In 1972, American postmodern writer Kathy Acker self-published a chapbook entitled Politics, a blunt, jumpy account of the brief time she spent performing in a 42nd Street sex show. It was stylistically different from Acker’s later work—more free verse than prose, for one thing—but its obsessive, hyberbolic anatomization of sex and power established the subject that would define her entire oeuvre. For Acker, sex and power were as inextricable as writing and reading, sex and writing, writing and politics. She famously wrote while masturbating, appeared in a handful of porn loops, and her subsequent, cutting-edge novels—including Blood and Guts in High School and Empire of the Senseless, to name two of the best-known—all hinge, in various complicated ways, on the treachery of love.

Acker’s work borrows tropes and strategies from pornography, but it wasn’t until years after Politics—and the Black Tarantula trilogy that cemented her reputation in the downtown New York art world—that Acker deliberately tried to write an actual porn novel. Poets like Diane DiPrima had written such books for a fly-by-night company called Venice Books, getting paid $800 a shot. To Acker, perpetually broke until she inherited money in 1980, it seemed like an easy way to make a fast buck. And also a kind of formal challenge—she’d long experimented with different literary constraints, and here set out to “mathematically compose” a book: every other chapter would be a porn chapter; each chapter, except for the central one, would mirror the facing chapter. Story and character were of little interest to her, but she found it interesting to simulate a plot and to create characters devoid of conventional psychology. As she wrote later, “I wanted to stick a knife, a little one, up the ass of the novel.”

Illustrations by Robert Kushner in Kathy Goes to Haiti, published by Rumour in 1978. Courtesy Judith Doyle.

Illustrations by Robert Kushner in Kathy Goes to Haiti, published by Rumour in 1978. Courtesy Judith Doyle.

That little knife was Kathy Goes to Haiti. On a grant, in 1977, Acker spent a couple of months in Port-au-Prince, the Haitian capital—it was her first time outside of North America—and she came back both fascinated and shaken. “It was in the middle of the Baby Doc shit,” remembers her cousin, dancer and choreographer Pooh Kaye, “and she was being hassled continually. She said guys were knocking on her door every night.” Acker transformed this menace into a narrative of libidinal, colonial and ontological desperation. With its intentionally naive, discordant language and bursts of graphic sex, it feels, at times, like Anaïs Nin doing her best Jane Bowles impersonation.

Around the time Acker finished writing the book, in 1978, a scrappy new publishing house–cum–art gallery called Rumour Publications was setting up shop in Toronto. The brainchild of three York University students, Judith Doyle, Fred Gaysek and Kim Todd, Rumour was a storefront space at 720 Queen Street West (now the home of the original Terroni restaurant), then a largely Polish and Ukrainian working-class neighbourhood. The space was formerly a jewellery store and still had its wooden shelving; Rumour used these to display the chapbooks they started making—prefiguring the nascent zine culture—on a leased Xerox photocopier. (Gaysek subsidized Rumour with a number of day jobs, including one at a copy shop, where he also ran off books.) Doyle and Todd (who would soon abandon the venture) lived in the two-bedroom apartment upstairs; the three of them rented the entire building for $400 a month.

