Every few weeks, the same scanned news clipping shows up on my social-media feeds: “Wife of the Master Mural Painter Gleefully Dabbles in Works of Art.” It’s from a 1933 copy of the Detroit News, and the wife in question is Frida Kahlo.

Everyone can laugh at (and “Like”) the sexist relic, secure in the knowledge that she’s since been promoted from a mere dabbler to one of the most prominent artists of all time.

This tendency to treat women as footnotes in other people’s lives is hardly ancient history. It’s the motivation behind the Art and Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-thon, and was at the top of my mind as I arrived at Concordia University’s engineering and visual-arts complex in downtown Montreal on March 5, 2016.

The typically daylong event was launched three years ago in New York by art librarian Siân Evans, artist and curator Laurel Ptak, curator Jacqueline Mabey and artist and professor Michael Mandiberg, all intent on filling a digital void: women on Wikipedia. In three years, the edit-a-thons have grown to almost 300 events worldwide, including workshops at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Emily Carr University of Art and Design and the Banff Centre in Canada, and, internationally, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Tate Britain and Paris’s Musée des Archives nationales, among others (including virtual editions).

The goal isn’t simply to create, fix or flesh out pages for overlooked female artists, but to give women the tools to edit Wikipedia. Research from 2011 found that nine per cent of editors self-identified as women and that retention rates for them are lower than for men. Whenever controversies arise—the battle over Nova Scotia teen Rehtaeh Parsons’ page, the migration of female authors to a Women Authors section (with no corresponding move for men)—pundits inquire: “Does Wikipedia have a woman problem?”

While it’s a worthy question (though I’d add: “More than Twitter? More than Facebook?”), my reason for attending was to find out whether it’s women who have a problem with Wikipedia, and to figure out if it’s something they can—or should—fix themselves.

**

“Wikipedia tends to cover certain topics really well. You can probably guess which ones,” says co-founder Mandiberg, dryly, before listing them off. “Anime, the Civil War…” Art is not one of them, historically. As for the page on Feminism, it was the third-most edited topic on Wikipedia in 2001, the site’s first year in existence. (The most-edited: Creationism.)

Add Art to Feminism and the YouTube comments write themselves. Under a fairly innocuous clip covering a Chicago edit-a-thon, the top three commenters predictably manage to: compare feminists to Nazis, accuse organizers of alienating and demonizing men and bravely declare “the simple fact that you think ‘information’ requires a gender aspect to it (a male voice isn’t enough, we must have female voices) gives reason not to take Wikipedia seriously.”

But people do take Wikipedia seriously, all five million–plus articles of it. It is the seventh-most popular site in the world, and the same experts who once called for outright bans are now pushing cautious guidance.

“Really, all sources are inherently biased,” says edit-a-thon co-founder Evans. “Yet we’re all still invested in an idea of an authoritative, neutral point of view. And I’m not sure what alternative there is.”

It’s becoming clear that if you can’t see it, you can’t be it, and if you can’t link to it, you can’t use it to win an argument on Reddit.

**

The Concordia edit-a-thon is taking place, appropriately enough, in the art department’s Digital Image and Slide Collection. The room houses 300,000 slides, from contemporary sculpture back to prehistoric cave paintings, all painstakingly labelled (many by typewriter!) and filed away in massive drawers—but only available to those who know to look for them in the first place.

When I enter, a dozen women and two men, one in a Wikipedia-branded shirt, are turning on laptops. I set up across from Wikimedia Canada vice-president and volunteer Benoit Rochon. As a Quebecer, he understands firsthand the elusiveness of objective wisdom, grappling with his counterparts in France over the credibility of local Montreal sources like La Presse (“They said, ‘It’s not a national paper’”) or the proper term for “hockey puck” en français.

