Note from the editor: From time to time, we delve into the Canadian Art archives, which stretch back to 1984, to highlight articles of interest to today’s readers. Given the recent passing of iconic Canadian artist Alex Colville, it seemed an auspicious moment to revisit our cover story on him from our Fall 1987 issue. Originally titled “Nothing Phoney” and written by Hans Werner, the article conjures a decade when Colville came in for no small amount of criticism, and also received fresh examinations of his work as a war artist.

If you ever find yourself sitting in Alex Colville’s living room, you may just find his dog Minnow flopped across your lap, chewing on your pen and trying to make your notes for you. Colville comes to take her more than once, and you notice that he doesn’t just pick her up, he cradles her. This doesn’t seem like the man who has been described as austerely aloof as a bank president or a senior executive.

Or worse. In his dismissive review of the 1983 Alex Colville retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Globe and Mail’s art critic John Bentley Mays made this statement: “… like many other mediocre art works similarly wrought with time-consuming care and obsessive attention, these paintings invite a certain kind of admiration—the kind we willingly accord a painting of the Last Supper on a thumbtack, or the precisionist kitsch of Salvador Dali.” But his fit of pique was typical of much art world resentment that came in the wake of the retrospective organized by David Burnett for the Art Gallery of Ontario, resentment against the man who German art critic Heinz Ohff declared “the most prominent realist painter in the Western world.”

Richard Perry’s 1985 article in the Canadian Forum, entitled “Alex Colville: Why Have We Made Him Head Boy of Canadian Painters?” follows in the same footsteps. While it makes a couple of good points and raises a few interesting questions, it is difficult to take seriously for the spitefulness that animates it. An attempt to make Colville’s art bear the entire burden of a specious political theory about the Canadian character, managing along the way to imply that Colville is dishonest, self-righteous, and hung up on power, authority and money, this piece succeeds mainly in recalling George Orwell’s words about all the smelly little orthodoxies of our day.

More recently, in a 1986 exhibition at the Carmen Lamanna Gallery in Toronto, this resentment was manifested again in John Scott’s unflattering cartoon of Colville minus a jaw (with a snapshot-size photograph of Colville’s wedding stuck to its surface), flanked on one side by a reproduction of one of the drawings from his war diaries. The work may remind you that headhunters used to remove the lower jaws of their victims as a sign of contempt. But while this show purported to be a comment on war artists, it mostly made you wonder if Scott had ever talked to any veterans. Moral indignation is easy to come by.

These attacks have little of substance to say about Colville’s art and a lot about his character, his politics, or even what is imputed to his psyche. The sources of such resentment are pretty obvious. Colville has offended against all the little orthodoxies of the academy. He has had no use for contemporary art and has totally ignored it; he has kept himself apart from other artists and ignored them too; he owes nothing whatever to the hothouse politics of the Toronto art scene, and has remained steadfastly conservative and therefore politically incorrect. Worse, he has gained an unassailable international reputation when he should have remained a quaint Maritime regionalist. And, to top it off, he’s become a rousing commercial success, his works currently commanding prices in the $100,000 range.

Resentment, of course, is more conveniently sustained when focused on a stereotype uncontaminated by reality; the stereotypical image of Colville seems to be that of an austerely aloof reactionary establishment lackey whom Perry accuses of emotional sterility, and Scott seems to imply is involved in some sort of conspiracy of silence about the horrors of war. What all this fails to acknowledge is the reality of Colville’s experience (chiefly the war), and the depth of his personal philosophy (inspired by existentialism). To understand Colville, we must go back to his war art.

The first thing that strikes you as you enter the modest exhibition “Alex Colville: Images of War” — on view through December 31 at the Canadian War Museum, Ottawa—is that the oil paintings, worked up from earlier field studies, are more moving than any reproduction could ever hope to be. The images of the ordinary day-to-day life of soldiers leave Colville open to the imputation of being shy of the horrors of war, but a look at his war diaries reveals that on more than one occasion Lieutenant Colville actually got himself taken on battle manoeuvres because he felt compelled to share all aspects of a soldier’s life (which was a minor bit of insubordination, since war artists were supposed to stay clear of immediate danger).

His choice of subject is a matter of temperament, not squeamishness. Contrasting his own war art to Goya’s Third of May and The Disasters of War—works that he admires greatly—Colville says it’s not in his nature to do explosive work: “You couldn’t imagine Renoir doing a crucifixion.” And yet, in reflecting his admiration for the resilience of ordinary men, the quiet beauty of Colville’s war art achieves something more subtle than any lurid depiction of horror: it shares the profound sorrow of those who actually went and faced it.

