At first, the work made me uneasy. Partly because of what little I knew about the people photographed: Toronto’s poor and homeless pictured in the street. And partly because of what little I knew about the photographer: Jeff Bierk, of the illustrious Peterborough Bierk family. He is the son of celebrated painter David Bierk and arts advocate Liz Bierk, has an actress sister, a brother who fronted a successful heavy-metal band, another brother who is an NHL goalie and three more who are artists.

What entitled him to document and display the quotidian world of the underprivileged? And yet, who else was? Wasn’t there maybe some value in rendering that visible? Then, how to fairly handle the sales profits? Questions about exploitation hung in the air beside his work, suddenly appearing in galleries all over Toronto in the past few months: at MULHERIN, AC Repair Co. and the Art Museum at the University of Toronto and commissioned for the Scotiabank Contact Photography Festival. But the sly quarter-smile on collaborator James “Jimmy” Evans’s face, staring out from a picture frame, suggested theirs was another sort of relationship altogether.

Jeff Bierk, Jimmy, In My Kitchen, After Nick Bierk & Caravaggio, 2014.

Jeff Bierk, Jimmy, In My Kitchen, After Nick Bierk & Caravaggio, 2014.

The work might remind you of “street photography”—junior Garry Winogrands documenting whomever and whatever they find in public spaces like it’s their inalienable right, a practice that’s become ubiquitous in the era of Instagram and the iPhone. But Bierk makes a hard distinction between that and what he does now. He regards the type of work included in recent exhibitions like “Top Left” at MULHERIN as “collaborative portraiture,” the ethics of which have evolved with time and experience, and as his relationships with the people he photographs have deepened.

Five or six years ago, though, he stalked the streets in the fashion of the former. The camera is a tool to help preserve memories, he says. “I especially want to remember people; that’s an impulse that comes naturally from my own experience of death.” After a period of “world-scrambling loss” (his mother, father and lover) and heavy drug addiction, Bierk began photographing Toronto’s homeless, street addicts and poor as a way to make sense of the traumas of his own life.

Consent was always important, he says, but he was immature. “I viewed the exchange, a brief conversation around consent, as a kind of permission to not only take a photograph, but to impose my own narrative on it, put it on a website, on the Internet.” His approach lacked transparency. He hadn’t considered the impact of using the image of someone else’s face to build his own career. “I’d adopted and misapplied the position of many photojournalists who, at the time, were defending their rights to photograph in public. I thought that my right to photograph was the most important thing, and I failed to see or understand the imbalance born from the power I was wielding with a camera and with my own privilege.”

The series Sleep represented a breaking point in his image-making practice, causing him to question the process and the efficacy of his photography as a tool for social change. For that body of work, the consent of the subject was forgone. He would stand over someone he found sleeping on the street, crouch down very close until their face filled the frame, and take a picture. “It felt like I was stealing,” he says. “I was doing this with the notion that the images could serve as some sort of evidence, that invading the space and photographing in such an intrusive and violent way would serve a purpose beyond the act itself.”

He posted some of the images to Instagram and Tumblr, where the work drew sharp criticism for its exploitative nature. At the same time, a publisher offered to make a book from the series. He declined, realizing that by attaching his name and career to that documentation, he was gaining unfairly off the experiences and hardships of others. He’d formed close friendships with many of the people he photographed in his neighbourhood. They hung out together every day in the Back 40, a dead-end alley behind his apartment. They still do. He didn’t want to reproduce the same patterns of exploitation and inequity that had already done these people harm.

Today, Bierk’s photographs focus mainly on his closest friends, he tells me, the crew that regulars the Back 40: Jimmy, Bluenose, Carl, Teacher Joe and a few others. As he’s healed, his practice has moved away from locating his own narrative in the images of others. “My friendships have completely changed the way I make photographs and what my photography is about,” he says. “It’s become much lighter, because of the joy we share, and I don’t feel that the images are much more than an honest expression of beauty, the beauty of life and living in these relationships, the beauty of my friends, the beauty of our experience together.”

Jeff Bierk in collaboration with “Jimmy” James Evans, Donald Evans, Brent, Bluenose and Carl Lance Bonnici, “Top Left” (detail), 2016. Image courtesy MULHERIN.

Jeff Bierk in collaboration with “Jimmy” James Evans, Donald Evans, Brent, Bluenose and Carl Lance Bonnici, “Top Left” (detail), 2016. Image courtesy MULHERIN.