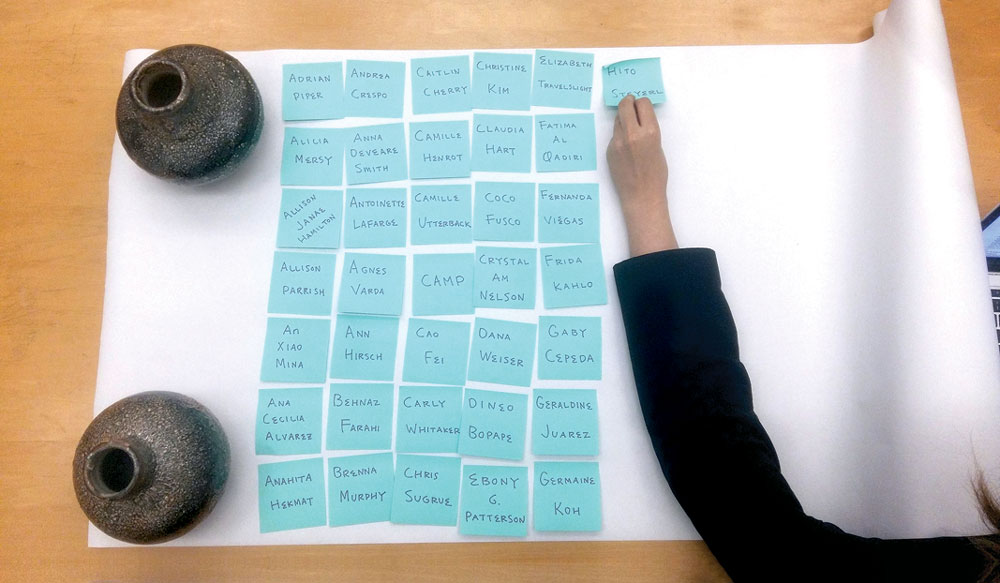

But before typing a single word, we take part in a workshop led by Anne Goldenberg, a French scholar who specializes in online knowledge (her doctoral thesis: “The Negotiation of Contributions in Public Wikis”). We’re not even using computers, yet, just coloured markers and Post-it notes.

We’re making nametags. We’re eating vegan cookies. We’re sharing our preferred pronouns. It’s the safe space your libertarian brother-in-law warned you about.

First, we share what brought us here this Saturday: A PhD candidate came to pay tribute to her favourite artist. A young publishing-house employee wants to fill the void of Latinx knowledge online. A 64-year-old audit student says her professors have all banned the site, so she’s here to “find out what it’s all about.” A Muslim attendee was appalled by the Wikipedia page for World Hijab Day: “It was a mess. I want to help fix that. But I’m kind of terrified.”

The word “terrified” comes up quite a bit for such a small group. Although participants are advised to avoid beginning with controversial pages and to consider gender-neutral usernames to prevent online abuse, attendees’ reluctance seem to be less about inevitable harassment and more about the virtual unknown.

Even Art and Feminism’s Canadian ambassador, Amber Berson, who has been organizing events since 2013, admits to initial anxiety. “I was scared,” she says, “but I figured, let’s be scared together.”

She speculates that one source of trepidation is a perceived lack of community—to the uninitiated, all Wikipedia’s online interactions can feel like they’re with bots, not humans. And even with the user-friendly editing buttons, the layout can feel about as inviting as Apple Terms and Conditions, more hieroglyphs than literature.

Another potential deterrent: seeing hard work erased in an instant, with cryptic or curt feedback like “tagging for speedy deletion” and “significance not asserted.” A legitimate deletion (say, for plagiarism or inadequate citations) can feel like a personal slight, especially if you’re used to having your contributions rejected offline. While Wikimedia has introduced initiatives like the Teahouse, an informal online community for newbies, the warmth of face-to-face interaction—even when someone is telling you you’ve made a mistake—is another point in the edit-a-thon’s favour. In the words of one attendee, “I just want to learn from someone who’s not going to yell or talk at me.”

**

“We are all biased,” Goldenberg stresses, but in her French lilt it sounds less an accusation, more an opportunity for introspection. She even makes it a game, reading aloud from her photocopied adaptation of the Anti-Oppression Toolkit:

“Add a point if your family had more than 50 books in the house when you were growing up.”

“Subtract a point if you have ever been unable to attend an event or gathering because it was not accessible to people with your disability.”

“Add a point if you studied the history of your own ethnic ancestors in elementary school.”

Without stating it outright, she’s breaking down the assumptions in Wikipedia’s mission statement—“The free encyclopedia that anyone can edit”—revealing what resources are really needed to write an article, beyond a solid bibliography.

Leisure time, Internet access, confidence, safety. Editing is a cost-benefit analysis: If most women can expect a second shift of childcare and domestic labour, what energy is left for the “digital shift” of Internet use? And why spend it formatting text or arguing instead of playing cat-collecting video game Neko Atsume?

A gendered confidence gap is another potential hurdle, and one that’s even harder to quantify. As in the offline world, the myth of meritocracy is essential to maintaining the status quo: If female artists don’t have their own entries, it’s because they don’t deserve them; if women don’t edit, it’s because they aren’t interested or skilled enough.

Canadian filmmaker and activist Astra Taylor eviscerates the dream of an open Internet quite thoroughly in her book The People’s Platform, where she quotes a study by Northwestern University’s Eszter Hargittai measuring the online competence of male and female users. Despite being equally capable, “Not a single woman among all our female study subjects called herself an ‘expert’ user…while not a single male ranked himself as a complete novice or ‘not at all skilled.’” (To paraphrase Toronto writer Sarah Hagi: Lord, give them the confidence of mediocre white men.)

Even an esteemed Wikipedia editor, the late Adrianne Wadewitz, told PBS that when she revealed her gender after working anonymously: “There was a lot more skepticism. And a lotta times when I made arguments…I was accused of being hysterical or emotional. Things that had never happened before.”

