In Joanne Tod’s Toronto studio, a monumental split canvas leans against the wall. It reaches from ceiling to floor and from end to end of the only open wall. Two freshly gessoed canvases lie on the floor in preparation for the next painting and a stack of unassembled stretchers has been deposited by the door. As is often the case, I am stunned by her new paintings. On the one hand they continue many of the issues and ideas developed in her earlier work. On the other, they involve an entirely new set of criteria. There are few artists in Canada today who are willing to continue to expand the parameters of their activity so energetically. Joanne Tod is, without a doubt, one of the most adventurous.

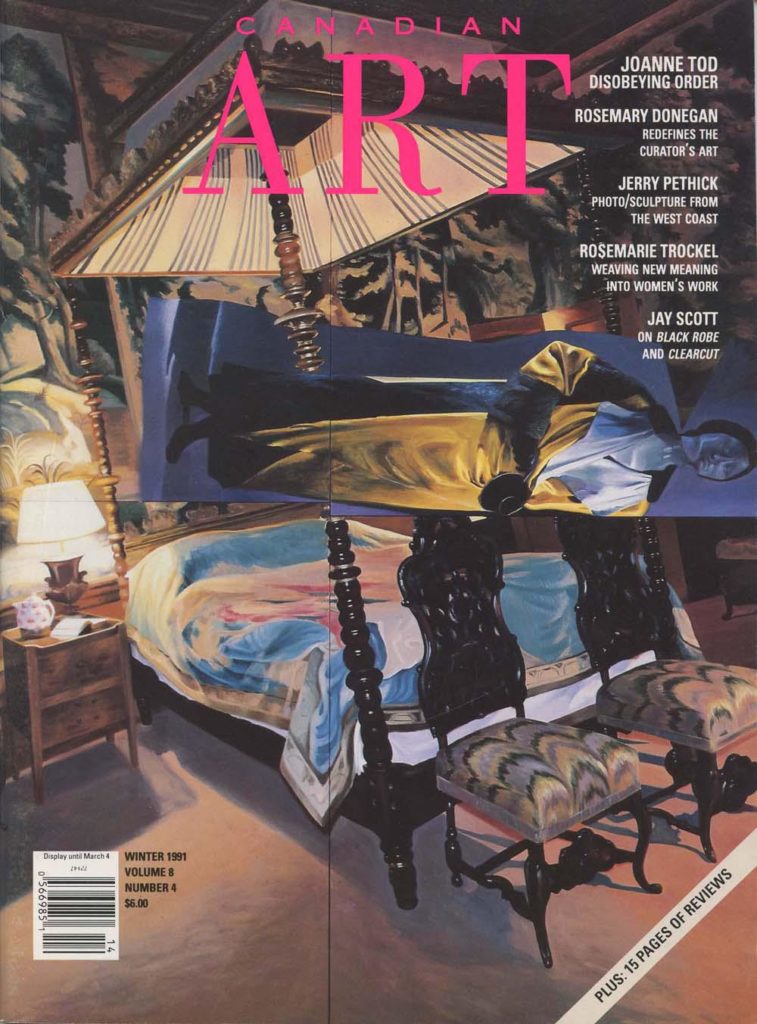

The tall split canvas has an enigmatic title: Shooter with Cliff and Eddy. Its surface offers the image of a domestic interior, a living room, which blithely combines antique and modern, Eastern and Western styles. Images of domestic interiors have been common in Tod’s paintings since the late 1970s; works such as In the Kitchen (1975) superimposes the image of a bound woman from a Japanese pornography magazine over the space of a suburban kitchen, while Self Portrait as Prostitute (1983) presents a lifeless, upper middle-class dining room with one of Tod’s most recognizable earlier canvases hanging on the wall. In each instance Tod created an anomalous situation in which a conventional domestic interior is convulsed into meaning by its intersection with a socially charged image.

So begins our Winter 1991 cover story. To keep reading, view a PDF of the entire article.