“The Power of the World always works in circles,” said the Lakota Sioux wise man Black Elk,” and everything tries to be around.” The circle, according to the Austrian psychoanalyst C.G. Jung, is humanity’s collective symbol of psychic wholeness. The circle—trying to be round, trying to be well rounded—circumscribes the 30-year career of artist and filmmaker Joyce Wieland, the first living Canadian female to be granted a retrospective by the Art Gallery of Ontario. Wieland herself is both rounded and well rounded, a plump woman whose physical form reminds one of her softly inflated motherly quilts. At a visit last fall to the University of Toronto’s Innis College to screen films she shot years ago but has only recently completed, she was wearing a black sheath over her rounded contours, and she was wearing blue rhinestone circles, sparkling twin hoops that dangled cheerfully from each ear, and she was wearing glasses, dramatically doffed and donned, that were also round, and she talked, as she so often does, about the necessity of circular integration, about combining the demands of life and art, of politics and painting, feelings and films, males and females, reason and passion.

Even when painting the most powerful portion of the male anatomy (Balling, 1961), this most Canadian of Canadian artist, this most feminine of feminist filmmakers, a woman who has been called everything from a whimsical poseur to an earth mother to a shaman, sees the phallus hermaphroditically, as a rounded and strangely passive and oddly feminine and eerily welcoming shape: in the painterly penises of the world of Joyce Wieland, a womb is struggling to be born. In Wieland’s static visual work, all yang seeks to become yin: in her films, the male strives for absorption into the female. Male artists—even and especially one of Wieland’s acknowledged early sources, Willem de Kooning—tend to treat absorption by the female as an act of conspicuous consumption, as a retrograde perversion all too apt to be accompanied by the gnashing mastication of vagina dentata. In her recent paintings Wieland treats the flight into the female as a return to a rococo Eden, as a romantic journey into a mythological paradise, pastel in purity and lambent with love.

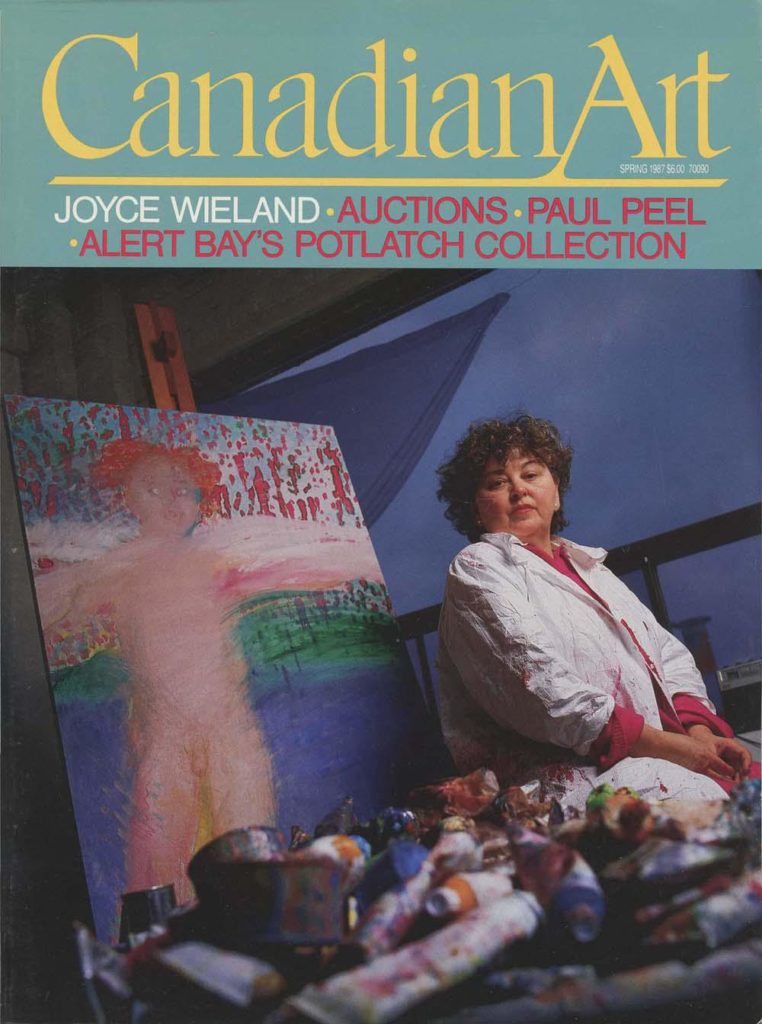

So begins our Spring 1987 cover story. To keep reading, view a PDF of the entire article.