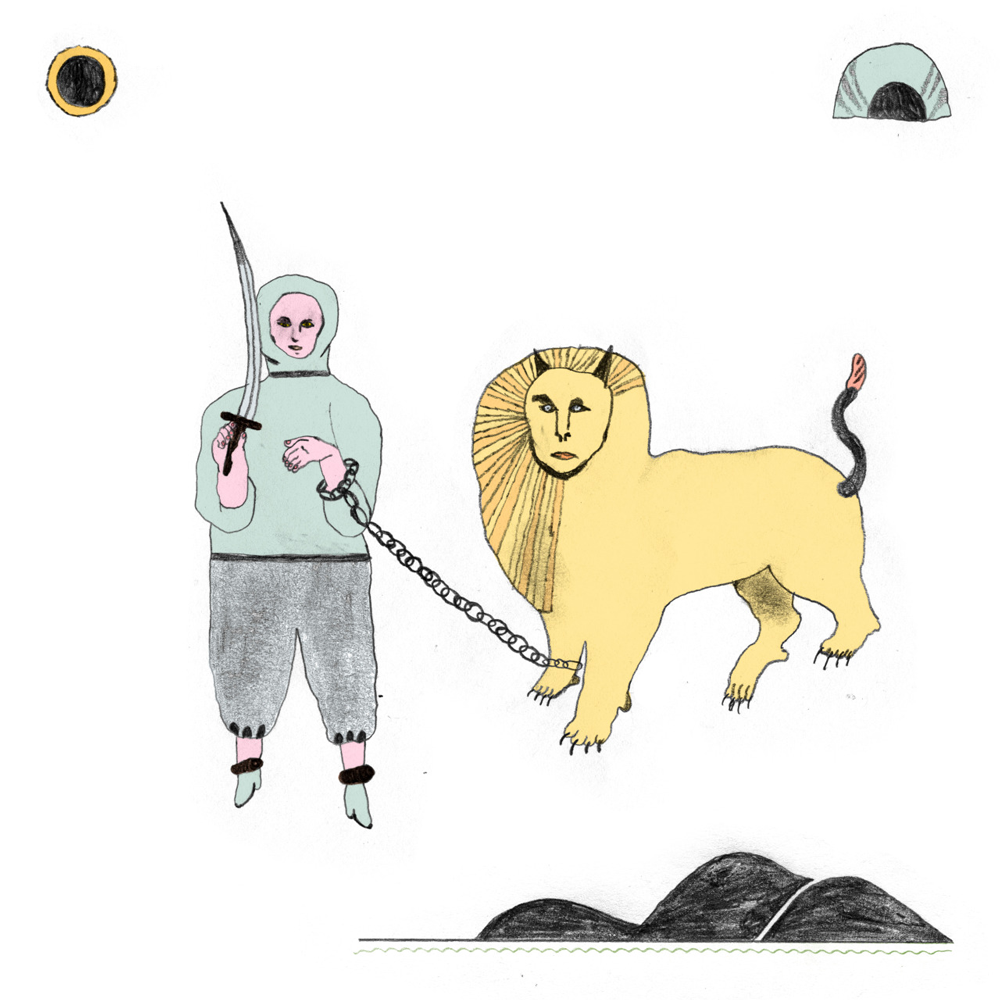

Yee’s sculptures and drawings affirm this sense of anonymity; her works contain figures that have no distinct facial markings, the features on her portraits are obscure, twisted and sometimes so nondescript they look like ghosts.

This mystery feels appropriate, since the sense of the sacred that Yee and Benjamin’s marriage of text and image aspires to is fraught with moments of conjuring, faith, as well as the lack of both.

Kendra Yee, 5/11/14, 11:03 pm. Digital print on fabric.

Kendra Yee, 5/11/14, 11:03 pm. Digital print on fabric.

“We both love exploring personal myths, as well as the idea of coming from different cultures, and what kinds of expectations there are of us,” Yee explains, referring to the wall across from the one where Benjamin’s letters are projected. “This is the ‘religion’ wall,” she says, pointing to the ceramic figure of a ghost with an image of Menachem Mendel Schneerson—the influential, late religious leader of Chabad-Lubavitch, the Hasidic community Benjamin was raised in—painted on its chest. Below the ghost are faces printed on a strip of paper, black and white illustrations of unidentifiable, indistinguishable crowds, their features grim and comically bare. These represent bodies in faith—some indifferent, some in mourning of Schneerson, who died in 1994, the year Benjamin was born.

“He was the beginning to what my relationship with images is,” Benjamin recalls of Schneerson, adding that, while growing up, she was taught, “whenever his image would fall on the floor, you were supposed to kiss it.” The first sculpture or image we often see is one we are meant to look up at: a deceased grandparent, a spiritual being, a sacred script framed on the wall. It’s also the first image, then, that instills shame in us should we accidentally mistreat or drop it. There is a humbleness the body performs by looking down, bending, kneeling.

Yee realizes this gesture, a stance that seeks forgiveness but also solace, in a bronze sculpture of an angel, kneeling on a shelf, under the figure of the ghost, as though in quiet service.

