The world of cartoons and the world of art have a longstanding—and, some might say, deepening—relationship.

From the satirical caricatures of Honoré Daumier in 1830s France to the dry witticisms of Ad Reinhardt’s New York in the 1940s to the boho wanderings of Julie Doucet’s Montreal in the 1990s to the dark, self-conscious jokes of Walter Scott’s delocalized art scene in the 2010s, the gallery and the page have been in dialogue.

In recent months, cartoonist Eric Dyck’s residency at the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery has engaged this tradition in a fresh way.

For the project, Dyck (who is also an art teacher and an ACAD alumnus) has been drawing live in the gallery—or just outside its doors around campus—on a regular basis.

And simultaneously, Dyck has been posting the drawings to the gallery’s Facebook, Twitter and Instagram feeds, as well as livestreaming the drawing sessions there.

In the process, Dyck has captured many of the reactions to art, artists and art galleries that often go unrecorded, including commentary on the legacy of late Blood-tribe cartoonist Everett Soop; questions like, “Is it okay if I come in?” and, “We can go in there?” and, “We have a gallery?” that reflect the lack of connection many members of the public feel to art in general and art galleries in particular; ivory-tower chatter like, “All of the communist governments are related anyways,” and, “My last cigarette was 15,000 km ago,” and, “I am so lost. Because I don’t university.”; and overheard comments that highlight still-prevalent tensions between different cultures on campus.

“Have you looked at some of this ART?” pic.twitter.com/hIRiafMUqq

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) March 2, 2016

“The content of my comic strips for years has been based on eavesdropping or sharing conversations I have with people, and drawing people and situations right there where it is happening,” says Dyck, “So this is very much in my comfort zone.”

Some of the material Dyck has culled from his gallery sittings in recent months—and during an earlier stint in the fall of 2014—ends up on gallery walls, while others inspire scenes in his comic Slaughterhouse Slough, and yet others are reprinted in university newspapers.

“The highlight for me is always sharing,” Dyck says. “People can come and watch me draw live, and in other parts of the university, my drawing is being streamed in the walls. I get repeat visitors, and some people will come back to see if they made the cut.”

On the March afternoon that Canadian Art spoke with Dyck, he was drawing students who were retrieving artwork after it had been stolen in a strange case of art-department theft.

“I’d say because my personal experience has revolved around art galleries and museums for most of my life”—Dyck was formerly a school educator at Calgary’s Glenbow Museum—“a lot of the comics I’ve done in the past have been about conversations had in those spaces.”

University of Lethbridge Art Gallery director/curator Josephine Mills says Dyck is “literally back by popular demand” until April 7.

The reason? During his first cartoonist-in-residence session in fall 2014, Dyck proved to be a real draw for art audiences old and new.

“There is nothing better than artist for attracting attention,” says Mills.

Other initiatives for public engagement at ULAG of late include organizing a drawing bar in the evening and a noon-hour “knit and natter.”

It’s all part of “a whole program of expanding our public engagement activities, and is part of a big research project… where we are looking at what does public engagement involve” in contemporary art in particular.

Mills and her colleagues have even submitted a SSHRC application for a project titled “Am I Allowed in Here?” about how people engage in art.

“A lot of it, for me, is raising the profile of the gallery, [showing] that we actually exist and that there is stuff that people would want to actually do in the gallery—and that, yes, they are allowed in here.”

.@mr_ericdyck is here, drawing live today! Livestream is on Facebook. pic.twitter.com/LGCkFQi6Iv

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) March 19, 2016

Two people walking by: “Hey! It’s Marty!” @mheavyhead pic.twitter.com/RP6VzvfqB0

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) February 29, 2016

Drawing live in the @UofL_FineArts building! pic.twitter.com/syJ9Q8ZPmt

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) February 24, 2016

Drawing live with @mr_ericdyck #MuseumWeek #peopleMW #DogesMW pic.twitter.com/GENz5dYZDr

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) March 29, 2016

Drawings are happening right now! Stop by upstairs in the Helen Christou Gallery. pic.twitter.com/zb6JJA6NBV

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) March 2, 2016

World War III pic.twitter.com/MWWMxBh2yb

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) February 24, 2016

Live drawing right now! pic.twitter.com/3EGu7WjK7b

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) February 24, 2016

Eric is also chatting with gallery visitors — who are also super important people for museums #peopleMW pic.twitter.com/hUI6ku9Wpk

