“Paris Syndrome” is a strange, disorienting form of culture shock. Japanese visitors arrive in Paris expecting to find the mythic city of lights and love, and instead confront mundane reality, replete with surly waiters and a chaotic metro. Their disappointment can be overwhelming. It’s rumoured that the Japanese Embassy in Paris has even set up a 24-hour helpline to assist the dozen or so tourists per year who suffer psychiatric breakdowns.

It is this Paris, the one that imparts feelings of depression, delusion and panic, that provides the sentimental backdrop for a scene of romantic disconnect in the pair of manga-informed lightboxes created by Montreal-born artist Julien Ceccaldi for the 2016 Berlin Biennale. In a gleaming-white room, a cadaverous figure in deshabille barely conceals his swelling arousal as he licks a macaron and looks longingly at a man with bulging muscles and a shapely derriere. Through one window, we see the legs of the Eiffel Tower—but much too close, as if the room were located inside it. Through another, we see a cherry-blossom tree (in Japan, a symbol of the fragile beauty of life), its petals floating away on a breeze.

The sense of discomfort in the scene intensifies after we learn that the characters are based on real-life murderers Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, who killed 14-year-old Bobby Franks in 1924 as part of a perverse game—or, rather, on how the pair is depicted in Tom Kalin’s film Swoon (1992), which, unlike Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) and Richard Fleischer’s Compulsion (1959), highlights the gay relationship between the Nietszche-obsessed University of Chicago students, whose codependency was a driving factor in their crime. Versions of the characters also appeared in Ceccaldi’s 2014 comic book Less Than Dust, and in “King and Slave,” his 2016 exhibition at Jenny’s in Los Angeles.

Ceccaldi is a romantic—“not hopeless,” he says, but “foolish.” Like his favourite character in Riyoko Ikeda’s manga Brother, Dear Brother (1975), a popular girl styled after Marie Antoinette and obsessed with her adolescent love, he sometimes has trouble letting go. He confesses that personal insecurities often inspire the anxieties that plague the pointy-chinned, scantily dressed fashion victims that populate his comics, such as “Self-Doubt in the Club.”

Though the last three years have brought him a whirlwind of professional successes—he has been in exhibitions in cities including New York, Berlin, Zurich, Geneva and Los Angeles, drawn horoscopes for fashion label Kenzo and been on the cover of Artforum—Ceccaldi still feels like something of an outsider. “There’s always been a part of me that’s not fully at home anywhere,” he discloses. Despite mounting accomplishments in his own life, the artist remains attracted to the stories that are tragic. In a mixed-up way, they keep him steady.

This spotlight article, adapted from the Fall 2016 issue of Canadian Art, has been generously supported by the RBC Emerging Artists Project.

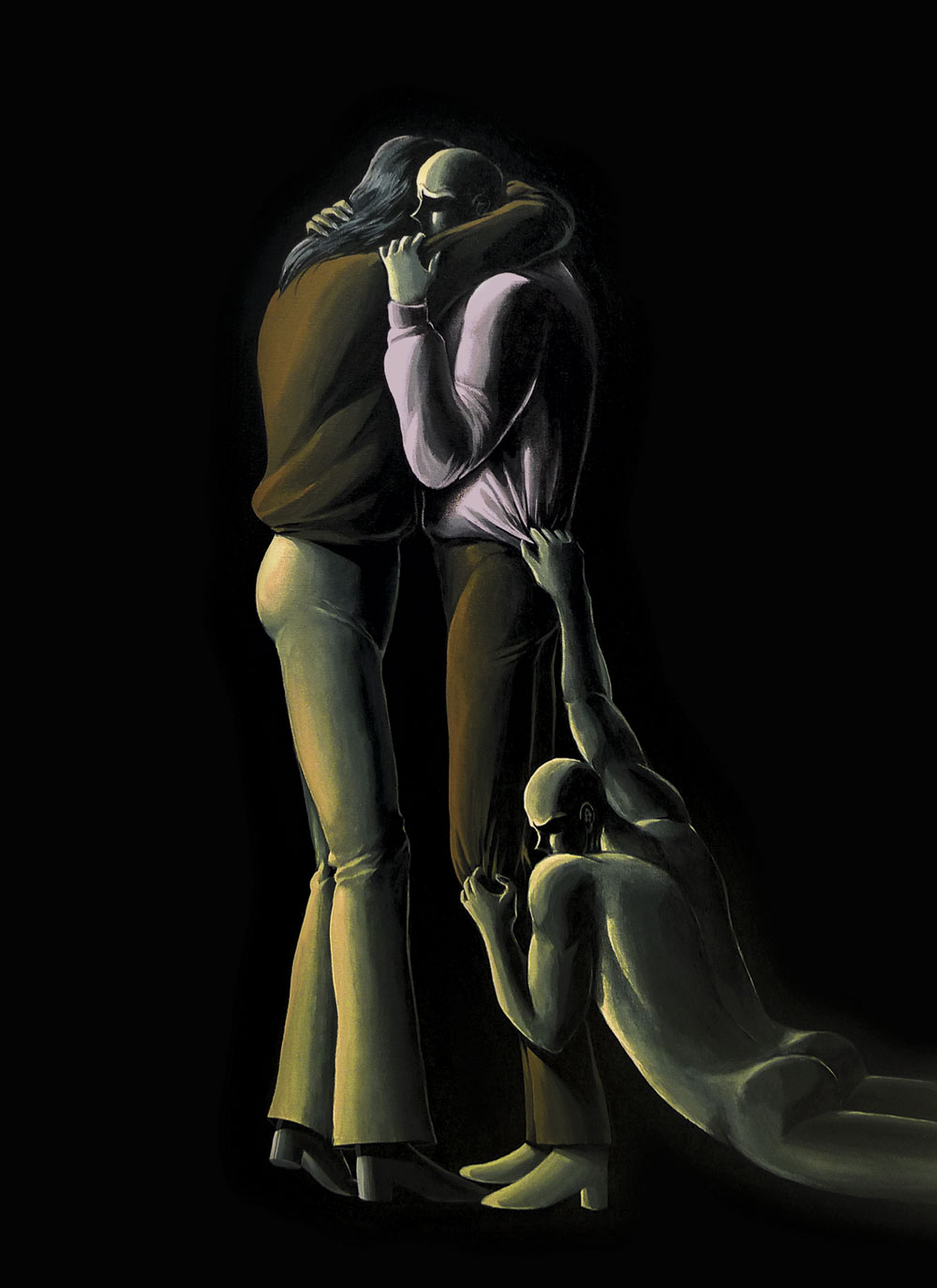

Julien Ceccaldi, Chiaroscuro, 2015. Acrylic on canvas, 101.6 x 76 cm.

Julien Ceccaldi, Chiaroscuro, 2015. Acrylic on canvas, 101.6 x 76 cm.

Julien Ceccaldi, Monument Left, 2016. Digital print, acrylic glass, acrylic paint, aluminum and LED lights. Courtesy Jenny’s, Los Angeles. Photo: Timo Ohler.

Julien Ceccaldi, Monument Left, 2016. Digital print, acrylic glass, acrylic paint, aluminum and LED lights. Courtesy Jenny’s, Los Angeles. Photo: Timo Ohler.

Julien Ceccaldi, Monument Right, 2016. Digital print, acrylic glass, acrylic paint, aluminum and LED lights. Courtesy Jenny’s, Los Angeles. Photo: Timo Ohler.

Julien Ceccaldi, Monument Right, 2016. Digital print, acrylic glass, acrylic paint, aluminum and LED lights. Courtesy Jenny’s, Los Angeles. Photo: Timo Ohler.