Since I’ve met him, artist Bennie Allain has been working in New Brunswick: first in Sackville, and now in Fredericton. He tells me—a Vancouver-trained, Fredericton-based artist—about growing up in rural PEI, in amongst an enormous extended family, and talks about reconciling 1960s film footage of the Beatles with family photos from the same years, which depict scenes of self-sufficient agriculture, and houses without electricity or television. He talks about blue-collar culture in small communities that have been driven for generations by industrial agriculture, fisheries and shipyards.

My experience of the economic inequalities Bennie describes has always been incidental, anecdotal or inferred, but his prolific painting practice touches on them again and again, with morbid fascination. “I don’t know a lot about politics…” Bennie says, but his work gives voice to a disquiet that our community of artists holds in common. There’s humour and critique in his work. There’s big people stepping on little people. There’s blindfolded figures, vulgar, bodily things and the blank stares of people who’ve been ground down, navigating narratives of inevitability.

Now, as I comb the Internet looking to provide some concrete context for his work, I am coming up empty-handed. How do you talk about a palpable feeling of distrust and despair? One that is evoked by JPEG and IRL images of ill-kept buildings and aging infrastructure, as much as by the rampant anxieties of what my friends describe as “debt slavery”?

I can tell you that the corporation that (together with its subsidiaries) controls entire supply chains for major industries in New Brunswick—like forestry, and oil and gas—also owns all of the newspapers in the province. You may make of that what you will, but Bennie’s recent series of paintings titled East Coast Horrorshow critiques this control quite explicitly. One article I read says that New Brunswick has had the highest out-migration in the country and the lowest median income: $10,000 per year below the national average, and $30,000 below the median income in Alberta.

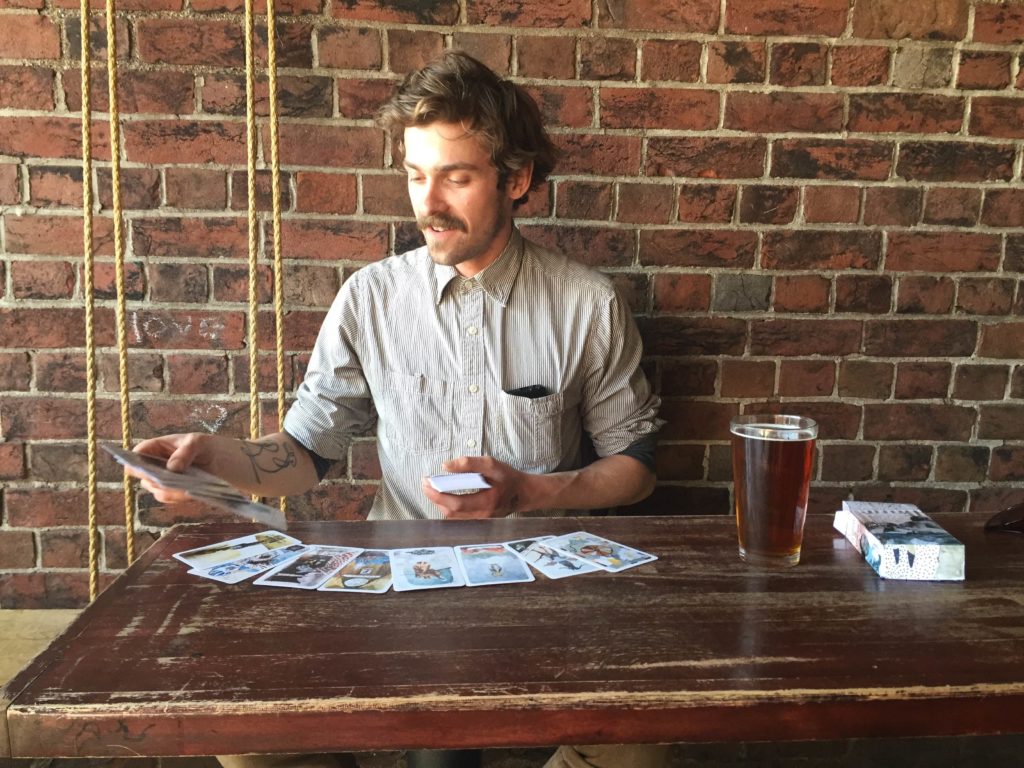

Double-edged—like the images in the tarot deck Bennie recently created, a series of 78 paintings cautiously described as “Cards of Fortune”—the economic and cultural inheritances in this province do make other things possible.

