Generously supported by RBC

How do artists contemplate the future? Here, 10 Canadian artists with forward-thinking practices that use biosensor data, airbrushing, geocaching, 18th-century newspapers and more. These practices signal possible ways ahead, but also reflect on the past, and the present.

Annie MacDonell, The Fortune Teller, 2015. HD video, 12 minutes.

Annie MacDonell, The Fortune Teller, 2015. HD video, 12 minutes.

Annie MacDonell

In Annie MacDonell’s 2015 film The Fortune Teller, recently exhibited at London’s McIntosh Gallery, the meticulous repair of a cast-resin hand belonging to a penny-arcade fortune teller soon becomes a continuous age-old loop of the hand-object, and its varied gestures.

“I had the idea that by reactivating the hand, it would become a portal through which past, present and future could be made to merge and collapse,” explains the Toronto-based artist of the film’s intent, which could also read as an artist’s statement on her photography and film work. Appropriation—like the choreographic restaging of passive political resistance in Holding Still // Holding Together, her multi-channel video installation that debuted at the 2016 Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival—is a means of re-circulating images, and ultimately, narratives.

“We’re all telling the same stories over and over again, even while the language and the forms continue to change,” says MacDonell, who made the Ontario longlist for the 2016 Sobey Art Award. “For me, appropriating and re-animating existing images is an acknowledgement of the continuity of experience, even through all the wild and seismic shifts of history.”

Jay Mosher, Untitled, 2016. Bronze-cast mangrove leaf, zip-tie, aluminum and zinc anode, 61 x 8 cm. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Jay Mosher, Untitled, 2016. Bronze-cast mangrove leaf, zip-tie, aluminum and zinc anode, 61 x 8 cm. Photo: Blaine Campbell.

Jay Mosher

An artist’s day job always has a way of influencing their work. For Jay Mosher, the couple of months he spends out in Fort McMurray handling inspections for oil and gas companies inform excess salt filtered from brackish water—zip-tied to aluminum and zinc objects that recall “sacrificial anodes,” highly active materials often attached to boats, bridges and pipelines as a means of protecting less active material from corroding.

One of 25 artists selected for the 2017 Alberta Biennial, Mosher recently received a Canada Council for the Arts grant to support research for a work that will see him handling a new, corrosive-resistant material—porcelain—and the oversized decorative parrots popular in Earls restaurants in the 1980s. “It’s talking about the domestication of nature, and this postcolonial idea of fetish through the object of the parrot,” explains Mosher.

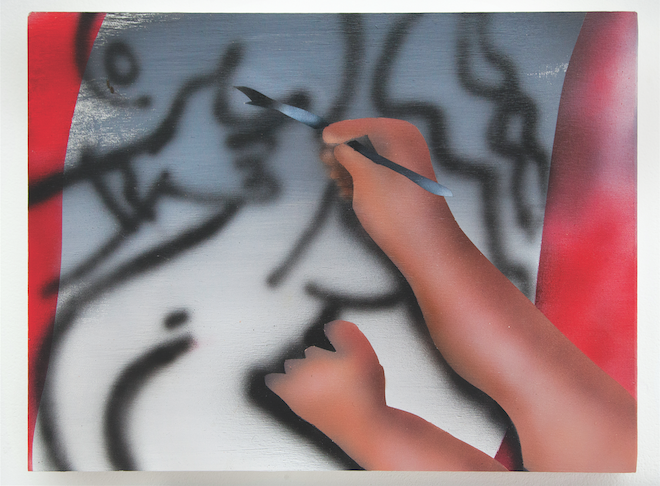

geetha thurairajah, To Keyt, 2016. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 30.5 x 40.6 cm. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

geetha thurairajah, To Keyt, 2016. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 30.5 x 40.6 cm. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

geetha thurairajah

The imagined “third space” in geetha thurairajah’s work alludes to both her inclination toward a post-digital mode of painting, and ambivalence with the expected authentic representation of heritage “otherness.” Born and raised in Waterloo, Ontario, to Sri Lankan parents, the NSCAD-trained artist employs acrylic and airbrush to make flat, deceptively naive images that explore the politics of visibility. A standout work from her 2016 solo show at Toronto’s 8-11 Gallery referenced a sincere fan-art portrait of Canadian rapper Drake.

“I’m interested in partaking in online identity, in the sense that I can completely eliminate my body as a reference,” says the Toronto- and Sackville-based artist, who was nominated for the 2016 RBC Canadian Painting Competition. In fall 2016, a solo show at Toronto’s AC Repair Co. saw a new body of work shifting away from portrayals of naturalism and increasingly inhabiting a specific history of painting.