Colville’s comment on his 1944 painting Nijmegen Salient is revealing in this respect as well as for what it reveals of his philosophy. The painting’s steely greys and leaden browns precipitate the viewer into an atmosphere of mud, dampness and chill, in the midst of which, dwarfed by the barren and clammy soil, a solitary soldier sits cleaning a Bren gun. In an earlier drawing that probably depicts the scene as Colville actually saw it, a second soldier is emerging from the dugout and the foreground is left open with only a rifle to balance the composition. In the painting the second figure is taken out, which contributes to the remaining figure’s isolation. The rifle is replaced by a barren, fallen tree that sweeps across the foreground plane, emphasizing our distance from the subject, and frames the lone soldier along with a broken-down motorbike, empty gasoline canisters, crates, and a couple of stripped American gliders on the horizon. Painted when Colville was only 24, this is a poignant image of a noble, if bleak solitude. “But,” Colville is quick to add, “he’s handling it.” War is a situation where you go on living or go berserk.

And so, from an existentialist point of view, is life. “I can’t go on, I’ll go on,” as Samuel Beckett put it. Nijmegen Salient can be seen as an image of man as described by the 17th-century French philosopher Blaise Pascal: the thinking reed in an alien universe. Pascal is usually considered a precursor of the existentialist philosophy that archieved prominence in the post-war period, through the writings of Sartre and Camus, and that Colville, together with his friend (and now pre-eminent Canadian philosopher) George Grant, turned to at the time.

It may seem off that a man who calls himself a Red Tory should espouse a philosophy that was embraced by a younger generation as subversive. But whether you go along with Ivan Karamazov or say, if God does not exist then “all is permitted,” or have already seen what happens when all is permitted and therefore commit yourself to carving order out of an alien universe, nobility consists in preserving your integrity and in accepting the consequences of your choices. If you look at Colville’s 1945 Tragic Landscape, in which a dead German paratrooper lies abandoned on the road to Deventer, Holland, as a cow turns away to more important preoccupations, you get the picture. Here, there is no moral universe to appeal to. Like the cow, the universe doesn’t care.

And neither does God. In Night, Elie Wiesel describes the hanging of an 11-year-old boy in Buna concentration camp. One of the more elderly inmates cries out, “Where is God?” and is answered by another who says, “He is hanging here.” Colville saw what remained of the corpses of god when, at the age of 24, he was sent as a war artist into Bergen-Belsen concentration camp a few days after it was liberated. He’ll tell you how he made sure that he and his driver (who liked his drink) didn’t take any liquor with them because he figured the situation could get a little “iffy”. Press him further, and he’ll remember seeing a couple of British soldiers carrying a female survivor out of the camp barracks, slung in a blanket. “The vulnerability of a naked female body in this context seems bizarre,” he says, and you sense a seismic disturbance in his voice. But he won’t get emotional about it. Instead he cites J.D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey: nothing phoney.

These experiences left him with an indelible image of mankind’s capacity for evil, an apprehension that was borne in on him all the more forcibly when a 1971 invitation to Berlin gave him the opportunity to lay to rest his ambivalent feelings toward Germans. He discovered that they were no more evil than anyone else. “Germans just had the misfortune of finding out sooner than the rest of us how bad humans can be.” Which does not make Colville a misanthrope. It means he does not share the liberal faith in the perfectibility of man, or the shallow optimism you get when you just add sociology and stir.

Belsen showed Colville what happens when all hell breaks loose, and because we live in a precarious and inescapable proximity to this hell, the most we can do is strive to contain it. And that takes power. The graphic symbol of power is the gun, Colville tells you, and goes on to quote Malcolm X: “On stick-ups I used a .38 and noticed that people talked different when they were looking into that little black hole.” In Colville’s 1980 self-portrait Target Pistol and Man, the viewer is placed in just this unhappy position. Possibly Colville was feeling an echo of Malcolm X’s words as he was painting that image, but it’s highly unlikely that he was planning a hold-up. More likely the picture resonates with the memory of Colville’s first night in Belsen when he slept like a log because he kept a Browning automatic under his pillow as a talisman against the chaotic conditions of a Germany in total collapse. Power can be evil, but it also protects the weak. The figure of justice, he’ll remind you, carries a sword in one hand. The use of power, he says, is a key moral and philosophical problem, and that’s what his paintings featuring pistols are about. Power is a condition of life: a thing that must be handled.

