It’s a hot summer day in 1971, a week before the opening of Joyce Wieland’s exhibition “True Patriot Love,” the National Gallery of Canada’s first retrospective of a living female artist. Wieland and the show’s curator, Pierre Théberge, are planning last-minute details in the unlikeliest of places: the office of Jan Van Dierendonck, the chef of the parliamentary restaurant.

For weeks, Van Dierendonck has been creating Arctic Passion Cake, a three-foot-tall, six-foot-wide white Styrofoam sugar sculpture that will be one of 35 works in the exhibition. Shaped like an iceberg, it is a giant confection of Canadian topography. It features glaciers, vistas, valleys and peaks made of icing, and includes a candied coat of arms for each province.

“I sleep with this thing now,” Van Dierendonck says, presenting the sculpture to Wieland. He has created it according to her specfications, but during long weeks of work he’s added some of his own flourishes, which Wieland recognizes and embraces. “What else can you do?” she asks Van Dierendonck. “It’s your work of art.”

Although Arctic Passion Cake looks frothy, the message it delivers is anything but. Only nine months after the October Crisis and the invocation of the War Measures Act, the prospect of Quebec sovereignty is a haunting concern, especially in Ottawa. Wieland doesn’t dodge the issue; national unity is one of the key subjects at the core of “True Patriot Love.”

The other is the need for environmental awareness. In the wake of recently commissioned hydroelectric developments for the subarctic region of James Bay, a new national anxiety about northern ecosystems’ industrial degradation has begun to simmer. While few Canadians talk about nature’s fragility, it is a subject—along with feminism and national harmony—that consumes Wieland. In his book A Survey (1970), Wieland’s husband, Michael Snow, describes her as a “filmmaker, collagist, painter and pioneer lay ecologist.” In Arctic Passion Cake, she drives home the point. For her, the environment, women’s issues, art and Canada are inextricably linked.

Wieland asks Van Dierendonck for one last thing: a sugar figurine to top off the cake, like a nuptial ornament. She tells him about The Spirit of Canada Suckles the French And English Beavers (1971), a small bronze sculpture that will appear in “True Patriot Love.” Like a religious allegory of charity, the piece features a nursing woman; but rather than suckling cherubs, she has a beaver at each breast. Van Dierendonck asks Wieland for pictures and sets to work.

“I think of Canada as female,” Wieland said to the press before the launch of “True Patriot Love.” Her words best explain why, in its 40th anniversary year, the show is most often remembered as a feminist milestone.

But not by all. Théberge, the director of the National Gallery from 1998 until early 2009, disagrees. “I have always thought it was such a stupid thing to characterize the exhibition that way.” In a recent interview, he said, “To me, Wieland was an artist first, not a woman first. She did not hide her sexuality at all. But that was not the exhibition’s point.”

In a book she created to accompany “True Patriot Love,” Wieland holds to this wide view. For her, the show’s objective was to reinterpret “everything from the trillium to the name of the country…to renew and begin to invent its future.” She enlisted talent from across Canada. In Halifax, she hired Joan McGregor, the prize embroiderer of the Atlantic Winter Fair. In Dartmouth, she recruited the award-winning knitter Valerie McMillin. In Cheticamp, she found a group that made Acadian hooked rugs. Aided by them and others, Wieland planned “True Patriot Love” to seduce viewers into falling in love with Canada while also alerting them to the peril it faced. Through art, she believed, “The positive energies and people coming together would release the country from its fate.”

In 1971, Wieland was at the top of her game. She and Snow had lived in New York since 1962, and she had built a reputation there as a leading experimental filmmaker. Earlier, in Toronto—her hometown—Wieland had won praise for combining abstract-expressionist and pop sensibilities in her paintings. As “True Patriot Love” opened, her canvases could be found in museums across Canada and her film works were included in the collections of international institutions like the Museum of Modern Art, the Royal Belgium Film Archives and the Austrian Film Archives.

Wieland created her first feature-length work, Reason over Passion, after making a series of shorts that included Water Sark (1965) and Rat Life and Diet in North America (1968). The film made its European debut at the 1970 Cannes Film Festival. A euphoric work of nationalism, it celebrated Canada’s landscape while exploring bilingualism and national symbolism. The film also featured footage of the newly elected prime minister, Pierre Trudeau, that Wieland had shot at the 1968 Liberal leadership convention.

The artist had been attracted to the debonair, worldly Trudeau since 1967, when he told television cameras that “The state has no place in the nation’s bedrooms.” His rise to power in Canada coincided with Wieland’s growing disenchantment toward American politics—the early-1960s race riots, John F. Kennedy’s assassination, the country’s expanding military presence in Vietnam. Increasingly, she had come to believe that Canada was distinct and progressive compared to its southerly neighbour.