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) March 29, 2016

“Helllloooooo” pic.twitter.com/16qOBfYEDO

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) March 17, 2016

“All of the communist governments…” pic.twitter.com/fUM5osk5zs

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) March 15, 2016

“I am so lost.” pic.twitter.com/davokC7W3w

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) February 24, 2016

.@mr_ericdyck drawing live in the gallery. “No, dude. I am not ‘stoked’.” pic.twitter.com/FRpPyX6Wn8

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) March 24, 2016

“My last cigarette…” pic.twitter.com/WD0Cl9uT2V

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) March 15, 2016

“I get it from my mom.” pic.twitter.com/u52YJXEp46

— Uleth Art Gallery (@ulethartgallery) March 2, 2016

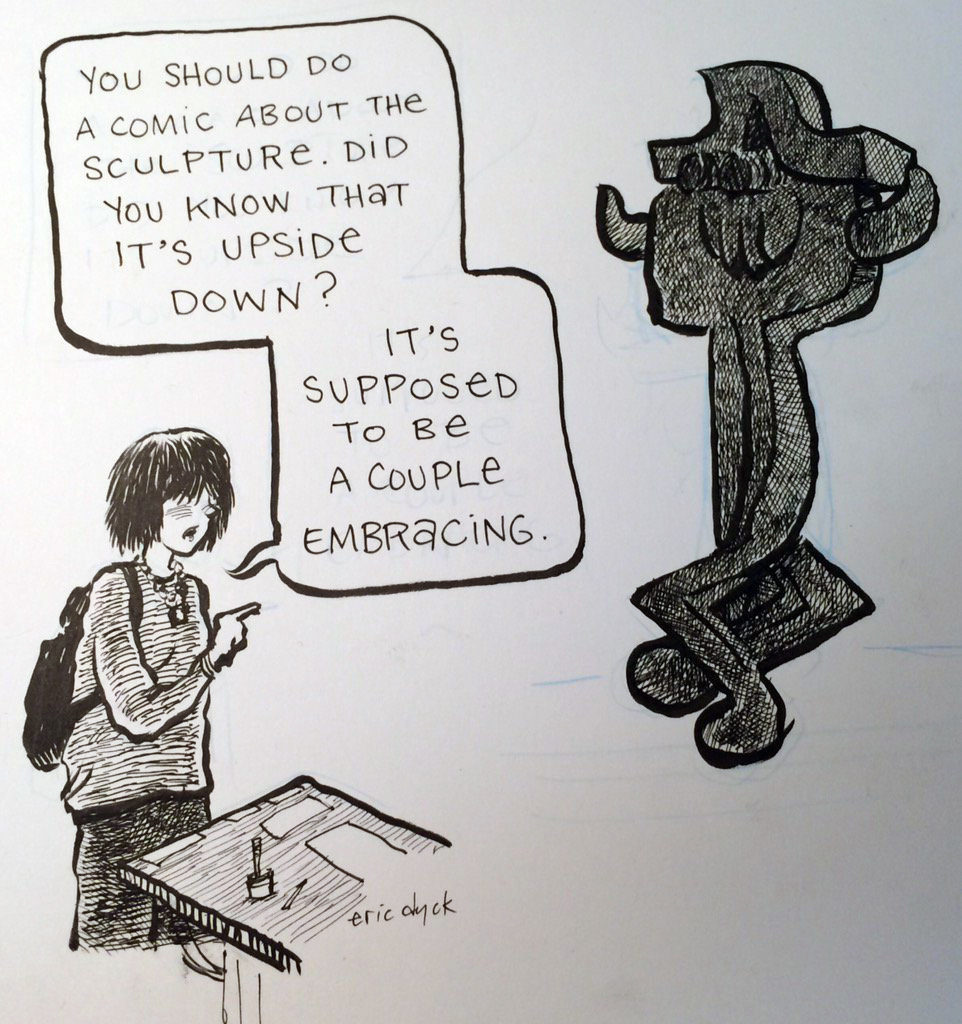

Controversy and misunderstandings about a Sorel Etrog sculpture is just one of the issues cartoonist Eric Dyck has captured during his residency at the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery.

Controversy and misunderstandings about a Sorel Etrog sculpture is just one of the issues cartoonist Eric Dyck has captured during his residency at the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery.