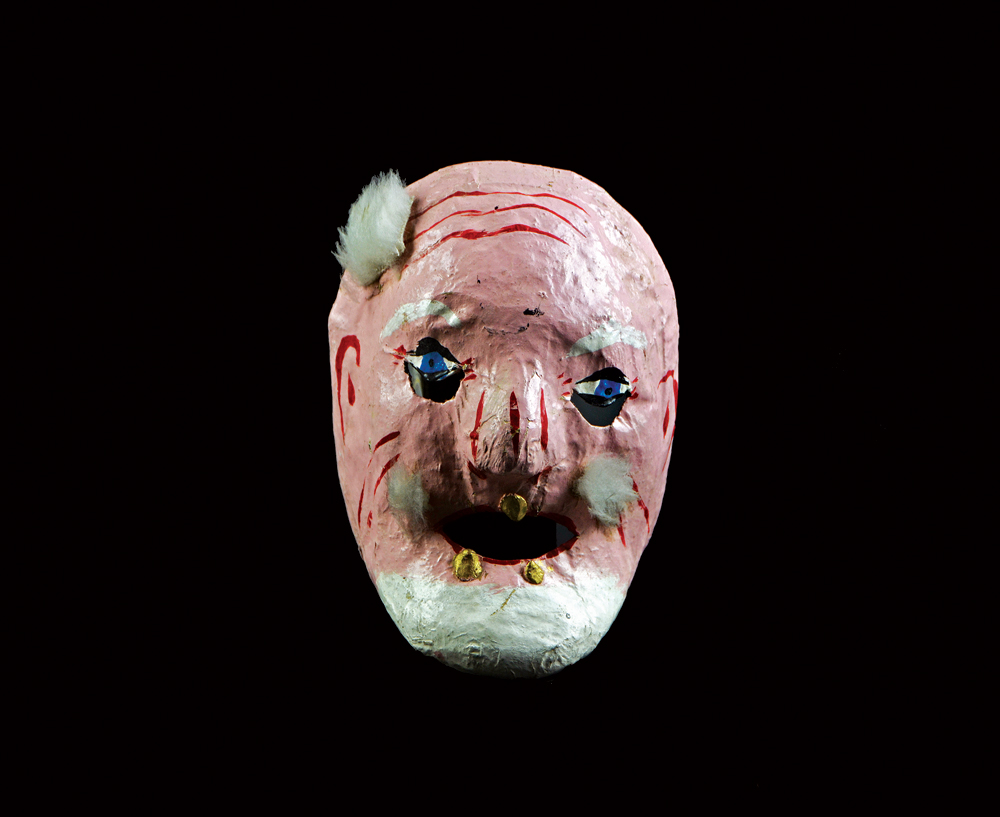

This is how horror stories start. Two brothers buy and renovate an old building in rural Alberta, then fill it with curious collectibles: A plaster death mask from 1850s Holland. A wooden Ouija board from 1940s Baltimore. Ventriloquist dummies. Vodou dolls. Garden gnomes. And not just any gnomes—these are family heirlooms, of a sort. It was Jude and Brendan Griebel’s ancestor Philipp Griebel who invented the iconic ceramic lawn ornaments in the 19th century, whimsical symbols of simpler times in Germany (with an admittedly kitschier pedigree this side of the Atlantic).

“One of them’s got a liquor bottle; the other is playing an accordion and has these disturbingly sharp teeth,” says Brendan with a grimace.

“They’re painted and put together by hand,” adds Jude. “Art objects, really, even if they’re mass produced.”

This fantastical biographical note is just one of the details that make up the brothers’ journey to their latest venture: the Museum of Fear and Wonder near Bergen, Alberta. The idea crystallized while they were visiting Guanajuato, Mexico’s Museo de las Momias, but really, they’ve been preparing for this project all their lives—and have the storage lockers to prove it.

“We’re not hoarders; we’re discerning collectors,” Brendan says carefully. He is an Arctic archaeologist mainly based in Cambridge Bay who recently moved to Ottawa to work on the exhibition “Inuinnauyugut” at the Canadian Museum of Nature. Jude is an acclaimed Brooklyn-based artist whose resin sculptures—including anthropomorphized houses and hybrid bodies—explore themes of waste, nature, decay and pollution, and whose most recent exhibitions include “Crafting Ruin” at dc3 Art Projects in Edmonton and Plastic Ghost, an installation in Jyväskylä, Finland. Previously, they worked together on a project at North Carolina’s Elsewhere museum, a series called Yellow House that had them photographing objects through a rotting dollhouse.

The brothers’ interest in oddities was almost a given considering their upbringing. Raised by a conservator mother and a neurosurgeon father with a thing for medical antiques, they regularly travelled the world as a family, including a trip in their teens (they’re now in their 30s) that took them to Europe, Asia and Polynesia. Yet while many of the objects they’ve collected come from far-flung places—a Namibian divination basket, a Tibetan kapala (skullcap)—the museum itself is pure Prairie Gothic. The structure (which Brendan is currently filling with antique display cabinets from shuttered butchers, candy shops and the Hudson’s Bay Company) formerly served as army barracks and, at one point, part of a German internment camp.

“The tales and fears of the Prairies come from isolation, harsh winters, how light affects your day…” muses Jude, citing the drawings of Marcel Dzama and films of Guy Maddin when he recalls their childhood. He describes traditional crafts tailored to the seasons, games staged in abandoned houses, pranks played in the cornfields, and the road trips of their youth, days of driving broken up by small-town attractions.

“Anywhere with the Biggest Anything,” summarizes Brendan. “Places that would lure you in.”