Joyce Wieland, Reason over Passion, 1968, quilted cotton, 2.56 m x 3.02 m x 8 cm. Collection National Gallery of Canada. Photo: National Gallery of Canada.

Joyce Wieland, Reason over Passion, 1968, quilted cotton, 2.56 m x 3.02 m x 8 cm. Collection National Gallery of Canada. Photo: National Gallery of Canada.

It was a view she shared with other left-leaning Canadian intellectuals (James Laxer, Abraham Rotstein and Margaret Atwood, among others) who identified themselves as “new nationalists.” They saw Canada as a territory double colonized—first by the British, then by the Americans—and believed that decolonization and reinvention were necessary for true nationhood.

In New York, it became clear to Wieland that a reformation of Canada demanded a visual celebration of its traditions and events. In the US, pop-art pioneer Larry Rivers mythologized America’s past with paintings like Washington Crossing the Delaware (1953), while Robert Rauschenberg included an image of JFK in his 1964 Retroactive I. Canadian artists lagged behind in the creation of an iconography that celebrated the nation’s history.

Trudeau signalled the possibility of change. In a 1965 essay, “Quebec and the Constitutional Problem,” he suggested that the state should play a role in culture. Inspired by this and by the 1965 inauguration of the new Canadian flag, Wieland began to create soft plastic wall hangings. Her Confedspread (1967), a patchwork of bright colours and shapes commemorating the nation on its centennial, featured the maple leaf.

Just prior to Trudeau’s run for the Liberal Party leadership in 1968, Wieland organized “Canadians Abroad for Trudeau.” She, Snow and the Canadian playwright Mary Mitchell threw a cocktail party in the politician’s honour at New York’s Columbia Pictures Corporation building. In the weeks following, she created one of her most celebrated works as a gift for the prime minister: a quilt featuring his motto, “reason over passion.” Surrounding the embroidered phrase with stuffed and stitched fabric hearts, Wieland fashioned a feminine eroticization of Trudeau’s austere formula and plugged his words into the zeitgeist. With her gift for humour and her genius for turning domestic materials into signs of gender, Wieland established a new platform for dialogue.

“People had heard about ‘True Patriot Love.’ Ordinary people. It wasn’t just an elite show for the in-crowd.”

Théberge had already taken note of Wieland’s audacious originality, having seen her work a year earlier at the Isaacs Gallery in Toronto. “She was not beating anyone’s drum,” he recalls. “She was doing her own stuff. She was funny, and the work was funny. But it was also very tough on certain issues. She and her art were a paradox, and I liked that.”

By late 1969, shortly after the Ottawa film premier of Reason over Passion, Théberge approached Jean Sutherland Boggs, who was appointed the director of the National Gallery in 1966, with the idea of offering Wieland her own show. Boggs had encouraged Théberge and the institution’s other young curators (including Dennis Reid and Brydon Smith) “to do exhibitions that were different and important.” Théberge knew Wieland was exactly the sort of artist that Boggs was after.

In the late afternoon on Dominion Day (now Canada Day), 1971, crowds gathered for the opening ceremonies of “True Patriot Love” on the terrace of the Lorne Building, the boxy glass-and-steel office tower on Elgin Street that housed the National Gallery. Advance press for the exhibition high-lighted Wieland’s plan to dispense with the usual art-opening gravitas. A buzz was in the air. “Never in my life have I seen that kind of excitement about going to the National Gallery—or any sort of big institution,” says the author and journalist Judy Steed, who was collaborating with Wieland on film projects in 1971 and later co-produced the commercial feature The Far Shore. “People had heard about ‘True Patriot Love.’ Ordinary people. It seemed like it wasn’t just an elite show for the in-crowd.”

As the sounds of a 100-piece marching band drew closer, the crowd’s anticipation intensified. Choreographed by Wieland, the musicians marched along Elgin Street, turned onto the terrace and led a procession into the building, stopping in the lobby to play “The Maple Leaf Forever.”

“The opening thad the feel of a heartfelt small-town celebration,” remembers Dennis Reid, a former chief curator of the Art Gallery of Ontario. “Joyce knew how to tap into the kind of grassroots energy that was part of everyday social conventions, like high-school brass bands, Canada Day parades and quilting bees. But never in a way that seemed corny.”

Following Théberge’s initial invitation, it had taken Wieland several months to finalize a vision for her National Gallery exhibition. The success of the Reason over Passion quilt and film had put pressure on her. “But that was a good thing,” says Théberge. “It fuelled her ambition and gave her the confidence to take on the nation.”