His friendships are often scrutinized by inquirers like art critics—a line of questioning he both understands and finds completely absurd, especially when we “so regularly accept the daily violence of class division.” Discussing that frustration with his partner, the musician Simone Schmidt, she says, “Somehow, not acknowledging the people who live in and work the streets of your neighbourhood is a more believable relationship than hanging out with them.”

Bierk’s images are mostly staged, proceeding with what he calls “a continuous, enthusiastic consent.” He believes in complete transparency regarding the way he makes, uses and exhibits the images of the people he photographs. He’s uncomfortable with the word “subject.” It implies a certain power dynamic, he says. “I wouldn’t take a picture of my brother, my grandmother, or my lover and refer to them as ‘my subject,’ you know? So I don’t speak of my friends that way.” Instead, they are collaborators.

And their collaboration isn’t just rhetoric. They’re engaged in a dialogue about setting, movement, pose and expression. The ideas come from both sides. Sometimes Jimmy will request a particular shot. Sometimes Bierk is the one getting photographed. (Bierk’s own picture did appear alongside those of his friends in a collage-themed work at MULHERIN.) There are certain friends who, for one reason or another, have asked that their photo is never shown. Bierk obliges.

His notion of collaboration extends beyond what you might consider the obvious, practical labour of picture-taking into the unseen: “I recognize that Jimmy, in surviving, in his lived experience, is bringing all of this labour into an image—and that without that, the photograph could never be made. The lived experience of my friends, of my collaborators, is an equally important part of the image-making process as my part.” Sometimes, they pass the camera around, redistributing their roles.

As collaborators, they’re entitled to equal pay. Bierk splits any exhibition fees and profits from sales 50/50 with whomever he worked on the photograph with. For a $3,000 C-print, for example, he recoups the $800 production cost for printing, mounting and framing, leaving $2,200 to halve between the gallery and the artist. So he and his collaborator would make $550 each. For “Top Left,” Bierk’s first show with MULHERIN, gallery director Katharine Mulherin offered to split the sales three ways, so “everyone involved gets their fair share of the pie.”

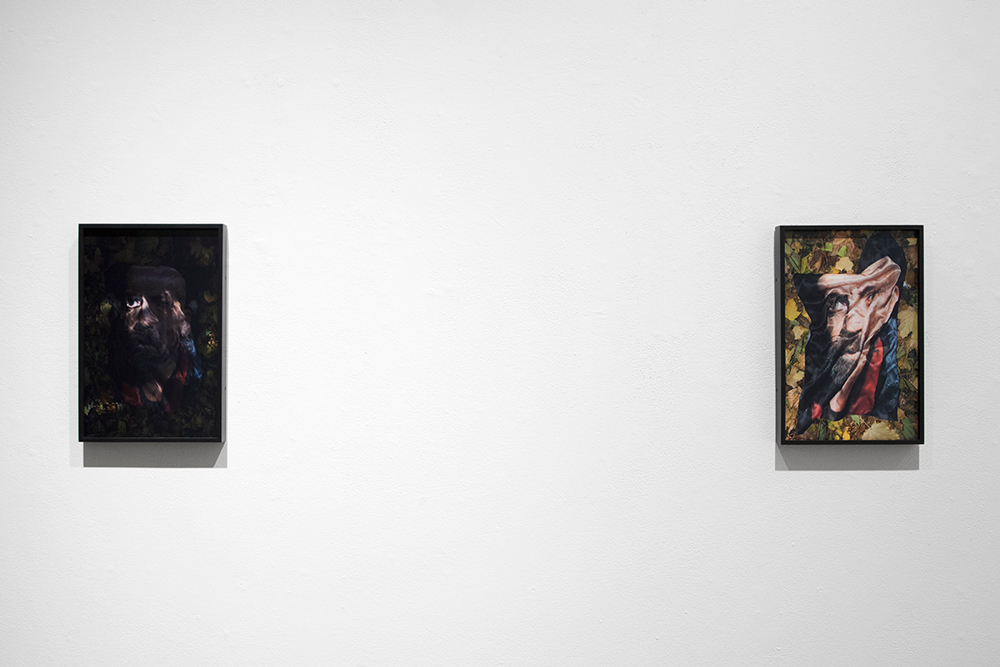

Jeff Bierk, Jimmy (Curtain), Visiting Donny, June 22, 2015 (left), and Jimmy & Brent (right), 2015. Images courtesy MULHERIN.

Jeff Bierk, Jimmy (Curtain), Visiting Donny, June 22, 2015 (left), and Jimmy & Brent (right), 2015. Images courtesy MULHERIN.