Existentialism not only helped Colville make sense out of his war experience (which he says he badly needed to do), but its philosophy of leanness also informed his technique. The breakthrough came with Nude and Dummy in 1950, when his expression was compressed down to “the minimalist thing”, which allowed him to discard everything that could go. As he puts it, “What’s left you’re sure of, at least you hope you are.”

The precision and austerity that came of Colville’s philosophical preoccupations has an effect on the viewer that propels Colville’s images beyond the anecdotal and into the realm of icon. His carefully constructed images seem to bend time and space around themselves and, for that brief moment observed by the artist, each scene constitutes an entire universe unto itself. Closed. And private. In the same way, the positions of his subjects, with their faces averted and their backs turned to the viewer, avoid any narrative engagement, remaining inviolate on some plane other than that of normally experienced time. In this, Colville’s paintings achieve something of the noble monumentality of the Egyptian art the artist came across in the Louvre in 1945, in which he saw the fleeting made eternal.

In the pictorial arts, Colville once said, space is a metaphor for time, and the starting point of Colville’s work is normally a formal problem of spatial relationships, whether posed by reclining figures or a taxi about to sweep down a hill in Hong Kong. Or, as in Dog and Priest (1978), as a device for giving a priest the head of a dog. But in spite of their clearly articulated spatial composition, you can’t help noticing that the figures in these paintings don’t really appear to be touching anything. Although this is due to the absence of cast shadows (one of the things Colville found he could do without), the effect is one of volume without mass. One gets the feeling that it is only Colville’s renowned rigid geometry that pins his world in place, leaving you with the unsettling sensation that — in words Colville is fond of citing as an admirable instance of the German sensibility — things could go to hell in a minute. In Colville’s work time is frozen in space, but the viewer is haunted by the knowledge of thaw and dissolution. “Space,” as French philosopher Gaston Bachelard has written, “is our friend, but time has death in it.”

Colville describes himself as having an enhanced consciousness of the fleetingness of life. And little wonder. At the age of nine he was stricken with a bout of pneumonia. The outcome, in an era when there was no effective treatment, could easily have been death. Possibly his later war experience took him back there. But like many who have been near death, and like many veterans, Colville values deeply the simple things in life. Cyclist and Crow (1981), in which a woman skims along on a 10-speed preceded by a crow scudding across the fields, evokes the sensation of high speed swept up into the stillness of absolute space, capturing the intense clarity of pure perception before it collapses back into time. It might as well stand as a vision of the beautiful, which George Grant has defined as an image of perfection and the good. Of Colville it might be said that perfection is the discipline of his technique, and of his life. The good is the commonplace.

Colville’s art reveals a man creating a sense of order in an alien universe. At the centre of his world is his wife, Rhoda. She is the model for the most of the women (and all of the nudes) in his paintings and, as in Low Tide (1987), frequently appears large in the foreground with a truncated male (often the artist himself) appearing as a marginal element in the background, although Refrigerator (1977) shows them on an equal plane in an intimate scene of a couple raiding the fridge at night. This is Adam and Eve, and their intimacy is Eden.

In these images of women, however, you experience another level of his art; the enigmatic. The longer you stare at Low Tide, to take one example, the more this apparently ordinary image begins to nudge you into the feeling that you may be contemplating the Jungian archetype of the Great Mother, especially as in Colville’s paintings women are usually depicted in, on, or near the natural element that is the archetypal symbol of the feminine and of the subconscious: water. According to Jungian theory, such images touch upon the realm of the inaccessible. No wonder, then, that in these paintings the male seems to be an outsider, even in Couple on Beach (1957), in which the male is in the foreground.

Jungians say that archetypes arise from the unconscious. They are dangerous, and must be treated with respect: distance. You cannot look them in the face. These are, of course, all recognizable qualities of Colville’s art. Like archetypes, his paintings work on us with the insidious potency of unconscious contents, and persist in our minds like uncanny after-images. They resist the feeble attempts of the conscious mind to defuse their power through definition. It may be for this reason that some of Colville’s critics have claimed that his paintings are unintelligible to the point of meaninglessness. Like archetypes, Colville’s images inhabit a silence that must be experienced, and cannot be explained away.