Could it be that the same congenital gift that allows men to host exhibitions celebrating women in the arts while showing a majority of male artists (see: Pharrell Williams’s 2014 show “G I R L” at Galerie Perrotin), and to hold panels on diversity without actually seeking out diverse viewpoints (see: the Tumblr Congrats! You Have an All-Male Panel), makes them the natural wardens of Wikipedia’s hallowed Neutral Point of View? Is mansplaining a must for Wikipedia editors?

(Add a point if you are a man.)

**

Despite funding for catering and childcare, Goldenberg stresses that even today’s event can’t escape criticism. Just as game designer Veve Jaffa notes in tech-and-culture journal Model View Culture: “As corporations vie for token representations of inclusion, the presence of marginalized people at publicized events portrays a public image of progress, even though no real resources are moved in our direction.”

One participant suggests Berson try to find co-organizers from underrepresented groups. Another wonders if the venue itself is a barrier. Though the school setting seems welcoming—it’s close to the metro, has handicapped washrooms, there’s even a feminist portrait series by Marisa Portolese in the gallery downstairs—she says it could be intimidating to people in her community who aren’t used to navigating academia. (Add a point if you grew up assuming your family would pay for your education.)

Berson suggests that the edit-a-thon’s hidden strength may lie in how it’s marketed: Rather than asking, it should offer. The comfort and confidence that comes with editing Wikipedia can translate into learning other skills, like designing websites and learning code.

“Don’t forget, you could also use that free labour on Facebook,” reasons co-founder Mabey, “but then it becomes the intellectual property of Mark Zuckerberg.”

The event is also a chance for activists to see the fruits of their labour in a tangible (albeit potentially erasable) way—a rarity in a sea of diversity initiatives and awareness campaigns. For once, the word “empowerment” actually seems appropriate.

“I really like that feeling of power,” reveals Magdalena Olszanowski, her eyes lighting up. “Of knowing someone’s going to Google something and find what I made.”

Olszanowski, an artist, documentary filmmaker and teacher, already knows how to edit Wikipedia, so she’s skipped the training session this year and is instead nursing her six-week-old while helping her friend, photographer Francesca Tallone, navigate the site. Olszanowski is the first attendee to admit to a motive for editing beyond altruism. She’s finishing work on a movie about women in the electronic-music industry, so she’s adding entries—like Mileece Petre, who creates music from plants’ electromagnetic emissions—with her own documentary as a credible source. (What makes a “credible source” is another big topic of the day.)

At the same time, Olszanowski confesses that when she’s not working on a project, she’s just an average, passive Wikipedia user, not out to give a voice to the voiceless.

“If I look up someone and they don’t have a page, it kind of throws me off,” she says. “But I won’t fix it, I’ll move on.”

She instructs Tallone to look up a name from the artworld: Isabel Bader. She’s redirected to the page of Alfred Bader, Isabel’s husband. Though they are both major philanthropists and have been awarded doctorates, Isabel remains a mere mention on Alfred’s page.

Because really, despite encouraging results—this event produced about 2,000 new pages and 1,500 edits worldwide—this isn’t just a numbers game. In the paper “It’s a Man’s Wikipedia? Assessing Gender Inequality in an Online Encyclopedia,” presented at the 2015 International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, the authors argue that while women aren’t necessarily underrepresented on Wikipedia (overall—they didn’t look at female artists), their entries suffer from structural and lexical bias. While men’s pages tend not to note that they are male, women’s highlight their gender and relationships—an article that mentions a person is divorced is 4.4 times more likely to be about a woman than a man—and tend to link to the pages of men, without corresponding links back.

With a list of female artists in hand, I open my laptop wondering what I’ll find: red links, article stubs or nothing at all. I type in the first name, Baroness Else von Freytag-Loringhoven, a Dadaist, poet and the possible brains behind Duchamp’s Fountain, and am pleasantly surprised to find her listing is comprehensive, even thoughtful. But before I move on, I click through to the page’s edit history, right back to the very first entry. And there it is. What once made the baroness notable:

Else von Freytag-Loringhoven was born in Swinoujscie, Poland…to a German father and Polish mother. Her father, who was a mason, abused Else in her childhood, which led her life to prostitution, venereal disease and numerous affairs. For a while she was an art student in Munich, before marrying in 1901 to a Berlin-based architect.

Abuse, sex work, VD, infidelity. And yet, and yet: 160-plus edits later, a fuller picture of her life has emerged. One that can continue to grow.

Eve Thomas is a writer, editor and artist based in Montreal. This is her article from the Summer 2016 issue of Canadian Art. To get each issue of our magazine delivered to your door before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.

Organizing at an Art and Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-thon in Los Angeles in March 2016.

Organizing at an Art and Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-thon in Los Angeles in March 2016.