A ninja turtle, Tim Horton’s coffee and Pope Francis are just some of the images pictured in New Brunswick artist Bennie Allain’s tarot deck. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

A ninja turtle, Tim Horton’s coffee and Pope Francis are just some of the images pictured in New Brunswick artist Bennie Allain’s tarot deck. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

The people I know here have a lot of time and space to make work, and no shortage of complicated histories and experiences to make work about. They are making art, playing in bands, recording podcasts, growing and gathering food and using grassroots organizing strategies to create cultural space.

These forms of creative life in New Brunswick remind me of something I read in a Sarah Lucas catalogue, about how art wasn’t something that could be taken away from her by depriving her of money or materials.

And I’m reminded of the early artist-run histories I was steeped in when doing my BFA at UBC. There’s a spirit of artist-run self-determination that I really like out here. A collaborative and irreverent attitude. A sense of humour.

Bennie’s practice makes good use of this supportive, interdisciplinary community. He’s basically taken on art direction for the Fredericton band Cellarghost, whose music articulates the agitated disillusionment I also see in Bennie’s art, and he’s working with other artists at shiftwork, a studio collective in downtown Fredericton.

Bennie Allain in his Fredericton studio with some of his “Cards of Fortune” paintings, often created with cast-off acrylics purchased at the Salvation Army Thrift Store—a supply that reflects economic challenges many artists face in the province, as well as artistic freedoms. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

Bennie Allain in his Fredericton studio with some of his “Cards of Fortune” paintings, often created with cast-off acrylics purchased at the Salvation Army Thrift Store—a supply that reflects economic challenges many artists face in the province, as well as artistic freedoms. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

We were both working on site-specific work for Flourish, a new festival happening in the city, when Bennie made a thoughtful comment about how the colours and patterns I was using in my work were very grandma’s house: pale pinks and greens and floral bedsheets.

I’d say Bennie’s palette is similarly out-of-date, though more of a grandpa variety: browns, deep navy blues, sky blues, burgundy, ochre, polka dots, plaids and stripes. His colours are always mixed from the materials readily at hand: usually small bottles of crafters’ acrylic paints bought at the Salvation Army Thrift Store, though sometimes he finds oils and expensive art paper, and then will start working with those. The photos embedded in the work are cut from second-hand magazines and books of similar origins.

When I look at Bennie’s paintings, there’s the flotsam feeling of complex architectures being broken apart and washed ashore—but there’s also a continuity in structure, gesture, line-quality that keeps all of the works in close conversation with each other.

