During a happening one evening at the 2011 LIVE performance-art biennial in Vancouver, I watched artist Raymond Boisjoly use a can of Main Street lager to scrape the words Uneasy with the Comfort of Complexity onto the surface of a white wall. It’s a phrase that can help define the Vancouver-based artist’s practice, which is about transmission and process. Inquisitive, sharp, generative and generous, Boisjoly encourages us to alter how we think about the reception of content. Working in photography, language and video, he has become a leader in a generation of emerging contemporary artists asking questions about the ways we look, about how culture is processed and about the value of artistic agency.

Boisjoly’s work tends to redirect, filter and accent our thinking about how we regard and receive culture at large. It also cites, reproduces, distorts and changes the products of other artists, writers, directors and musicians. His process cultivates a context for learning. It questions motivations and raises awareness of how these motivations play into the ways that things are made and seen. His artworks can be read as signposts towards new methodologies that negotiate the state of Indigeneity and why it, more often than not, tends to address others.

Boisjoly studied at Emily Carr University of Art and Design and completed an MFA at the University of British Columbia. During his undergraduate years, he took an introductory course on theory taught by art critic and writer Clint Burnham. Burnham guided the class through texts by canonical cultural theorists such as Roland Barthes. The focus of the class was on learning to understand the thinking and styles of art writers. As Boisjoly recalls, Burnham’s approach created an inspired space of understanding that allowed the students to enter into texts such as Camera Lucida on their own terms. They knew the perspectives, arrangements, trappings and conditions of the theorist before learning the discipline-specific theory itself.

Boisjoly’s Rez Gas (2012–) echoes this lesson. It is a photo series that insists you deal with the materiality of the images themselves before dealing with their subject matter. The photographs document independently owned gas stations found on reserves. They are printed with a sunbleaching technique on black paper and mounted to thick acrylic glass. This printing method does not allow for a standard photography fixative chemical to be introduced to this process and, as a result, delivers the images in a fragile and unstable state. The gas station as subject speaks to Boisjoly’s interest in the vernacular. It represents a space of open and unstructured cultural encounter for Indigenous communities. The makeshift material conditions of the photographs relate directly to the context of their subjects, where localized processes and economics at play within Indigenous systems are pressured to behave within Canadian political and economic norms and increasingly face uncertain futures.