“The idea of the white male painter entering exotic situations and aestheticizing them really interests me,” she says. “I’ve never been back to Sri Lanka, and I have these othering thoughts about what Sri Lanka can be, so it’s almost like I’m approaching Sri Lanka as if I were an exotic flaneur with a lot of my imagery.

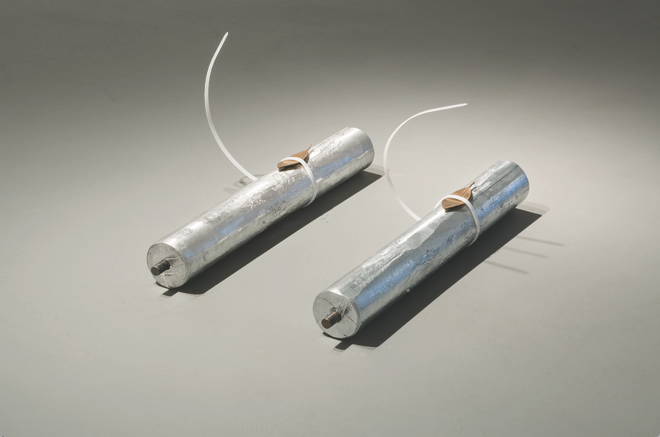

Erin Gee

Since 2012, Erin Gee’s Swarming Emotional Pianos has been transposing biosensor data—think heart rate, sweating and breathing—into biologically harmonic chamber music. The ongoing cybernetic musical performance work converts the heightened neural activities of a participant’s emotions into chime and tubular bell signals that are played by Teensy-powered robots.

“I’m really grasping at what intimacy and empathy is in this work in physical ways, speaking to breakdowns of communication in technological and natural languages alike,” says the Montreal-based artist and composer. Currently an assistant professor in Concordia’s communications department, Gee—who has recently exhibited work at the Dunlop Art Gallery and Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal—is now at work on a VR commission for Trinity Square Video that’s slated to debut in fall 2017.

“I’m aiming to produce a first-person counter-terrorist game that spoofs on the conflation of military action and pop-star celebrity,” she says, now intrigued with what it means to “fake” emotions. “The player drives the performance of a pop star in the war zone through their emotions—as read by my biosensors.”

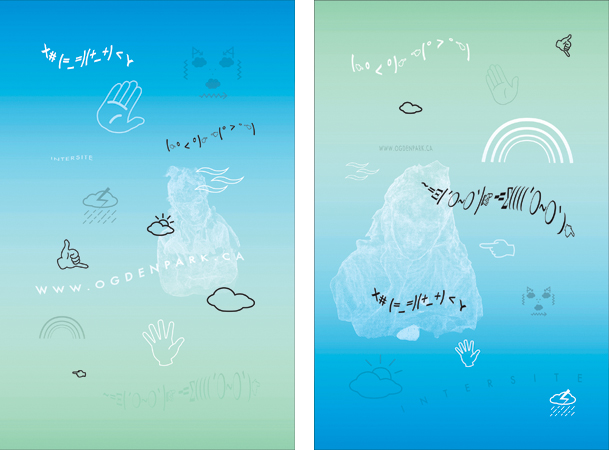

Ella Dawn McGeough and Dustin Wilson, OGDEN PARK: RETREAT!, 2016. Digital images, dimensions variable.

Ella Dawn McGeough and Dustin Wilson, OGDEN PARK: RETREAT!, 2016. Digital images, dimensions variable.

Ella Dawn McGeough

Ella Dawn McGeough was six years old when she met Frank Ogden: it was 1988, and the Vancouver-born artist’s encounter with the Canadian futurist took place on his Coal Harbour–anchored houseboat, back when he had partnered with her older brother on a fax-delivered news service. Better known as Dr. Tomorrow, Ogden was among the first to foresee the Internet’s hold on our daily lives, which were later packaged as 40 predictive laws.

“He was working at the crest of New Age mysticism, the dawn of the Internet, and neoliberal corporate culture—a wave that continues to crash with increasing intensity,” explains McGeough. Alongside Conceptual artist Dustin Wilson, a fellow 2013 graduate from the University of Guelph’s MFA program, McGeough formed, in 2014, Friends of Ogden Park. The collaborative project uses Ogden’s laws as the basis for real and virtual art objects and performative game-centred activities.

In November 2016, OGDEN PARK: RETREAT! took place at Calgary’s Intersite festival, skewering the so-called technological singularity with corporate-style motivational PowerPoint presentations and “geo-caching” relays across the festival’s different venues. “We want the work we do through Friends of Ogden Park to offer a humanistic and materially driven counterweight to the instrumental pragmatism of Ogden’s Laws.”

