Artist James Luna. Photo: Facebook.

I am writing this to honour the life and art of James Luna.

Because, like many very good artists, his life and art were often impossible to untangle, and because he was not only an inspiration for my own writing, but also a friend, I won’t pretend that this is a detached assessment of his career. As a writer, I suppose writing this is my way of processing the shock of his unexpected passing and coming to grips with the magnitude of his achievement. This, in turn, inevitably leads to a calculation of our loss. At the same time, it also feels appropriate to share my reflections and memories with others, many of whom I’m sure are going through their own versions of this process.

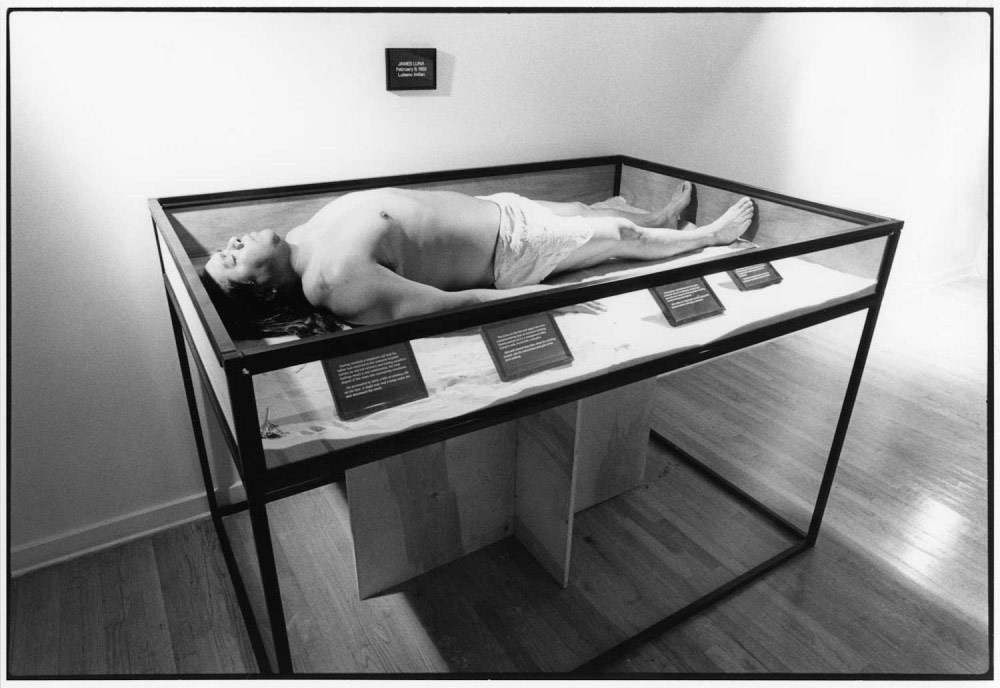

Despite the inescapable personal dimension of writing this remembrance, it is still absolutely necessary to begin with Luna’s art: specifically his best-known work, Artifact Piece. In this performance/installation, which was first staged at the San Diego Museum of Man in 1987 (and then again in 1990, for “The Decade Show” in New York) he lay unmoving for hours in a museum display case. Personal artifacts were placed on display in vitrines nearby. These included everything from his Motown record collection to his divorce papers.

Luna sometimes complained that attention to Artifact Piece too often came at the expense of his later work, and it is certainly the case that his entire career deserves and richly rewards careful attention. That said, Artifact Piece is special. It is one of those works that manages to concentrate many important, emergent ideas into a single gesture at just the right moment—in this case the moment when many Indigenous people were struggling urgently to theorize and express their concerns about their representation in museums. So, while I think there are other of his works that are as good, that combination of prescient timing and flawless execution have made Artifact Piece iconic. It holds its own in importance alongside any of the major works of the institutional critique movement from the latter half of the 20th century.

A photo of James Luna enacting Artifact Piece, first performed in 1987.

A photo of James Luna enacting Artifact Piece, first performed in 1987.

Artifact Piece addressed so many of the key themes that Indigenous artists of Luna’s generation grappled with, including the problems of representation in popular culture and museums and how these systems of representation foreclosed contemporary Indigenous agency. Artifact Piece showed all too clearly how what the critic Jean Fisher described as “the necrophilous codes of the museum” makes corpses out of living Indigenous bodies and cultures.

To the extent that it made explicit the politics of looking, Artifact Piece also ran in parallel with some of the concerns of the feminist discourse of the time. Although the process of objectification of Indigenous people operated through exoticization, the effect was a similar theft of agency. I remember Luna saying a number of times that if he had known how awful it would feel to just lie there and be looked at, he might never have actually done the work.