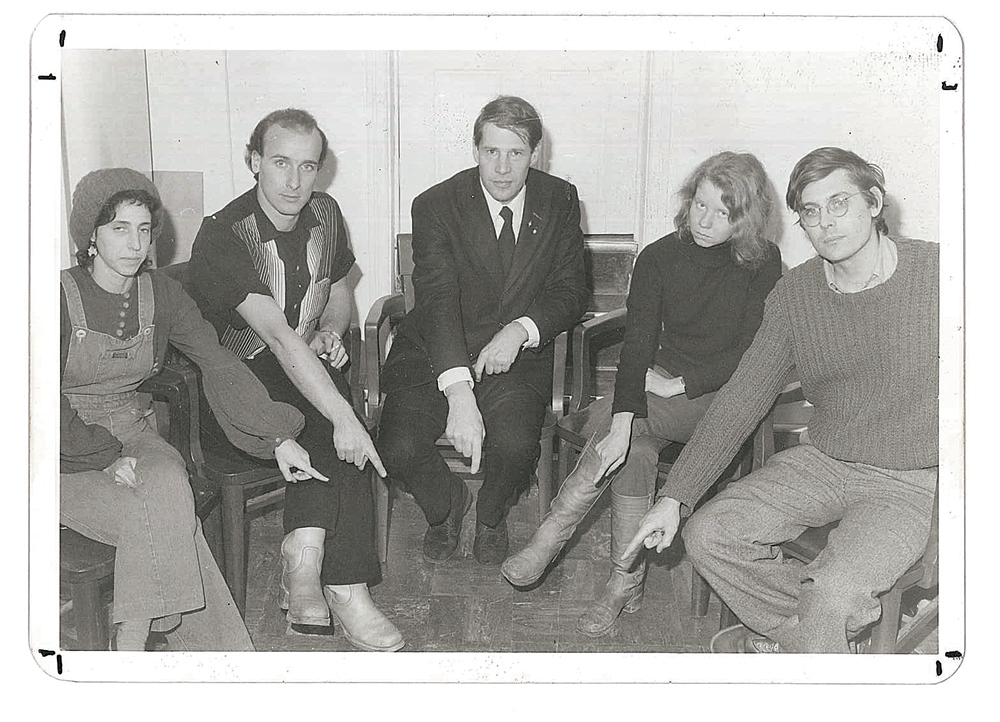

Worldpool founders (from left) Sharon Lovett, Fred Gaysek, Willoughby Sharp, Judith Doyle and Norman White at Rumour in Toronto 1978. Courtesy Judith Doyle. Photo: Victor Coleman.

Worldpool founders (from left) Sharon Lovett, Fred Gaysek, Willoughby Sharp, Judith Doyle and Norman White at Rumour in Toronto 1978. Courtesy Judith Doyle. Photo: Victor Coleman.

Doyle and Gaysek, lovers at the time, wrote poetry—Doyle in the back, Gaysek typing at a large desk in the centre of the main room—and they published books by Philip Monk, then an emerging art critic, painter Brian Kipping, and, of course, themselves. They were also interested in newer, hybrid, less traditional forms. With musician John Kuipers on Buchla synth, they formed an improvisational performance ensemble called Test Patterns. And after Doyle began an affair with Willoughby Sharp, the New York art world impresario, she and Sharp co-founded Worldpool in the Rumour back room—an “artist-run telecommunications/teleculture global network” that met once a week to produce and exchange fax and proto-Internet art with a host of international correspondents.

Rumour was a bit player in the evolving, competitive, fractious Toronto art scene, but it was allied with A Space, the interdisciplinary gallery and performance space on St. Nicholas Street that billed itself as the country’s first artist-run centre. Throughout the ’70s, A Space had been a hotbed of experimental work, hosting solo shows for the likes of Ian Carr-Harris and General Idea, and it was one of the first Canadian galleries to embrace video art. In 1974, poet and former Coach House Press editor Victor Coleman, who had also taught Doyle at York, became the director at the gallery (out of which he also published the influential art-and-literary magazine Only Paper Today). Coleman was tight with Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs—two writers close to Acker’s heart—and he’d also been among the hundreds of literary and art-world figures to whom Acker, when she first started serializing her Black Tarantula books as mail art, sent her books. He was deeply impressed with what she was doing: “She was a ballsy writer, taking chances that nobody had ever thought of.”

Coleman had heard about Kathy Goes to Haiti. More specifically, he’d heard that the book’s publisher had gone bankrupt and the book, by now copy-edited and designed, was homeless. Coleman suggested Rumour publish it and both they and Acker jumped at the chance. Rumour ended up printing somewhere around 1,000 copies—no one remembers how many exactly—and paid for it out of the proceeds Doyle and Gaysek received for writing the novelization of a horror movie called Something’s Rotten. American decorative artist Robert Kushner provided appropriately racy illustrations.

Illustrations by Robert Kushner in Kathy Goes to Haiti, published by Rumour in 1978.

Illustrations by Robert Kushner in Kathy Goes to Haiti, published by Rumour in 1978.

The relationship made sense in many ways. While Acker had spent her early 20s haunting the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery— the unofficial clubhouse for poets like Bernadette Mayer, Ted Berrigan and Eileen Myles—her aesthetic ambitions were shaped even more distinctly by the visual art world. Her early mentors and lovers included renowned film scholar P. Adams Sitney (who introduced her to Jack Smith and Carolee Schneemann, among others), and Conceptual artists Dan Graham and David and Eleanor Antin. As in Toronto, the downtown art scene that Acker became a part of in mid- to late-’70s New York was collaborative, multidisciplinary and, to use an anachronistic term, platform-agnostic—musicians made films, painters wrote poetry, academics produced parties. And though Acker identified as a writer and published books, her writing was really written to be performed—what could be monotonous or confusing on the page became funny, bracing, even sublime when she read it out loud. Acker’s reading style—intimate, incantatory, vaguely sinister—became notorious. She was the first fiction writer to appear at the experimental performance space the Kitchen.