Hannah Doerksen, Worn Out with Exhaustion by This Unending Chain of Experiments, 2015. Mixed media, digital projection and musical score composed and performed by Andrea Neumann with Catherine Thompson and the CIM choir, dimensions variable. Courtesy Pilot Projects, Philadelphia. Photo: Andrew Pinkham.

Hannah Doerksen, Worn Out with Exhaustion by This Unending Chain of Experiments, 2015. Mixed media, digital projection and musical score composed and performed by Andrea Neumann with Catherine Thompson and the CIM choir, dimensions variable. Courtesy Pilot Projects, Philadelphia. Photo: Andrew Pinkham.

Hannah Doerksen

Funeral homes, hotel lobbies, waiting rooms and deserted shopping malls: these are all the artificial spaces Hannah Doerksen evokes in her work, specifically for their stuck-in-a-rut ambience. “A lot of them are about feeling stuck,” says the Calgary-based artist, whose work has shown at the Esker Foundation’s Project Space and Banff’s Walter Phillips Gallery. “Stuck in time or stuck in an apathetic view for the future tied to the hope that there is something that could be reached that would be better.”

For her December 2016 Art Gallery of Alberta solo exhibition, the failed optimistic future of an abandoned mall becomes an emotional imaginative space to channel ghosts of the past. Alongside faux-marble neoclassical statues, silk floral vase arrangements and a looping video work of the artist engaged in banal, narcissistic reflections on her life, the work touches on the vacancies of the self, especially at a time when loneliness and solitude have become rare commodities in our increasingly connected world.

“You’re always expected to be reachable, but there’s a physical distance now,” says Doerksen, who was included in a two-person show last June at Philadelphia’s Pilot Projects. “You don’t necessarily have the closeness, the shared physical space. It’s now a conceptual space, and I’m interested in how that produces a different kind of isolation.”

Ruth Marsh, Bee Taxidermy 28, 2011. Bee, discarded jewellery parts, aluminum drink can, discarded electronics, glass and wood, 6.4 x 5 x 5 cm. Photo: Christina Arsenault.

Ruth Marsh, Bee Taxidermy 28, 2011. Bee, discarded jewellery parts, aluminum drink can, discarded electronics, glass and wood, 6.4 x 5 x 5 cm. Photo: Christina Arsenault.

Ruth Marsh

For the past few years, Ruth Marsh has been receiving packages of found, dead bees. The mailed submissions that arrive at her Halifax studio come from across the country, and have resulted in a collection of more than 500 bees. So far, Marsh has painstakingly built 300 individual bees, using discarded jewellery, electronics and computer parts to create the “hybrid bionic honeybees” at the centre of “Ideal Bounds,” her 2016 solo exhibition at Sackville’s Struts Gallery.

Since then, the show—set in the near future of 2050, where these first prototypes of the now extinct bee species are presented as pseudo-scientific museum artifacts, and even come alive through stop-motion animation—toured to Calgary’s New Gallery and North Bay’s White Water Gallery.

“All my work, really, has to deal with a meditative, repetitive process,” explains the community-engaged multidisciplinary artist, who has a solo show of drawings at Halifax’s Craig Gallery opening February 2017. “It’s the idea of effort being kind of like a loving practice, and putting so much time, intention and repetition into a poetic approach toward dealing with environmental issues.”

Ben Schumacher, New York City Farm Tower: Peter Friel, Rochelle Goldberg, Jason Matthew Lee, Michael Pollard, Jared Madere, Andy Schumacher, Lillian Paige Walton, Jonathan Gean, Eric Schmid, Jonas Asher, Rachelle Rahme, Lauren Burns-Coady, Elaine Cameron Weir, Jenny Cheng, and Heinrike Klinger, 2015. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Courtesy Bortolami Gallery, New York.

Ben Schumacher, New York City Farm Tower: Peter Friel, Rochelle Goldberg, Jason Matthew Lee, Michael Pollard, Jared Madere, Andy Schumacher, Lillian Paige Walton, Jonathan Gean, Eric Schmid, Jonas Asher, Rachelle Rahme, Lauren Burns-Coady, Elaine Cameron Weir, Jenny Cheng, and Heinrike Klinger, 2015. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Courtesy Bortolami Gallery, New York.