“You’re supposed to be the angel,” Yee tells Benjamin playfully, only to reveal to me later in our conversation the formative role of angel imagery in her life. Being raised by a Catholic grandmother herself, as a little kid, her “favourite nighttime prayers were the ones with the angels.” She shyly adds that although she’s not religious, “sometimes, when I’m still nervous, I’ll pray to angels.”

The ties that bind us to a hymn or verse from sacred script feel often most pronounced in moments of crisis or strife. Faith is the defense mechanism many children are raised with, and it is in bodily ritual that the show of devotion is acutely learned.

Kendra Yee and Tova Benjamin, “To Whom It May Concern” (installation view), 2017. Photo: Sarah Bodri.

Kendra Yee and Tova Benjamin, “To Whom It May Concern” (installation view), 2017. Photo: Sarah Bodri.

One of the most memorable parts of the installation dedicated to faith is a pair of pink Crocs with a worn, American one-dollar bill peeking out; it’s positioned on the ground below the ghost of the Rebbe. “Crocs were the thing at one point, in like 2005,” Benjamin is fighting tears of laughter as she says this, adding that for her they are “also the shoes you put on during Yom Kippur,” the Day of Atonement being the most important holiday in Jewish faith, and one where leather-soled shoes are not allowed. It’s customary for people—across cultures, she notes—to remove everyday footwear before entering a sacred site. Before approaching Rebbe Schneerson’s grave or “ohel” (which roughly translates to “tent”) visitors are required to do the same. Benjamin tells me that this installation, for her, “is really a throwback,” as she is reminded of the odd but familiar stacks of Crocs near that ohel, ready to be worn.

Part of Kendra Yee’s installation at Xpace. Photo: Sarah Bodri.

Part of Kendra Yee’s installation at Xpace. Photo: Sarah Bodri.

The twinned closeness and distance we cultivate, fracture and negotiate with ritual, with familial piety, also imbues many of Yee’s artifacts, perched atop shelves on each of the walls. Yee derives her style from a variety of techniques, of which sketchbooking, the hallmark of zine culture, feels most intimate. As I scan the room filled with what feel like minute treasures in a museum, her works seem to surround Benjamin’s projection of letters like bubbles in a fair; they twinkle in constellation, miniscule, dispersed, suspended. Celestial forms are one of many muses of the artist, as seen in her drawings of stars, collage-like prints collating wrinkled faces with moons, geometrical shapes with floating cars. There are earthly elements, too, weighing creatures down or sometimes offering them respite or shelter.

One of the works, a bronze sculpture of a spider placed on top of a shelf, is linked by about a metre of a metal chain to a large bronze spider web hanging from a wall. In a smaller bronze work, a man is chained to an olive tree. “I think it’s the idea of hanging on, wanting to hang on to something, grasping to figures, or places, or mentors or ideas and really wanting to hold on to it,” Yee says. While chains render the heft of being tied down to a traumatic memory or image, they also, as Yee notes, “swing you, carry you to places where you eventually want to be.”

With both Yee and Benjamin having already contributed together as an artist-writer duo for online comics in Rookie magazine, I wondered how Yee managed to create works that are required to speak foremost to Benjamin’s writing, and then to her individual context. How much of herself did she see in these letters that she had to visually render?

Part of Kendra Yee’s installation at Xpace. Photo: Sarah Bodri.

Part of Kendra Yee’s installation at Xpace. Photo: Sarah Bodri.

“I let Tova’s writing guide me, I try to let the medium emerge from that,” she tells me. She also confesses, “I hate reading,” but Tova’s writing “mystifies her.” “When a word feels just comfortable in a sentence, that’s what her writing is like.” Yee appears endeared, leaving Benjamin to laugh and blush.

Writer Joanna Biggs writes in her review of Elena Ferrante’s The Story of the Lost Child, that for her, in reading Ferrante’s female protagonists, ““She’ irresistibly becomes ‘I,’ a confessional ‘I.’” In a somewhat archaeological feat to illuminate personal histories, both Yee and Benjamin have found ways to become one another.

Prior to their most recent collaboration in this exhibition, Benjamin wrote Yee a letter saying that she was unsure about the direction their project would take, but that “it will be fine,” and that they would figure out how to make it work. This, laughably, did not have the desired effect; Yee “freaked out,” and texted Benjamin back saying, “Dude, your letter!” Later, in person, Yee told Benjamin, “It scared me.” While narrating their individual versions of this incident to me, both of them burst into laughter.

Yee and Benjamin have a playful but curious take on each other, a trained energy that only collaboration between two friends can foster. It is what correspondence between lovers, sisters and companions is grounded in. In this bond reside secrets, a desire to keep information safe from audiences—but also the will to allow each other a comfort to be more vulnerable, more embroiled in each other’s practices.

When incarnated into tangible form, the letter becomes artifact (and artifact becomes language). A museum of a life lived—of found objects, trimmed dolls, blacked-out words, untitled images, forgotten moons, selected horoscopes—germinates. It turns out the written word, stamped, enveloped, sealed, is always witness to at least one person. And that may just be enough.

Aaditya Aggarwal is the online editorial intern at Canadian Art. “To Whom It May Concern” by Tova Benjamin and Kendra Yee is on view at Xpace Cultural Centre until March 24, 2017.