An important part of Luna’s resistance to this pernicious form of objectification was his insistence on experiences with popular culture and other aspects of modernity not as signs of assimilation, but as valid aspects of his reality as an Indigenous person. In a 1991 article, he wrote that while he once felt torn between two worlds: “In maturity I have come to find it the source of my power, as I can easily move between these places and not feel that I have to be one or the other, that I am an Indian in this modern society.”

Luna, who was of Payómkawichum, Ipai and Mexican heritage, grew up away from the La Jolla Indian Reservation in the North County of San Diego, but moved there as an adult and stayed for the rest of his life. I remember him telling me about his teenage years on Orange County beaches. He said that the surfers would often look at him and assume he was an Indigenous Hawaiian. When they asked which island he was from he’d say, “The big one man. The big one.”

His home at La Jolla was fairly high up on the side of a mountain and Luna kept a single tall palm tree there near the edge of the slope as a reminder of his youth spent at the beach.

Luna loved to travel and he loved to be at home at La Jolla. I think his career was fundamentally about the intersection—often in the form of his own performing body—between the place he lived and the many places he travelled.

He was generous with the power he accrued from being able to move between worlds, using his success to help other Indigenous artists with mentorship and letters of support at times when they faced a great deal of institutionalized resistance to “ethnic content” in their art. A number of Indigenous artists have told me over the years that Luna’s comfort and confidence in the contemporary art world and his ability to address Indigenous issues without apology there inspired them to do the same.

Early in her career, Rebecca Belmore received an Ontario Arts Council grant to visit Luna in La Jolla as a way of helping to complete an education with instruction not then available to her at art school. In 2001 she created a tribute to him, a wall-mounted sculpture titled Mister Luna. Curator Barbara Fisher has described it better than I can: “Mounted way up in a circle of lights, shiny yellow shoes stand for the artist whose name implies light that radiates from the moon. I have rarely found the effect of lights as hopeful and beautiful…” (The installation was later shifted to a half-circle of lights, but the radiance remains.)

Rebecca Belmore, Mister Luna, 2001. Mixed media. Collection of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre. Purchase, Canada Council Acquisition Assistance Fund and Chancellor Richardson Memorial Fund, 2003 (46-005.01). Photo: Paul Litherland.

Rebecca Belmore, Mister Luna, 2001. Mixed media. Collection of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre. Purchase, Canada Council Acquisition Assistance Fund and Chancellor Richardson Memorial Fund, 2003 (46-005.01). Photo: Paul Litherland.

I first met Luna through Belmore, when I interviewed them both at my apartment in Toronto for FUSE magazine back in 2001. I had naively arranged to do the interview the morning after one of Luna’s many Canadian performances. When they failed to show up, I called to see what was happening. The word back was that they had both been up most of the night and that Luna would come only on the condition that there would be waffles. “Of course there will be waffles,” I said. I had no idea how to make waffles, nor any kitchen gadget with which to make them, but when things need to happen there is usually a way. A few phone calls produced a generous friend with a waffle iron and off we went.

Since then our paths have crossed at panels and performances in many places: Banff; Toronto; Kelowna; Portland; Venice; Warwickshire and London. The best and most instructive visits were to his home at La Jolla. My wife Bev Koski and I visited him once in 2004 as part of a research trip for the Compton Verney exhibition “The American West” and again on a sabbatical research trip in 2012. Each time he and Joanna Bigfeather welcomed us with incredible hospitality and we ate, drank and talked long into the night on the patio that sits between the house and the studio.

I didn’t fully understand just how significant La Jolla was to Luna’s practice until that first visit. I saw this in two ways.

The first way was the extent to which his home, studio and grounds made up a contained and coherent aesthetic world composed of all the sorts of items, from treasures to kitsch (or, I suppose, treasured kitsch) that you might see in a Luna performance or installation. The whole place felt charged with energy, as though the objects already knew what to do and were just waiting to be sent into action.

The second, and more important, way was how clear it became that his performances were not the work of a detached observer commenting on the joys and tribulations of his community. This was a reality he was enmeshed in daily. During both visits he made a point of driving us around the rez in his truck, showing us important places and introducing us to people; especially “the boys,” a group of men he hung around with regularly.

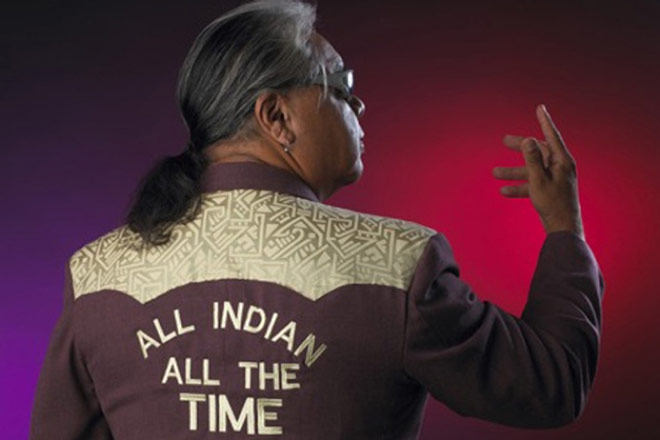

James Luna, All Indian All the Time (detail), 2006. Photo: William Gullette.