Acker came up to Toronto in late February 1979 to participate in several events put on by Rumour. Doyle was initially intimidated—while Acker had only really begun publishing, she was already an art-world star and fiercely opinionated. “She would lose patience with even the slightest bit of stupidity,” Doyle says. The two nonetheless quickly became friends. Acker stayed in Doyle’s apartment above Rumour and they often hung out on the back patio at Tiger’s Coconut Grove, a Jamaican dive in Kensington Market. Gaysek warmed to her immediately. They played chess in the kitchen of the Shaw Street Victorian he rented, talked about Zola. “She was a very honest person,” Gaysek says. “And she wasn’t going to be pushed around by anybody.”

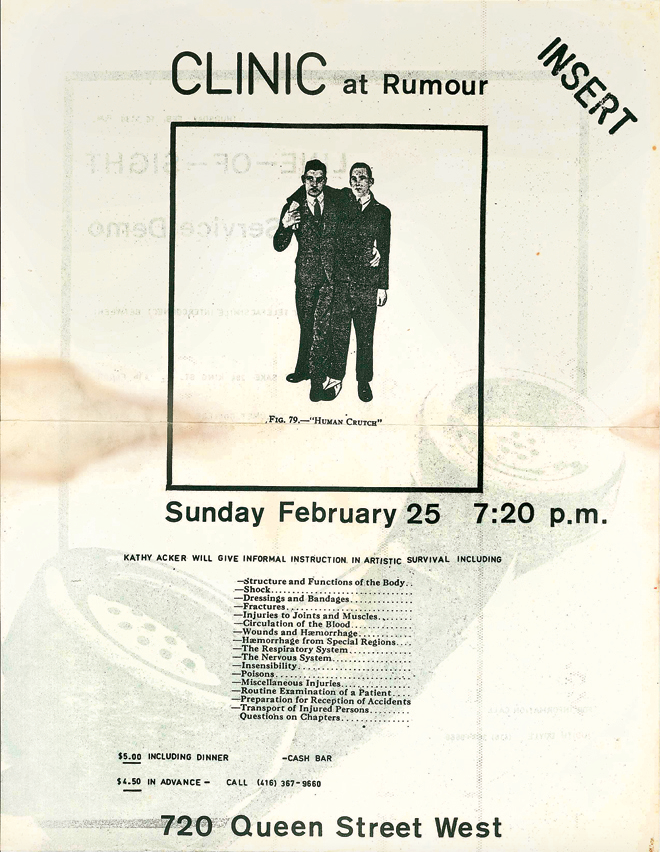

Poster for Kathy Acker’s writing workshop on “artistic survival” at Rumour in Toronto, 1979. Courtesy Judith Doyle.

Poster for Kathy Acker’s writing workshop on “artistic survival” at Rumour in Toronto, 1979. Courtesy Judith Doyle.

At Rumour, Acker taught a writing workshop, or what Doyle referred to as a “clinic.” The flyer borrowed its central image from a medical textbook: a photo of two men in suits, one with a bandaged foot, the other propping him up, with the caption “Human crutch.” It promised that Acker would give “informal instruction in artistic survival,” and cover such topics as “Structure and Functions of the Body,” “Shock,” and “Insensibility.” The event cost $5, with dinner—made by Doyle and Gaysek—included. About 10 people showed up, including 18-year-old John Greyson, who had his first public art exhibition in the Rumour window (an installation featuring text and 50 red mittens that Greyson had sewn himself). Doyle remembers Acker mostly workshopping her own writing, testing it out, but Greyson recalls her also instilling in them a certain discipline: “The main thing I remember is her saying that you have to write every day. Assign yourself a number of hours or words a day. It hurts, it’s like jogging, but eventually it becomes addictive, a habit, and that’s when it kicks in. No matter how much you doubt, you have that three hours a day or 1,000 words, whichever comes first, you have that as your anchor, and it becomes your studio practice.”

Acker, then 31, wasn’t the tattooed, pierced, bodybuilding style maven that she famously became, but a more physically unassuming gamine with a fondness for short skirts, tights and oversized cable-knit sweaters. “I thought she was actually kind of frumpy,” Gaysek says. Others, however, found her far more attractive. Andy Paterson, an artist, writer and front man for Toronto art-punk band the Government, met Acker at a February 23 reading she gave at 466 Bathurst Street, a performance-and-art space— and early progenitor of CineCycle—run by Chrysanne Stathacos and Martin Heath. There, Acker read from “The Scorpions,” a story she would later fold into Blood and Guts in High School, and had Doyle play certain characters or parts. “We knew we couldn’t change the shit we were living in,” Acker wrote, “so we were trying to change ourselves.”