Bierk’s photography, of course, isn’t the first art practice to consider inequality and exploitation. At Sweden’s Malmö Konsthall in February 2015, as part of a group show called “The Alien Within: A Living Laboratory of Western Society,” project organizer Anders Carlsson hired two homeless Romanian immigrants he’d encountered on the street to panhandle as performance inside the gallery space. He paid them $600. In the video 160 cm Line Tattooed on 4 People (2000), Spanish artist Santiago Sierra paid four prostitutes the price of a shot of heroin to tattoo a line across their backs. Though these works might elucidate elements of the treachery of everyday exploitations, they do so by reproducing them.

When thinking about exploitation, moral philosophers often discuss vulnerability and asymmetry. A popular hypothetical about wrongful exploitation, imagined by Mikhail Valdman, goes: Hiker B is bitten by a poisonous snake in a remote forest. His death is imminent. Fortunately, Hiker A happens by and offers to sell B the antidote. It retails for $10, but A wants no less than $20,000. B would rather lose his money than his life, so he accepts A’s offer. For Valdman, exploitation is wrongful when you extract excessive benefits from someone who cannot refuse your offer. Some thinkers might ask if we’re treating others as mere ends. Some ponder how fairness is developed in the negotiation of the transaction. In Bierk’s practice, materially speaking, all collaborators benefit equally, but Bierk also gains social capital—a cultural cachet that will enable future opportunities, art-making and otherwise—that cannot be split or remunerated.

I ask him more pointedly: Are these your stories to tell? “I’m not trying to tell anyone’s story,” he says. “I’m trying to articulate a beauty that I see and the only story is the one of the relationship between me and my friends, and it’s such a small sliver of that relationship—what gets shown.”

He speaks about beauty without espousing any particular aesthetic philosophy. Instead, he chases it in two ways: pointing at a large print propped upright across the room, he calls his friend Bluenose “stunning.” He compares him to a Caravaggio painting. Theirs is the beauty of “the pale night, the unhinged mane, the crooked nose,” as Schmidt puts it. He also finds beauty in their strength, surviving beneath the boot of dominant culture. He’s trying to acquaint viewers with the personalities he’s come to cherish.

Jimmy isn’t a symbol to himself or his friends, he says. “The closer you are to someone, the more they are themselves. People’s faces become less symbolic. I feel I can represent people I know well with more honesty, rooted in the truth of who they are, rather than trying to make their image reconcile with a stereotype or trope.” While some projects and shows deal expressly with issues like a lack of shelter beds in Toronto and death and dying on the streets, his practice isn’t foremost about homelessness or poverty—it’s about friendship. It is about connection.

Jeff Bierk, Donny, Silk #2 (left), and Donny, Silk #1 (right), 2013–15. Image courtesy MULHERIN.

Jeff Bierk, Donny, Silk #2 (left), and Donny, Silk #1 (right), 2013–15. Image courtesy MULHERIN.

In On Photography, Susan Sontag writes, “Photographing is essentially an act of non-intervention.” In Regarding the Pain of Others, she goes further, doubting that images of suffering can communicate much good. Bierk agrees. He has an utter lack of faith, he says, that art has the capacity to change the conditions of people in Toronto sleeping on the streets. “If my work allows a middle-class person to feel compassion or see the beauty in someone who has less than them, the most that the work has accomplished is some spiritual change for the viewer, a kind of undoing of part of the violence of a world order in which poor people are blamed and stigmatized for having less.”

He’s found other outlets to feel effective in social struggle, he says, lending his camera, his body and voice to movements that advocate for more shelter beds and racial justice. “I certainly don’t feel that way about a show in an art gallery, an exhibition or art auction. Those platforms are more about getting my friends and me a bit of money and, of course, about expressing beauty.” Sometimes he can use his privileged position to speak directly to power, and sometimes it’s better used to help share wealth.

There’s a passage he points me to in Ariella Azoulay’s The Civil Contract of Photography. Artist and curator Lili Huston-Herterich applied it to an early exhibition of Bierk’s work. The lines are highlighted in the copy Bierk lent me.

“Both the photographer’s vantage point and the process of watching photographs have emerged as only one component within a whole, very complex fabric of relations,” Azoulay writes. “Within its weave, the photographed subject’s act of addressing the spectator bears decisive weight.”

Though we might scrutinize the relationship between the photographer and the photographed, our own position must be added to the calculus. Bierk implores us to see with the eyes of a friend.

Chris Hampton is a freelance writer based in Toronto who thinks mostly about visual art and music. His work has appeared in the Walrus, the New York Times, the Toronto Star and the Globe and Mail, among other publications.