Ben Schumacher

When Ben Schumacher was growing up in Kitchener, Ontario, the region’s Mennonite culture had more of an impact on his practice than its now touted “Silicon Valley North” status. Which makes sense, since the group’s rejection of modern technologies portends Schumacher’s critical concern with the collection and manipulation of data to generate autopoietic structures.

For his second solo show at New York’s Bortolami Gallery in 2015, the now New York–based artist—he received his MFA at New York University four years earlier—used architecture, sculpture, 3-D printed objects, radio transmissions and even sun cults to create the staging for an architecture competition soliciting designs for a “farm tower” near the High Line. Meanwhile, his sculpture at the Biennale de Montréal features rusted telegraph cables from the bottom of the ocean that had been there for more than a century, and is part of an ongoing project exploring the history of underwater telecommunication infrastructures.

“The history of the cables dates to the 1800s. The technology is basically the same as it was at that time for moving information around the world and connecting people,” he explains. “The work I am trying to do is making this deep connection to human relationships in general.”

Pinnguaq Productions,Virtual-reality trailer for Bang Bang Baby , 2014. 360-degree video, 2 minutes 45 seconds. Courtesy Scythia Films.

Pinnguaq Productions,Virtual-reality trailer for Bang Bang Baby , 2014. 360-degree video, 2 minutes 45 seconds. Courtesy Scythia Films.

Nyla Innuksuk

Nyla Innuksuk’s first virtual-reality experience was only two years ago, watching 360-degree videos on Google Cardboard. Now a partner with Pinnguaq, a tech startup with offices in Nunavut, British Columbia and Ontario, the Igloolik-born VR-content creator and filmmaker is considered a leader in a rapidly growing field. She is collaborating with artists like Tanya Tagaq and A Tribe Called Red on immersive projects, and was a recent resident in Open Immersion, an experimental VR-documentary lab designed by the National Film Board of Canada and the Canadian Film Centre.

She’s also one of the architects behind the joint VR commissioning project 2167. Co-presented by Concordia University’s Initiative for Indigenous Futures, TIFF, imagineNATIVE and Pinnguaq, the sesquicentennial initiative invited six Indigenous filmmakers and artists—including Kent Monkman and the Postcommodity collective—to imagine Indigenous culture 150 years into the future. Innuksuk will be producing the works, as well as overseeing the project’s technical elements. She’s proud of the possibilities that 360-degree VR filmmaking brings to her community: “Indigenous people are natural storytellers. There are a lot of really great young artists who are coming forward in different mediums and giving a contemporary twist to their stories and cultures.”

Camille Turner (with Ayoka Junaid), Afronautic Research Lab , 2016. Documentation of performance/installation at the A.C. Hunter Public Library Arts and Culture Centre, St. John’s. Photo: Sandra Brewster.

Camille Turner (with Ayoka Junaid), Afronautic Research Lab , 2016. Documentation of performance/installation at the A.C. Hunter Public Library Arts and Culture Centre, St. John’s. Photo: Sandra Brewster.

Camille Turner

This September, the Afronauts—descendants of West Africa’s Dogon people, who left Earth 10,000 years ago only to return to save the planet—touched down in their brown Pierre Cardin–esque capes at St. John’s A.C. Hunter Library Arts and Culture Centre to set up their Research Lab. As part of Eastern Edge Gallery’s “New-Found-Lands” group show, Camille Turner encouraged locals to sift through 18th-century newspapers featuring classified ads placed by Canadian slave-owners.

The performance and installation is an ongoing project intertwined with Turner’s four-year excavation of Canada’s hidden history of slavery. Previously, she had mined this research for her Miss Canadiana heritage walking tours, and this research has deepened since she started her PhD last fall in York University’s environmental-studies program.

“I often feel like what I am doing is science fiction,” says the Kingston, Jamaica–born, Toronto-based media and performance artist, who was recently highlighted in Johanna Householder and Tanya Mars’s follow-up to their Canadian women in performance art anthology. “You know, to cavort with the ghosts is what I think about, because these things haunt the present, and sci-fi is a great language for connecting with the ghosts.”

This post is adapted from the feature article “Up Next,” generously supported by RBC in the Winter 2017 issue of Canadian Art. To get every issue of our magazine delivered to your door before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.

Erin Gee, Swarming Emotional Pianos, 2016. Aluminum tubes, Teensy-based robotics, iRobot Create, hanging video projection and stereo sound. Courtesy Hamilton Artists Inc. Photo: Caitlin Sutherland.

Erin Gee, Swarming Emotional Pianos, 2016. Aluminum tubes, Teensy-based robotics, iRobot Create, hanging video projection and stereo sound. Courtesy Hamilton Artists Inc. Photo: Caitlin Sutherland.