For centuries Venice was the site of artistic pilgrimages by musicians, poets, novelists and painters from distant lands. What Venice had to offer them—an otherworldly setting like no other, an abundance of history, superb monuments, isolation, slow rhythms, no night life and a monopoly on tourism—is less attractive to today’s artists. However, their followers flock there in annual waves for the renowned film festival, the architecture biennial and the mother of them all, the venerable visual arts Biennale di Venezia, the grande dame of all international biennials, established in 1895. For a few days the international art world enjoys unparalleled networking and partying amidst the national pavilions in the public gardens and at other spectacular site throughout the city, its spirit buoyed by this gentle fantasyland devoid of the urban chaos of rush-hour traffic and schedules geared to the speed of the internet. Venice prevails in all her unhurried glory. The art pilgrims make necessary noises about the fetid canals, the outrageous price of a hotel room the size of a Japanese businessman’s sleeping capsule and the inconvenience of an infernal labyrinth of dead-end streets overcome only by slow boats, safe in the knowledge that when they leave la Serenissima, a less serene world awaits them.

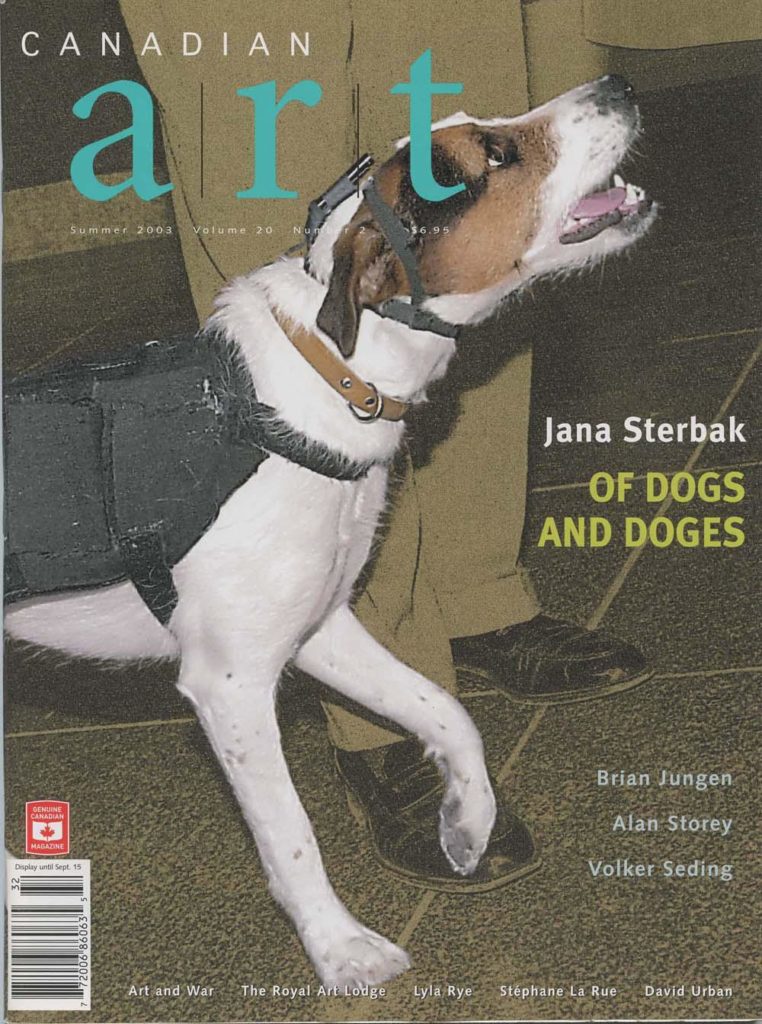

So begins our Summer 2003 cover story on Jana Sterbak’s presentation at the Venice Biennale. To keep reading, view a PDF of the entire article.