As the marching band sounded its last note, visitors experienced a scene unprecedented in the National Gallery. As part of an innovative live-animal art installation, a dozen ducks splashed in a cordoned-off blue plastic pool, while a musky scent of new-mown hay and Siberian moss wafted through the air—a homemade artwork-fragrance called Sweet Beaver: The Perfume of Canadian Liberation that Wieland sold at the show in small bottles. The museum became a woodland. As Théberge explains, these sensory components transformed Wieland’s show; rather than a series of works hanging on walls, it was “a total art experience.”

Opening of the "True Patriot Love" exhibition, on July 1, 1971. Photo: Robert Ragsdale.

Opening of the "True Patriot Love" exhibition, on July 1, 1971. Photo: Robert Ragsdale.

“Wieland had an interest in manufacturing a complete-art environment,” says Elizabeth Legge, a University of Toronto art professor. Much like Joseph Beuys in Europe, Andy Warhol in the US and N.E. Thing Co. in Canada, she wanted her viewers to be immersed. But unlike other artists, who tended to make ultra-cerebral spaces, “hers was more like this big sandbox or playground—a high-cultural version of the Electric Circus.”

“True Patriot Love” continued the exercise Wieland had started in 1968 with Reason over Passion, of transforming feminine craft into a powerful vehicle for communication. Collaboratively constructed fabric works—some knit, some hooked, some embroidered, some quilted—celebrated and questioned Canada and offered a new iconography. Spectators stood before O Canada Animation (1970–71), which depicts lush, red lips singing the national anthem. Montcalm’s Last Letter/Wolfe’s Last Letter (1971), a sewn rendition of the final correspondence of the Marquis de Montcalm and General James Wolfe, put the history of Quebec in a new light. In Flag Arrangement (1970–71), knit versions of the Canadian flag, presented in four separate shapes and sizes, brought glory to the maple leaf.

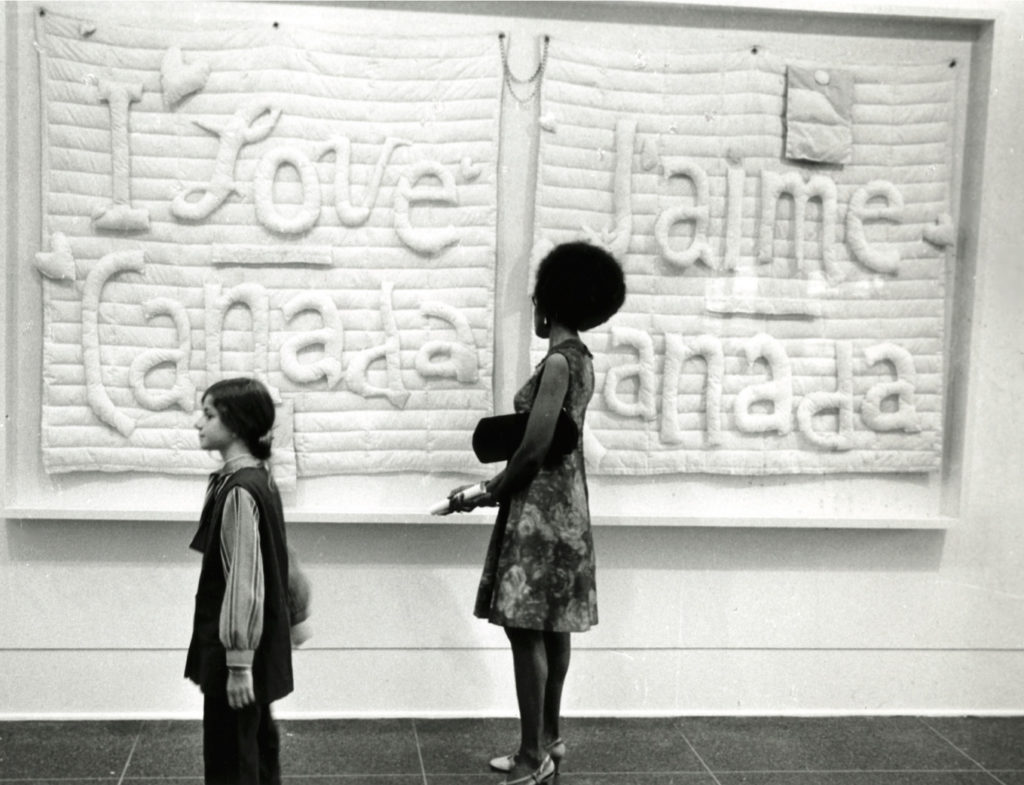

Wieland’s The Water Quilt (1970–71) was a message of warning. The work comprised 64 square cushions, each adorned with a flap embroidered with an Arctic flower; these hid photo reproductions of text from James Laxer’s The Energy Poker Game, a topical book that outlined the danger of selling domestic natural resources to the US. In another cautionary work, I Love Canada – J’aime Canada (1969), a metal chain linked two quilts that exhibited the title words in French and English. Echoing the bilingual display, a small embroidered panel on each quilt read: “Death to U.S. Technological Imperialism” and “A Bas L’impérialisme Technologicque [sic] des E-U.”