The acerbic, eccentric Paterson, who was 26 at the time, was fascinated— by her work, her status, her punkish pixie appearance. (It helped that they were about the same height.) At any after-party on Queen Street West, they hooked up. “I thought she was utterly unique,” Paterson says. “For a couple of weeks, we kind of hung out all the time.” The chemistry was both physical and cerebral—they saw movies (Acker loathed the New German Cinema, loved The Warriors), talked about books (Beckett bored her, she adored Austen) and, of course, had sex. “Kathy once told me I could talk like a writer,” Paterson remembers, “but I could fuck like a musician. Which means, probably, a bit brutal.” There were dinners with other writers—David Young, Sarah Sheard, Coleman—and, towards the end of Acker’s visit, she and Paterson performed together at 466 Bathurst Street, with Acker reading about her mother’s recent suicide. “It wasn’t entertainment,” Paterson says.

But Acker’s romances were almost always rocky and her relationship with Paterson was no different. “Kathy liked to talk about being in love,” Doyle says. “She loved to be completely, totally infatuated. If it was Andy, it was all ‘Andy, Andy, Andy.’ But Kathy Goes to Haiti is a good model. They would be like relationships you have when you’re travelling or on a summer vacation. There would be this kind of intensity and then it would end.” They argued frequently—about glam rock or Paterson’s anal retentiveness. Paterson once told her that if she wanted to be taken seriously as a writer she should stop calling herself Kathy.

After Acker left Toronto in March, the relationship limped along through the spring and summer. Paterson borrowed money so he could visit her in New York. At the end of the summer, she returned to Canada—Paterson was now roommates with Gaysek on Shaw Street—and after a couple of good days, things turned sour again. “Kathy became bored with me,” Paterson says. “I was boring. I talked too much about rock ’n’ roll.” And then, like so many people in Acker’s life, Paterson was transformed, more or less, into a character. In one of her chapbooks, Algeria: A Series of Invocations Because Nothing Else Works, Paterson is named Kader and Acker’s narrator is both obsessed with and repelled by him. And then, in two sentences, he’s dispatched entirely from the narrative: “Kader is in New York now. I don’t feel anything for him.”

Kathy Goes to Haiti wasn’t the moneymaker Acker hoped for. The book didn’t really sell. Doyle remembers giving Acker a small advance but Gaysek insists she received nothing. In any case, the financial disappointment made Acker irritable and, while Doyle would later sublet Acker’s apartment on the Lower East Side, by the early ’80s they were no longer really talking. Doyle was involved in other projects and Acker had moved on entirely by that point—she had signed with Grove Press, which published Blood and Guts (and who would, years later, reprint Kathy Goes to Haiti in an omnibus volume called Literal Madness), and in 1984, she moved to England, where she would become a celebrity. After that, the next time she returned to Toronto, in 1988, the city and its art and literary scenes had changed significantly. Acker didn’t read at a gallery or in a loft but at the International Festival of Authors. What hadn’t changed, for Acker’s readers, was the example she represented. As Doyle put it, almost 40 years after they first met, “Her work is sexual, feminist, immersive and kind of psychological gothic in ways that make you feel a lot of permission and entitlement. She’s a very empowering writer.”

Jason McBride is a Toronto-based freelance writer and editor. His work has appeared in Toronto Life, New York, the New York Times Magazine, the Globe and Mail, Cinema Scope, the Believer and many other publications. He is currently working on Kathy Acker: Her Revolutionary Life and Work, the first authorized biography of the late American writer.

This article is adapted from the Fall 2016 issue of Canadian Art.

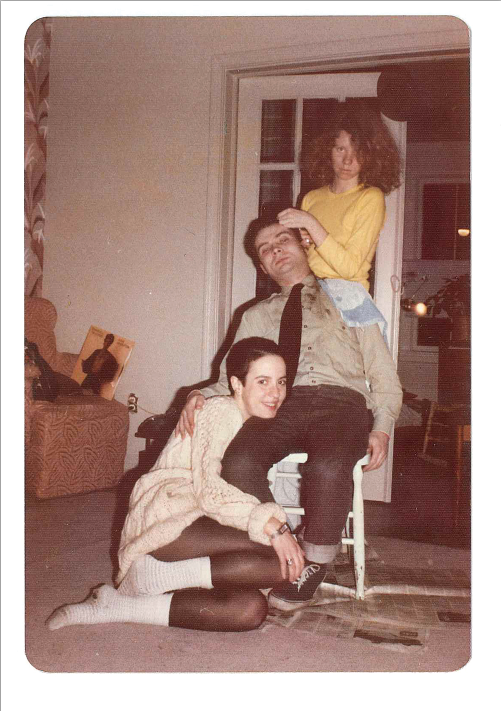

Kathy Acker (seated on floor) with Andy Paterson and Judith Doyle in Doyle’s Toronto apartment in 1979. Courtesy Judith Doyle.

Kathy Acker (seated on floor) with Andy Paterson and Judith Doyle in Doyle’s Toronto apartment in 1979. Courtesy Judith Doyle.