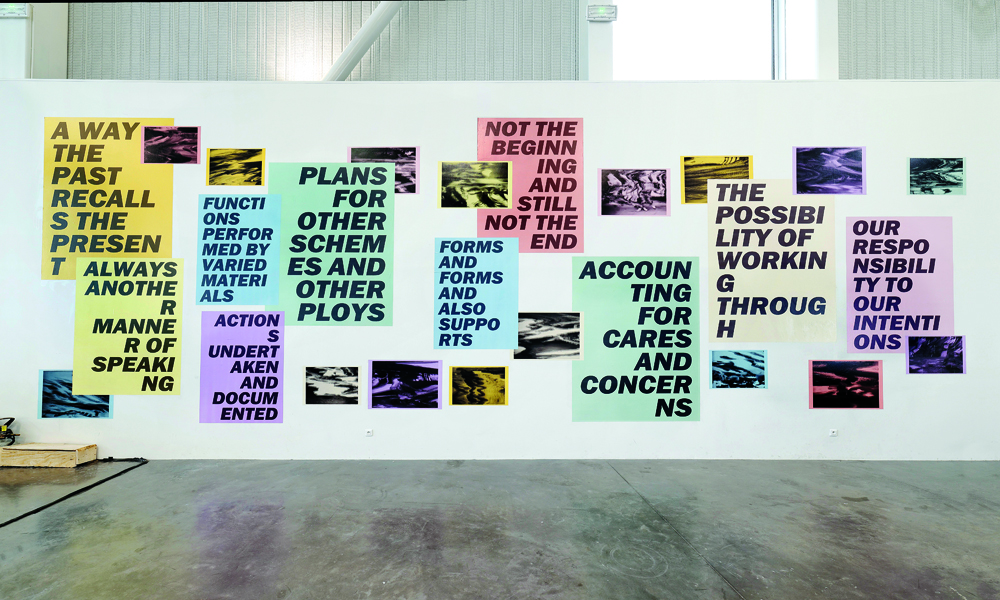

After artists leave school, they face a different kind of learning. Professional life is a merging of practice, local conditions, the international art world and modest production earnings. In 2010, curator Kitty Scott, then director of visual arts at the Banff Centre, invited Boisjoly to visit on a self-directed fellowship. This was learning in a space of trust, in a place where one is not told how to resolve the work, but directed instead to follow on one’s own steam. Boisjoly recalls this time as a definitive, pivotal moment in his practice. During the residency, Scott’s advice and questions for him during a studio visit were of great importance, and led Boisjoly to produce an iconic early body of work titled Makeshift (2010–12). In it, 125 printed, coloured ink-jet papers are taped and overlaid to form a running text that reads as a record of developing thoughts on a state of makeshift being. The work is an enactment of the trust he found at Banff. He asks viewers to enter his knotted language and take it on their own terms.

Another key moment in Boisjoly’s career was meeting San Francisco artist Arnold Kemp in 2013. The meeting was the result of a studio visit from the jury for the Brink award—a biannual prize awarded to emerging artists in BC, Oregon and Washington by the University of Washington’s Henry Art Gallery. Kemp first came to prominence in 2001 with his participation in “Freestyle,” the Studio Museum in Harlem’s post-black art survey exhibition. Touted as a member of a generation undoing their status of being black artists, Kemp’s concerns are echoed by Boisjoly’s own ambitions to undo some of the structures that process his work through the filter of Indigenous art.

Boisjoly’s series an other cosmos (2012) addresses this ambition. Produced for the Vancouver Art Gallery’s 2012 exhibition “Beat Nation: Art, Hip Hop and Aboriginal Culture,” the work shows Hubble Space Telescope images overlaid to form conventionalized Northwest Coast Indigenous imagery with iconic ovoids, U-forms and S-forms. The work is motivated by the album art and mythology of Parliament Funkadelic, a band known for radical lyrics, theatrical live performances and engaging Afrofuturist notions of black space travel as a way to speak of the optimistic potentials of post-identity politics. Through this association, Boisjoly is critically propelling his own ambition to move beyond being firstly filtered as Indigenous, and then secondly as an artist.

With a similar post-identity disquiet at play in his work, Duane Linklater, the Sobey Art Award–winning artist from North Bay, has long been in conversation with Boisjoly about the conditions that he and many other artists of Indigenous identity share. They discuss the subject over meals in Vancouver, through Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, and, in the context of Calgary’s Esker Foundation exhibition “Fiction/Non-fiction” in 2013, at public academic talks. Central to the dialogue are questions about who the work is made for. For Boisjoly, the fact of the matter is that, more often than not, it is a non-Indigenous audience that views his and Linklater’s work. These terms of reception beget a larger question about Indigenous contemporary art. If the consumption of the work happens mostly outside of Indigenous contexts, is the work Indigenous in its experience?

Linklater and Boisjoly explore the movement of the Indigenous context in their work. Linklater’s installation Learning, first installed at Susan Hobbs Gallery in Toronto in 2013, incorporated branding of the Ontario Northland Railway company as part of a large-scale wall painting. The railroad company was controversially privatized and downsized, despite its essential service of connecting rural and Indigenous communities to urban centres in Southern Ontario. In the work, Linklater locates the Indigenous as something that is in both an engaged and withdrawn position, welcoming a back-and-forth flow between Indigenous and non-Indigenous contexts. The ability to act in multiple spaces is paramount; any limiting of this drive is damaging.