“They’re the last pockets of folk mythology left over from an old world,” says Jude. “And sometimes they say more about a place than any formal government archives.”

According to the Alberta Museums Project, the province is home to more than 300 museums, most of them in rural areas. Add to them roadside attractions, and a local road trip could hit everything from Glendon’s Giant Perogy to St. Paul’s UFO Landing Pad to the Torrington Gopher Hole Museum, where taxidermy rodents are dressed up and posed in bucolic scenes: playing hockey, slow dancing, building snowmen.

In 2017, niche museums are remarkable for their continued existence as much as their actual collections, and this long-faded glory is apparent in the Griebels’ most recent acquisition: a gang of famous villains from a defunct wax museum in Niagara Falls. Jude and Brendan list off the figures they nabbed (Lizzie Borden, Ted Bundy)—“We chose them based on notoriety and quality,” explains Jude—and kick themselves over the ones they missed (Charles Manson, John Wayne Gacy). They speak with the glee of kids swapping baseball cards, and yet, it’s in this discussion that they out themselves as anything but exploitative showmen or ironic gore hounds. Despite the quirky, even gruesome, subject matter they’ve taken on, they are tactful, even sensitive, when it comes to this project.

“The guy who sold them to us knew how much they meant to kids, growing up. He didn’t want to just get rid of them all on eBay,” says Jude, before pointing out that most of the wax figures were made in the 1960s, by real craftspeople, before Niagara achieved full tourist-trap status. He explains how the art form arose from the need for medical models during the Enlightenment, when real cadavers got too expensive, weaving in the tale of Louis Auzoux, a medical doctor who revolutionized the field again with papier mâché—antecedents of the classic “dissectible” anatomical models still popular today. Auzoux learned his craft from makers of children’s dolls in 19th-century Paris. “You see the same technique used with two radically different emotional understandings of the human body,” says Jude. (Unsurprisingly, the Museum of Fear and Wonder showcases many baby dolls and children’s toys worthy of Mexico’s infamous Isla de las Muñecas, or Island of the Dolls.)

When it comes to the wax figures they’ve bought, the brothers are adamant about one thing: “The point is not to make a novelty museum,” says Jude. And so the villains won’t be displayed in blood-spattered dioramas, but instead have been stripped of their costumes, down to their carved limbs and stuffed torsos. In short, says Jude, “We’ve removed the dramatics.”

They’re also not planning on any bold, P. T. Barnum–style ad campaigns or flashing arrows to coax Calgarians to undertake the 90-minute drive to the museum. In fact, most of the brothers’ sales tactics would make the humbug-happy showman roll in his grave. They only plan to open for three months in the summer (with an artist- or writer-in-residence acting as a didact), won’t be charging admission and have no plans for a gift shop. And while the museum does have a website and Instagram account, they only offer a few pictures of select objects shot against plain backgrounds—an Inuit shaman belt, two mating flies trapped in amber—and glimpses of the space itself. “We don’t want that many people to come,” Jude admits, with a laugh. It’s not that they’re being difficult, but that they’ve discovered something important after years of going off the beaten path to museums in people’s homes and private spaces, from a human hair collection in Turkey to an erotica museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, that was also a working VD clinic: the journey itself is part of the experience.

“Time is the biggest investment you can make now, and moving through that physical space,” says Brendan. “If people are interested enough to come and see it, if it’s remote, that’s already part of it.”

Jude cites the Museum of Jurassic Technology as an influence in its approach to marketing as much as content, in that most of its popularity has been organic, and its converted Culver City storefront—showcasing microminiatures and portraits of Soviet space dogs—is available to both those who’ve made the pilgrimage and curious passersby. “It was intended for random strangers to step into,” he says.

Jude also recently met about 40 kindred spirits at a niche collectors’ conference in New York, attendees with the sorts of interests that make medical dummies look mainstream: a woman who gathers and mounts the miniscule tires from toy tractors; a couple that’s built a tribute to Tonya Harding and Nancy Kerrigan in their Brooklyn apartment; and Marion Duckworth, a septuagenarian whose collections live alongside her—playbills, skeleton keys, Snow White figurines—in a 1600s Dutch farmhouse, the oldest inhabited home in the city, complete with a graveyard. When asked where his interests lie on a spectrum of strangeness, instead of answering, he challenges the question: “I don’t like the word strange, it’s boring. Or the word creepy. I prefer to call the objects we collect emotionally complicated. Or uncomfortable. There are better words than strange to explain the grey area.”

It would be too easy to paint the Brothers Griebel as moustache-twirling eccentrics, but again, where there could be a gotcha there’s simply appreciation. And despite what could be called a resurgence of socially (or social-media) acceptable interest in the occult—the Twin Peaks revival, cyberpaganism, podcasts like My Favorite Murder, the #trypophobia tag, “creepypasta” online urban legends—they’re not set on riding that wave.

“Whatever’s happening with this resurgence of the supernatural, this Internet gothic, we don’t want any part of that,” states Jude. It’s not that he is totally averse to horror as a genre (he admits to a fondness for visceral, pre-CGI special effects in movies like C.H.U.D. and The Dark Crystal), it’s that they are presenting objects in what he calls a “post-material world.” And that is, he says, the biggest difference between his personal work and this project: the former is about creation, the latter about consideration. “We’re trying to highlight objects in the right way. It’s only when they’re looked at as gimmicky that you’re dismissing people’s beliefs. It’s about respecting them and giving them the right space.” It’s this approach that has Brendan and Jude convinced they can transform visitors’ fear into careful reflection. Or even, if they get it right, awe.

This post is adapted from an article in the Fall 2017 issue of Canadian Art. To get each issue of the magazine delivered before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.