Colville has always said that the ideas for his paintings come from the unconscious. Intuitively sensing that he’s on to something important, but not knowing what, his only conscious intent is to make the image concrete to the fullest extent of his rigorous technique. While in Dog and Priest, for instance, he is not unaware of having created an image that may remind you of Anubis, the jackal-headed god of the Egyptians, the painting is to him a somewhat less portentous image of a priest experiencing life through a dog, and a dog experiencing what it’s like to be a priest (all of which grew out of an ordinary enough incident some 25 years prior to making the painting when Colville saw a priest in New Brunswick whose communion with a pet dog and cat he very much admired). Colville works with an innocence that is perhaps not unlike the state of grace that he ascribes to animals, and that allows the images to emerge, as through a medium, without conscious comment.

When our interview is over, and thinking perhaps of Colville’s frequent avowal that he’d like to be a dog, I tell him there’s something about him and his work that reminds me of the animals that inhabit the woods where I live. If you want to see them, you have to pretend you’re not looking; if you want them to stay, you have to pretend you’re not there. Colville, laughing heartily, tells me he’s flattered.

This is a feature article from the Fall 1987 issue of Canadian Art.

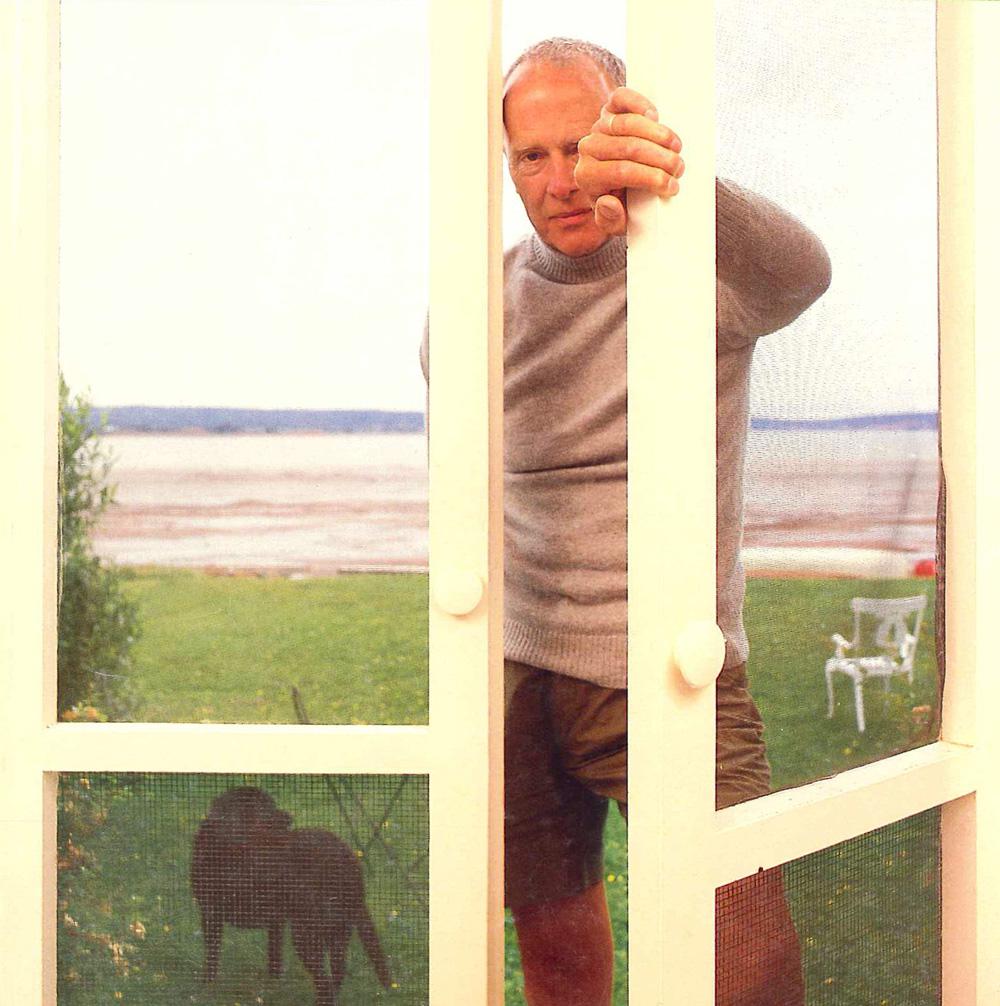

Photo of Alex Colville at his home in Wolfville from the cover of the Fall 1987 issue of Canadian Art / photo John Bladen Bentley

Photo of Alex Colville at his home in Wolfville from the cover of the Fall 1987 issue of Canadian Art / photo John Bladen Bentley