Boisjoly’s photographic series (And) Other Echoes (2013), first exhibited at Simon Fraser University Art Gallery in Burnaby, presents a collection of dark tonal images framed behind thick, tinted Plexiglas, which are the result of placing an iPad on a flatbed scanner while it played scenes from the 1961 film The Exiles. Directed by Kent MacKenzie, the film follows a group of Native Americans from dusk until dawn in Los Angeles. They speak candidly about home, community and the future. Boisjoly transforms the moving images into still images. He captures the media in motion and solidifies the pixels. Wavy buckles pattern the images with gradient hues that ripple along its surface. The cuts between scenes fuse in a single frame as a result of the time it takes for the image sensor in the scanner to travel across the surface of the video screen. When one views the works alongside each other, it becomes clear that both Linklater and Boisjoly are influenced by their ongoing relationship. Their practices speak of a state of continual becoming. They make critically charged work that skirts one’s grasp while being grounded in material reality.

In 2014, Boisjoly travelled with his wife and daughter to spend six weeks at the Banff Centre in the Indigenous thematic-residency program “In Kind” Negotiations. It was his fifth visit to Banff, and this time he was leader instead of participant. Boisjoly designed the program and invited guest faculty members, including Arnold Kemp and Joar Nango, a Sámi artist based in Norway. Together they welcomed 10 international artists of different Indigenous identities to work through Boisjoly’s notion that “there is no particular way things are supposed to have been,” an open-ended framework to discuss post-colonialism. Much of the discourse revolved around undeclared or partially declared intentions—a method of not saying directly. Yet the tone was aspirational in framing a parallel reality where things might have gone differently. By facing up to the elephant in the room, Boisjoly made space for the participants to locate themselves within a post-identity spectrum of engagement that lay somewhere between the Indigenous and the global. It was at this time that Boisjoly connected with French curator Céline Kopp, director of artist-run space Triangle France in Marseille, who invited Boisjoly to take part in the centre’s 20th-anniversary project, “Moucharabieh,” in February 2015.

Engagement is what Boisjoly asks of his audience and students. This fall, Boisjoly joins Emily Carr as an assistant professor. Influential Indigenous scholar and curator Richard Hill will begin tenure as Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Studies/Social Practice at the school. Hill, known for exhibitions such as “World Upside Down” (2006) at the Walter Phillips Gallery and “Meeting Ground” (2003) at the Art Gallery of Ontario, brings critical agency toward Indigenous cultural studies. Boisjoly is planning a new thematic course for senior students, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, that will remind them that it is their responsibility to deal with not only their identities and histories, but also the making of work that travels further afield and connects with complementary views.

The impetus to teach relates to Boisjoly’s most recent solo exhibition at Vox in Montreal this past spring. Titled “From age to age, as its shape slowly unravelled…” it included a new photographic series and a video. Boisjoly worked with material from Chris Marker, Alain Resnais and Ghislain Cloquet’s 1953 film Les Statues meurent aussi. At the opening of their film, which structurally associates African art and anthropologically treated objects within museum displays and among their audience, the directors say, “When people die, they enter into history. When statues die, they enter into art. This botany of death is what we call culture.”

For this new series of images, Boisjoly scanned an iPhone screen to capture images of masks, busts and statuary that appear distorted, stretched and dissected in dark space. The images are less about the faces themselves and more about the way they are treated in the original film. They appear similar to the way he treated his images from (And) Other Echoes, however this time the images are not heavily weighted and framed, but rather printed on a self-adhesive vinyl stuck directly to the walls. The gesture ensures that the arrangement of the images is fixed. They are retained in the installation in the way that the artist saw them and related to them. Boisjoly disentangles the complexity of these images by engaging with a trajectory that maps the real being ferried into the ethnographic, then traded as the content of a film, and currently reformed into works of art.

In an essay in London’s Tribune in 1946, George Orwell took on the contradictory politics of the post–Second World War era, writing, “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” Boisjoly asks viewers to look to their noses and perceive the gaze that lies between themselves and objects. His art is about how seeing develops over time, and about how we are compelled to make something in the way that we see it. It affirms our motivations within that process.

This is an article from the Fall 2015 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, visit its table of contents. And to get each issue of our magazine before it hits newsstands, subscribe now.