Artist (and now educator) Janet Bellotto is speaking to me via Internet video. I’ve never done this before, and it’s a bit disorienting—there’s just the slightest delay between responses, like talking to someone in another room whom you can hear, but inexactly. There’s an obvious connection/disconnection metaphor here, but more on that later, from Bellotto herself.

The reason I’m speaking to Bellotto via webcam is that I am afraid to visit Dubai. Bellotto teaches art at the sparkling new Zayed University (ZU), in the heart of the “Las Vegas of Arabia.” I was fully prepared to visit her there, and looking forward to it—until I read the fine print about Dubai’s prohibition of prescription drugs.

I take medication for a sleep disorder, a medication thousands of Canadians take every night. It is wholly illegal in Dubai, as are many other common medications available in the West. And according to reliable news sources such as the BBC, Dubai’s border guards have a nasty habit of pinching tourists for carrying medicines as ordinary as arthritis pain relievers and anti-depressants. Google “Dubai” and “prescriptions,” and horror stories of instant imprisonment and rough treatment pop up, from both traditional news media and anecdote-driven travel forums.

When I contacted the United Arab Emirates (UAE) embassy in Ottawa, I was given a long list of doctor’s-note and legal-notarization procedures to follow in order to enter the country with my medications. Fine, I thought, it’s their country. When I contacted Dubai’s own information centre, however, I was given a completely different set of rules to follow. When I spoke to the UAE embassy again, the final word offered to me by the helpful lady on the phone was “ultimately, there is nothing we can do once you are on the ground in Dubai—if the customs officers want to arrest you, they will arrest you, no matter how many letters you have.”

Thank you, Dubai, but no. Hell no.

Thus, the webcam. But even that took some pre-arranging. Bellotto brought along three of her students, young women (men and women learn separately at ZU) with distinct and lively emerging art practices and back- grounds (one of the students later told me that her Bedouin parents were illiterate). I had already looked at a lot of their work in the materials Bellotto had sent me beforehand, and I was struck by how energetic, politicized and beautifully crafted the pieces were (material costs are apparently no object in Dubai).

Nevertheless, once the webcam was warmed up, I had to agree not to show two of the young ladies’ facial features in any forum. In both cases, these rules were laid down by parents before the interview. Furthermore, I agreed with Bellotto in advance to be sensitive to the students’ Muslim beliefs. All that agreeing completely ruined my first, best question: Like, how totally cute is Sheikh Hamdan Bin Mohammed Bin Rashed Al Maktoum?

To protect the students, I’ve decided to identify them simply as Student A, Student B and Student C. I love to cause trouble, but only for myself. Another weird ripple: Bellotto got her job at ZU via webcam. Her interview process was entirely virtual. It makes one wonder how hard it would be to teach via webcam….

But on to the interview. Once all the arrangements were made, and promises promised, I found the three students very candid about the possibilities of pursuing an art career in the UAE, about how they perceived their work as a hybridization of Emirati (indeed, Arabic/Islamic) and Western traditions, and about where the markets for their work are (about one-third at home, two-thirds abroad).

Bellotto herself is forthright, but thoughtful—her careful answers were prompted less, I felt, by paranoia about possible censure than by a natural pensiveness. And since she’s been on the job at ZU for under five years, it all must still feel like a grand adventure—one I envy.

Curse you, Western medicine, for making me an infidel pill-head!

R. M. Vaughan: Janet, how has your own art practice been changed by this new job?

Janet Bellotto: Hmm. Well. It’s been…I wouldn’t say a complete 360-degree turn, but close enough. Over a matter of time, things start infiltrating into the work I’m doing. But my work has always been about water— and I moved to the desert! Ha! But Dubai is on the coast, between the water and the desert, and when you go into the desert, it’s like an arid sea. It makes you look at things in a whole new way, and that, for me, has been very enriching.

RMV: Do you have opportunities to exhibit your own work there?

