At 82 years of age, photographer Fred Herzog doesn’t move quite as quickly as he used to. But then, few people ever did. In his younger days, Herzog was the kind of guy who’d jump on his Norton motorcycle after lunch and ride back roads to the top of Mount Baker, 180 kilometres south in Washington state, then motor home in time for supper. “Not always at the speed limit,” he says now, with a sly smile.

When he wasn’t making a literal blur across the landscape—and when he wasn’t working full time as a medical photographer at the University of British Columbia (UBC) or raising his family—he shot pictures on the streets. And rather a lot of pictures, we now know, as a result of a series of high-profile solo shows in Vancouver, Toronto, Ottawa, New York and Berlin over the course of just the past five years. Asked to estimate the total number of pictures he’s taken in his life, Herzog will admit to more than 85,000. Of course, those are only the ones he’s kept.

“I suppose I’m a bit of a workaholic,” he says, with a self-deprecating chuckling and a glint of mischief in his eyes. But then, immediately, he’s back to scanning the world around him. “Here,” he says, voice low. “Let’s look up this alley. There are often things here.”

We’re in Strathcona, Vancouver’s oldest residential neighbourhood, just east of the downtown core. I’m observing a crucial part of the Herzog methodology, what his photographer friend Christos Dikeakos describes as his “Socratic walks”: long ambles through the city, camera in hand, by which an inquiry into the world is facilitated. Strathcona might be thought of as Herzog’s most fertile ground, though that runs the risk of overlooking the fact that he’s walked and shot pictures in almost 40 countries around the world and more cities than he can name. It’s a favourite, in any case, a place where he has stalked the streets and alleys for more than 55 years, returning so often that if you’re lucky enough to accompany him and watch him working, you’ll occasionally catch Herzog wondering aloud as he frames a shot whether he might possibly have taken the same picture before. Then he’ll shrug and take it anyway.

Now, he crouches a little, squinting, the small Lumix digital with the Leica lens held almost unconsciously at his hip, like an organic extension of his fingertips. “You see?” he says. “You could do something with that house. And the big pile of superfluous furniture! Yes.… I’m going to take that picture.”

Then he looks eastward to the end of the alley, to the bank of trees there and the dropping sun beyond. He gauges light. He fingers the camera’s manual controls, then swivels and holds the Lumix out at arm’s length, aiming over the fence at a picaresque pile of mattresses and spent sofa cushions stacked in the furrowed backyard, a distressed house beyond, bleached-out boards and peeling asphalt roof shingles. No human form present, but everywhere the fingerprints of man, the hand of humanity, the city alive and breathing, offering up its endless content.

The shutter winks, once. The camera emits a tone. Herzog straightens with a half smile and off he goes. “That might be a picture,” he muses, walking again. “Maybe not a great one. But it’s a picture. And I don’t want to go home empty-handed.”

I’m still looking at the house. Herzog is now 10 metres down the alley. There’s a building around the corner that used to be a convenience store. He wants to show me something there: faded, silvering images of Coke bottles printed onto glass panels above the building’s entrance. He’s been shooting them for decades—30 years at least, he guesses. Each time he returns, they’ve faded a little more, leaching a bit of themselves into the Strathcona air.

When I catch up to him, Herzog is in place already, lens trained upward.

“You see?” he says. “Degraded, but never so much that they don’t have value.”

I watch over his shoulder as another image is made. I’ve never noticed the Coke bottles previously. But now, as the light deepens in tone, as the shadows begin to pool, I know exactly what he means.

Fred Herzog Boys on Shed 1962 Courtesy Equinox Gallery

Fred Herzog Boys on Shed 1962 Courtesy Equinox Gallery

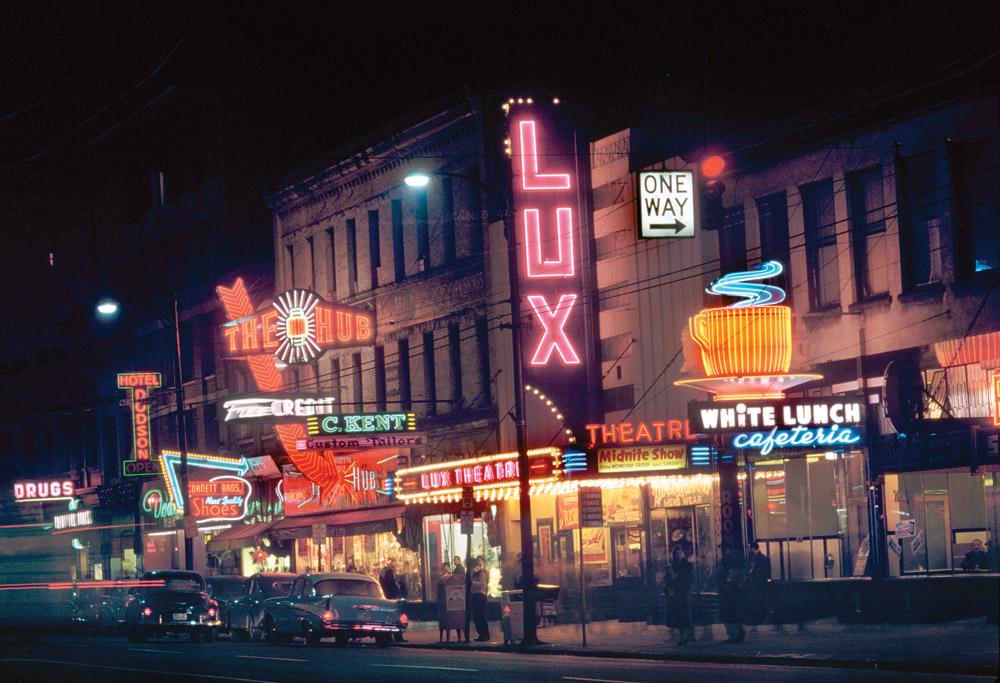

Fred Herzog Hub & Lux 1958 Courtesy Equinox Gallery

Fred Herzog Hub & Lux 1958 Courtesy Equinox Gallery

Fred Herzog Orange Cars Powell 1973 Courtesy Equinox Gallery

Fred Herzog Orange Cars Powell 1973 Courtesy Equinox Gallery

Fred Herzog in Vancouver, September 2012 / photo Hubert Kang

Fred Herzog in Vancouver, September 2012 / photo Hubert Kang

Fred Herzog Main Barber 1968 Courtesy Equinox Gallery

Fred Herzog Main Barber 1968 Courtesy Equinox Gallery