Viewers marvelled. Journalist Robert Fulford says, “Think about the time—how many artists used any medium except painting and drawing? For the most part, painters painted, sculptors sculpted, artists stuck to the materials they used in art college. Joyce was going in about four different directions, in a way that managed to feel fresh, free, interesting and engaging.”

Not only did Wieland allow herself to play on a field larger than ever before, but she also used the space of the National Gallery to articulate the idea that art could be participatory, patriotic and about much more than just painting. For many, like Reid, “each piece was more jaw-dropping than the next. In all her work, somehow, the intensity of her celebration ended up in the subtlest way being an interrogation.”

The humour so integral to “True Patriot Love” genuinely disturbed its audience.

“Ardent art for unity’s sake” was the headline of Kay Kritzwiser’s laudatory review in the Globe and Mail. Equally admiring in his praise, Fulford wrote in the Toronto Daily Star that the National Gallery’s support of Wieland marked a moment of new possibilities for Canadian art. “Perhaps the message is that this generation of artists has a special task: to create Canadian art as an independent entity.”

Not everyone welcomed the questions Wieland raised, however. As the Concordia professor Johanne Sloan has written, “True Patriot Love” polarized Canadians who could not agree whether it was “serious or a farce, sophisticated art or the opposite, whether it was celebrating or mocking Canada, whether it was anti-American or proto-American.”

On the day of the show’s opening, demonstrators protested outside the Lorne Building, waving placards emblazoned with “True Patriot Love?” They insisted that the Canada Council should not have been supporting Wieland, who chose to live in the US. And there was anger inside the exhibition, too. “People didn’t know what to make of The Water Quilt,” says Kay Armatage, a University of Toronto professor and the director of Artist on Fire, a documentary about Wieland. “Even the leftists were appalled that she could treat such serious issues in such unconventional ways.”

In his nationally syndicated column, commentator Anthony Westell described “True Patriot Love” as a “cheap patriotic claptrap…. A depressing reminder of all that is least attractive about Canadian nationalism.” Tom Rossiter declared it a “new wave of Canadian nationalism taken to its ultimate absurdity” in the Saturday Citizen. “Whimsy Over Passion” was the title of a review in Time Canada, in which Geoffrey James wrote that the net result of the show was a “slightly forced kind of gaiety.”

The anger around the exhibition was slow to dissipate. The most vitriolic criticism of “True Patriot Love” came in 1974 when the former artscanada editor Barry Lord, in his book The History of Painting in Canada, called the exhibition a “burlesque of national symbols” that was a slap in the face to patriotic citizens. “Scratch the surface of Wieland’s work,” he wrote, “and it was actually US pop art using Canadian symbols.”

The humour so integral to “True Patriot Love” genuinely disturbed its audience. “I would never say she was a satirist,” says Fulford. “On the other hand, there’s an element of satire.” Unlike the soft sculptures of everyday objects that Claes Oldenburg began making in the 1960s, the wit of Wieland’s art lacked an obvious explanation. “Oldenberg was a man who could be using steel if he wanted to, but he made works that were soft. That’s deeply ironic and skeptical about the rhetoric of mastery,” says Legge. Wieland, as a woman producing quilts, cakes and kitschy bronzes, “sailed very close to the wind. She didn’t give you the comfort of irony. It was part of her genius.”

In the 40 years since “True Patriot Love,” it has become clear that Wieland—whose life was cut short in 1998 when she died of Alzheimer’s disease at 66—pushed the boundaries of what constitutes visual experience in art. She was a game changer. “Today, the transformation of an institutional space is business as usual in the art world,” says Marc Mayer, the current director of the National Gallery. “Wieland was at the vanguard of doing such things in Canada.” Now, gallery-goers who see quilts hanging on walls are not the slightest bit disturbed or surprised. This, too, is thanks to Wieland. With “True Patriot Love,” says Fulford, “There was a breakdown of visual arts.”

The prescience and significance of Wieland’s environmentalism is also clear to us now. As Steed puts it, “She was a popularizer trying to bring Canadians messages from academics and intellectuals who were identifying these issues—messages that were not popular notions at all then, but ones that are mainstream concerns today.”

“True Patriot Love” altered the course of Canadian art. It also marked Wieland’s emergence as a national figure, as she brought a startlingly original voice to express a timely idea of national identity. Like the politician she mythologized in art, her legacy is one that haunts us still.

Joyce Wieland in New York, May, 1964. Photo: John Reeves.

Joyce Wieland in New York, May, 1964. Photo: John Reeves.