JB: Oh, a lot! And that’s one of the reasons I’ve stayed. If there wasn’t that community, of so many artists from so many different places, it would be more difficult. It’s made me rethink the idea of audience. And it’s growing.

When I started here four years ago, there were maybe three or five galleries, and then Art Dubai [an art fair] started, and now there are more than 20 good galleries. That makes it possible to start new projects, to do things that are not always as easily possible elsewhere.

RMV: What percentage of your fellow instructors are non-Emirati citizens?

JB: One hundred percent. [Students laugh with Bellotto.] It’s a young country. Zayed University is only 12 years old, and before this time, many students would have gone abroad for university. Also, the people who are born here who do acquire educations tend to go into business, not teaching, or get involved with government—a whole slew of things related to the growth of the country and the sectors that need them.

Now we’ve got a few Emirati faculty, but not in the art department. Not yet, but inevitably there will be.

RMV: How much did you know about Emirati or Arabic/Islamic art traditions before you arrived?

JB: Very, very little. I knew about Dubai before the boom started, and before everyone started talking about it. And it was not what I expected when I got here. I feel like I am continually catching up. The first year was a big learning curve, especially about art traditions in the Gulf.

And I have a few more words of Arabic! Ha! I’m working on it!

RMV: As a Westerner teaching in a non-Western country, at a university primarily staffed by fellow Westerners, what are the concerns around pedagogy versus neo-colonialism?

JB: Even that’s a learning curve. I’m not just enforcing a Western perspective, but learning to balance an Eastern perspective with my own. It’s really important to acknowledge that there are different sensibilities, and I think in our process here, where we involve our students in a lot of practical and research projects—projects that involve heritage and culture—we ask them for their own ideas.

It’s very much true that the students here know a lot about the West. They are not as isolated as we’re led to believe. The UAE in general has always been a trading centre, a hub where a lot of different cultures meet.

What the students are doing here is exploring the middle ground— exploring the culture they grew up with and how to place it within world culture. We spend a lot of time on idea development. They take symbols and forms that surround them, look at what is around them and closest to them, and build on that.

RMV: Student A, tell me about your work.

Student A: I am a 3-D designer, and my major is animation. After art school, my goal is to be one of the faculty at Zayed University.

RMV: So, you’re after Janet’s job?

SA: Ha! Yes! [Much giggling.]

RMV: Is it strange to be taught exclusively by people not from your own country?

SA: Ha! No, I am used to it! Everyone is from a different country here. And, sometimes, yes, I feel that I am teaching them as much as they are teaching me. I am teaching them about my culture.

My next goal is to get a Master’s degree in the U.S., and then to show my work in as many places as I can. When I start to teach, I want to be someone who is not solely a teacher. I want to acquire experience in the art world. I worked recently on Islamic design in Spain. We had a university trip to Spain, and I looked at Islamic design in Spanish buildings. And my graduation project is about women’s lives, using international symbols of male and female.

RMV: Will it be difficult to show that work in the Emirates?

SA: Yes, yes. It is work made for an international audience. I did show some of the work here. Most of the people said it was a strong concept—this animation I made about a man who is angry with a woman. But they said I was presenting the concept in a simple way, and they said they didn’t expect to come and be shocked at a gallery. But that was my goal! Ha!

RMV: Student B, tell me about your practice.

Student B: This is my graduating year, and recently I was in an exhibition at the Dubai International Financial Centre. I created an installation, a massive installation, inspired by living in two separate areas—Dubai and my small hometown.

My work is very minimalist and I’m inspired by architecture and interior design. I started school as an interior-design student, and then changed to art. I felt very restricted as a designer; I didn’t have freedom of expression. There was always a set of principles I had to abide by.

For now, I want to continue creating art, but I want to move into curating. And maybe do a Master’s degree, too.

RMV: If you chose to, could you make a living selling your art in Dubai?

SB: Yes, eventually. I could not now, but people do. I have not had a lot of exhibitions, and I have not sold my work yet. My first exhibition was in Venice last year.

RMV: Wow! That’s a good start. At the Biennale?