James Luna, All Indian All the Time (detail), 2006. Photo: William Gullette.

On our first visit, we spent some time at the rez bar and got to meet an important friend, Willie Nelson, who Luna spoke about frequently and admired for his knowledge of language and culture. By that point in the evening I may have been a bit too drunk to fully appreciate all this. I know I was drunk because at some point Luna convinced me it would be a good idea if we both put brightly coloured inflatable pool rings on our heads and pretend they were sombreros. Yes, there are pictures. No, you can’t see them. And, yes, he looks cool and ironic with a pool ring on his head. And, no, I do not.

The next time we visited, Willie Nelson had died. Luna drove us past his grave so we could pay our respects and reflect on the loss to the community.

Luna had made a commitment to being unflinching in depicting the issues his community struggles with. “I do not make pretty art,” he wrote, “I make art about life here on La Jolla Reservation and many times that life is not pretty … our problems are not unique, they exist in other Indian communities; that is the Indian unity that I know.” He understood that these problems could not be addressed if they could not be discussed, so he found ways to do that which were direct, accessible and artistically rich.

The work that hits me the hardest in this regard is the performance In My Dreams, from 1996. I can’t do justice to the entire performance here, but there is a section in the middle that is devastating. After earlier watching the artist eat a meal of spam dressed up with ketchup and mustard and then taking his insulin shot, Luna re-appears on a stationary exercise bicycle in front of a projection of scenes from biker movies. He is dressed in Indian kitsch, including a dyed chicken feather bonnet. Nevertheless, he gamely gets to work on the bicycle, pedalling and getting nowhere, while a constantly receding Hollywood highway gives the illusion of forward movement.

As he rides he opens a beer and lights a cigarette. We want to laugh at the absurdity of this in the midst of an exercise regimen and at the silly feathers that suggest a travesty of actual Indigenous traditions, but the tragedy just below the surface makes that uncomfortable. A self-defeating effort at self-improvement somehow seems to compound the tragedy. Then, in what I think is one of the most inspired moments in any of his performances, he brings out a pair of crutches that are also decorated with dyed feathers and raises them out to his sides as though they are wings.

That gesture shatters me every time. If there is one theme Indigenous artistic and oral traditions have in common it is that of transformation. Supernatural beings transform themselves and human beings access supernatural powers by transforming into animal forms. It is fundamental. Can we dare to hope that dyed chicken feathers and crutches can be transformed into wings? That kitsch can become real culture? That someone struggling without forward movement might take flight? It seems that the performance dares us to hope that might be so. It’s not much hope, it seems to suggest, but it’s what we’ve got.

Being conscious of Luna’s wish to have the full range of his career appreciated, I don’t want to conclude without mentioning a more recent body of his work that I think is as good as anything he has ever done. This is We Become Them, which exists as a series of performance gestures and as a 2011 series of photographs in which found images of masks from a book on Northwest Coast art are paired with photos of the artist imitating them using only his facial expressions. The work was inspired by a comment by Haida artist Robert Davidson, who said that traditionally when masks were danced ceremonially, they were not understood to represent particular beings, but rather as allowing the dancer to become those beings.

It is fascinating to compare the images of We Become Them and register both the skill of the carvers and Luna’s own mastery over his medium, which, in this case, is nothing but his own body. On one hand, it is a kind of performer’s bravura masterwork, a challenge that leaves no room for props or tricks to carry the work. At the same time, it seems to me to propose that art practice might be used to do art history, but in a way that falls outside art history’s usual tool, writing. In the place of writing, we have a sensuous bodily mimesis that hopes to bridge a gap of cultural and historical distance to create a momentary fusion of identity. To me, this is a remarkable thing to attempt, let alone to carry off so convincingly.

James Luna was larger than life, and no memorial can really come to a conclusion that would do justice to all that means. It can only end. But this one can’t end without a thank you. There should be so many, James, for your hospitality and generosity to Bev and I on so many occasions.

And there is one very personal thank you I cannot end without. When you write about art, you absolutely depend on there being exceptional works of art. It is the one thing you must have if you hope to do your best work. So thank you, James, for your art. I’ve learned so much from struggling to write about it and do it justice. That process has fundamentally shaped who I am and how I think about the world. And although this short memorial will end, I know that I will be writing and thinking about your art for as long as I am writing and thinking about anything. I won’t be the only one. Your art is going to keep changing the world; we can’t do without it.

Richard William Hill is Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Studies at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver.

A clarification was made to this article on March 7, 2018, to account for differences in earlier and later versions of Rebecca Belmore’s installation Mister Luna.

Artist James Luna. Photo: Facebook.

Artist James Luna. Photo: Facebook.