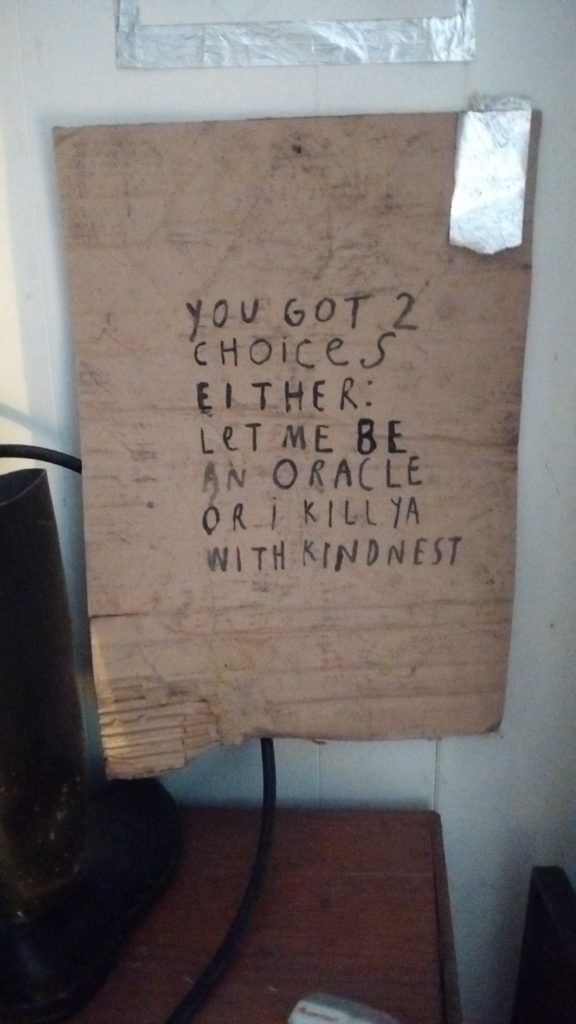

There’s always a joke, a play between the words and the images, and the text that he uses to annotate each picture plane puts forward the imagined possibility that these are so many panels in an absurd and non-linear graphic novel: an unusual compendium of psychological struggle and social critique.

Animal figures from the ancient Greeks’ zodiac lapse into erotic human-animal unions and monstrous hybrid creatures, populating a strange world that’s also inhabited by the ghosts of European settlers, prospectors and Victorian school children, by Judge Judy and Pope Francis, by Ninja Turtles and hockey players and politicians: all of them moving through bleak landscapes of lakes and snow and mud and sky; trees and hills and fields filled with grains and withered grasses; houses and kitchen tables and endless cups of Tim Horton’s coffee.

Bennie cites David Hockney, Egon Schiele and Jon Claytor as being formative to his interests while doing his BFA at Mount Allison, but he also cites Black Flag and Alice Cooper.

Fredericton artist Bennie Allain spreads his “Cards of Fortune” tarot deck, which includes Judge Judy on the “Justice” card. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

Fredericton artist Bennie Allain spreads his “Cards of Fortune” tarot deck, which includes Judge Judy on the “Justice” card. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

Two years ago, Bennie was sharing space with Vancouver artist Heidi Nagtegaal as part of her long-standing Hammock Residency project. She gifted him his first tarot-card reading, setting him on a path towards the formulation of his new deck.

When Bennie met Heidi, she was in the midst of living 17 consecutive months outside of a monetary economy; but when I meet her, it’s on lunch break from her day job at Homestead Junction in Vancouver, while I’m in town visiting family. She laughs as she describes him to me: standing at the stove wearing a bow tie, always offering her a morning greeting, a cup of coffee and some small, prodding joke.

Enamoured with a cigarette-rolling machine someone had given her as a gift, Bennie started leaving a dart out for Heidi, each time he rolled a cigarette for himself. There were cigarettes all over the apartment: tucked in the hammock, placed on the kitchen table, resting on the arms of a chair… He started writing her name on them, so that she’d know they were hers.

I’ve bought and brought one of his tarot decks with me on this trip back to BC, and Heidi uses them to give me my first tarot reading.

A painting in Bennie Allain’s Fredericton studio. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

A painting in Bennie Allain’s Fredericton studio. Photo: sophia bartholomew.

“If your intent is to find meaning, then you’ll find meaning,” Bennie had said to me back in Fredericton when we were talking about the cards, though I imagine there is quite a bit more to it than that… I gift this deck to Heidi, and it feels like we’ve made a nice circle. I think of Fluxus artist Robert Filliou and his articulation of the Eternal Network. “Art is what makes life more interesting than art.” I think Robert Filliou said that, too.

I think about grandma’s house and grandpa’s palettes. I think about that heady combination of despairing distrust and DIY determination. I think about how a fortune isn’t the same as a future, and as I start shuffling the cards again, I keep thinking.

sophia bartholomew is an artist based in New Brunswick who works with performance, language, and other time-based media. She co-directed Connexion Artist-Run Centre in Fredericton from 2012 to 2015 after finishing her BFA at UBC.

This article is part of Canadian Art’s year-long Spotlight on New Brunswick series, created with the support of the Sheila Hugh Mackay Foundation.