SB: Yes, sort of….

JB: It was coinciding with the Biennale. We had an academic trip and a student exhibition near the Biennale.

RMV: Some people work 20 years for that kind of exposure!

SB: Ha! I know, I know. [Much giggling from all three students follows.]

RMV: How does your family feel about you becoming an artist?

SB: They are very supportive. Art in Dubai has developed very rapidly in the last five years, and people are more accepting of art as a profession.

RMV: Student C, it’s your turn. Tell me about your work.

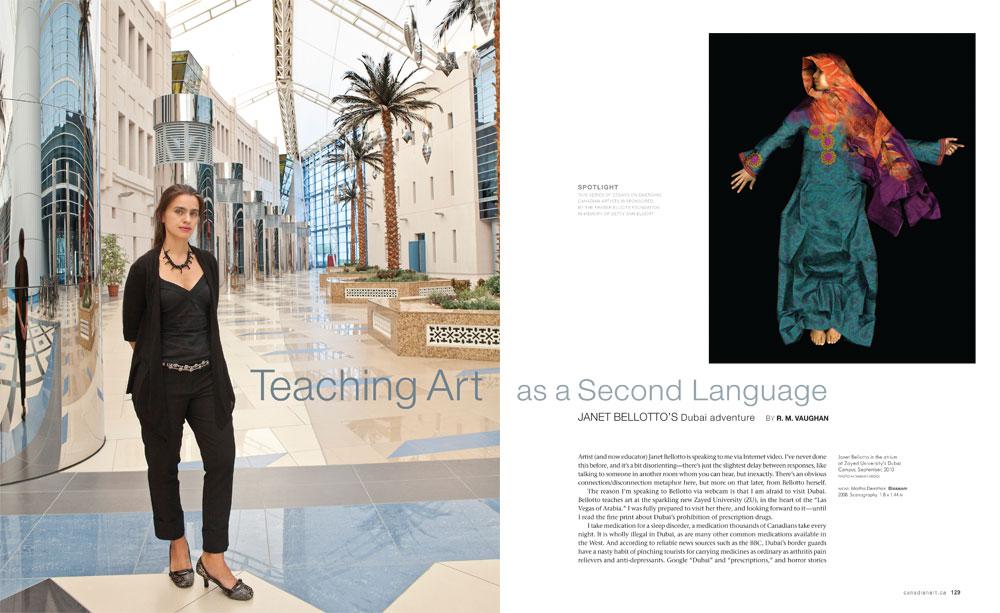

SC: I do a lot of mixed-media work—photography, drawing, painting. Recently, I’ve been doing scanography. Basically, I scan parts of people on a flatbed scanner, and then put the parts together in Photoshop, to create the whole body. It is mostly my family and people around me.

RMV: There’s an idea here in the West—which is probably wrong, so please correct me—that Islamic tradition frowns on representational imagery.

SC: Of the human body?

RMV: Of anything.

SC: Islamic law says that you cannot recreate the human figure in drawings or paintings—but as long as it is a photograph, you are not really recreating. It’s more like capturing, recording. So, photography is accepted, but not really paintings or drawings.

Some of my early works were figurative, and I got comments from people saying that they did not accept the work, because there were human faces and bodies, and that it was not appropriate for me to do that. But I have been told that as long as it is not a full human body, it’s fine. But a full human body is forbidden.

RMV: Janet, what has been your biggest challenge at Zayed University?

JB: Hmm….

SB: Do you want us to leave the room, Janet? [More giggling from students.]

JB: No, ha! No, stay!

I think, as a teacher, you are always trying to find the balance between not pushing your own ideas and methods, and trying to find the bridges between the local culture and Western ideals—especially when we talk about art and theory. I’m always trying to find Eastern counterparts to Western theories.

I didn’t teach full-time until I moved here, so it’s all been a big shift—full-time teaching, the other side of the world and 50-degree days! When I first came here, it was just supposed to be for just a year…and I’m still here.

This is an article from the Winter 2010/11 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.